Bankers in Hong Kong and Singapore are in for a few busy months financing a rush of shipments from Asian exporters into the US ahead of President-elect Donald Trump's proposed tariffs. But once those import taxes kick in, there is only one group that might fill the hole in banking revenue: the wealthy.

Historically, lenders that make their profits in Asia have relied heavily on cross-border commerce: HSBC Holdings Plc facilitated $850 billion of it last year. Open, rules-based exchange of goods is a “lynchpin of global economic growth,” José Viñals, chairman of Standard Chartered Plc, told shareholders in the bank's latest annual report. StanChart garnered an income of $6.9 billion in 2023 from its corporate, commercial and institutional banking network, compared with $4.6 billion from affluent clients. The bulk of DBS Group Holdings Ltd.'s 2% loan growth in the first nine months of this year came from trade.

Trump's proposed 10% to 20% tariff on all foreign-made goods — 60% or higher on products from China — will be more than a bucketful of sand in the wheels of commerce. Anxiety is running high. Out of the top 15 trade partners with whom the US has a trade deficit, eight (1) are from Asia. “The entire region is in the firing line,” according to Priyanka Kishore, an economist at Singapore-based consulting firm Asia Decoded Pte.

And yet, even with the knock-on effects of trade on domestic demand, and a slowdown in other loans such as mortgages, Trump is unlikely to be a disaster for the region's banks. They may be able to tap some new levers. For a start, the likes of HSBC, StanChart and DBS may be able to make up for some of the lost opportunity for financing by pricing their loans at a comfortable premium.

Trump's policies, including tax cuts and tariffs, may trigger faster inflation, which could restrain the Federal Reserve's interest rate reductions and set a floor for margins in Hong Kong's banking market. However, the flip side may be that the much-awaited recovery in the city's commercial real-estate from lower borrowing costs may fall short, according to Bloomberg Intelligence.

