(Bloomberg Opinion) -- A row is brewing for control of Japan's everything app.

Elon Musk might talk about building an all-encompassing app. Japan already has one. Having evolved from a WhatsApp-like messenger into a product that touches almost every aspect of society, Line is now at the center of a tug-of-war for control — and risks becoming the latest powder keg that threatens relations between Japan and neighboring South Korea.

Line was created by the Japanese unit of South Korea's internet giant Naver Corp., which still holds 50% of it in a complex structure overseen by SoftBank Group Corp. But after a series of cyberattacks last year spooked Japanese regulators, discussions have begun about divesting Naver's holdings and moving control of the service fully within Japan's borders.

With typical bombast, opposition politicians in South Korea have likened the move to a new annexation of the country, accusing Japan of seeking