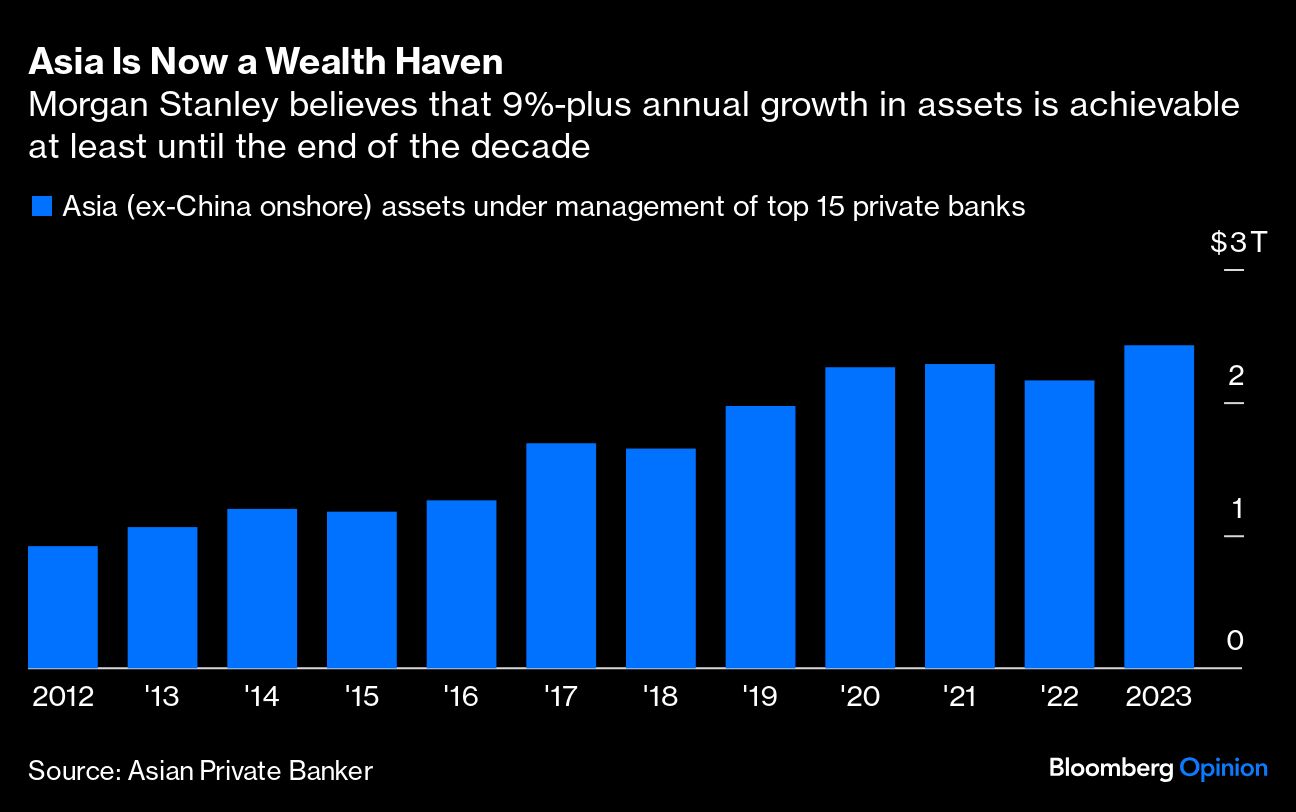

That brings us to a bigger point: Banks should perhaps look beyond balance sheet expansion, especially if China's stimulus doesn't stoke intra-Asian trade. Wealth management and capital markets could shape up as the new battleground. In 2016, when Trump was first elected president, assets under management at the top 15 private banks in Asia (excluding onshore Chinese wealth) was $1.3 trillion. Now it's nearly double of that. A similar pace of growth until at least the end of the decade is achievable, Morgan Stanley says.

There are several ways to serve the affluent. By offering tax breaks on a range of assets, Hong Kong and Singapore have enhanced their appeal as preferred locations to set up family offices. Last year, each city managed $1.3 trillion in offshore assets, next only to Switzerland's $2.5 trillion.

Asian billionaires have been at the forefront of growth. They will be in pole position in the coming years, too: In countries like China, India and Indonesia, trillions of dollars are set to change hands from one generation of ultra-high-net-worth tycoons to the next, with family offices facilitating the division. This money will have company. “We expect increased wealth flows from Europe and North America as many global investors see Asia–Pacific as a third safe haven for portfolio diversification,” McKinsey & Co. noted in a recent report.

Momentum is starting to build. Bank of Singapore, which is Oversea-Chinese Banking Corp.'s private bank, plans to capture more asset flows from wealthy people in the UK as the Labour Party government contemplates raising taxes on foreign residents in the country. The trick, however, is to be circumspect about which family offices to sign up. Clients who trade rarely and don't like paying fees can become margin traps.

Tax policy in the US, too, will be watched keenly by Asian bankers. By winning control of the US Senate, the Republicans have dealt a blow to Democrats' hope of shifting the burden of Trump's 2017 tax cuts — which expire end of next year — toward corporations and rich individuals.

If inflation is high and asset prices volatile, the global wealthy will want to put their cash to work in unconventional assets, especially ones they think will do well during Trump's second term. Bitcoin's rally to within striking distance of $90,000 shows that amply.

This, too, is an area where Singapore and Hong Kong banks are expanding services for their rich clients. Looks like they're well prepared for a world in which goods movement is riddled with friction — but the wheels of wealth creation are better greased than ever.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Andy Mukherjee is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering industrial companies and financial services in Asia. Previously, he worked for Reuters, the Straits Times and Bloomberg News.

(1) China, Vietnam, Japan, South Korea, India, Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia

Essential Business Intelligence, Continuous LIVE TV, Sharp Market Insights, Practical Personal Finance Advice and Latest Stories — On NDTV Profit.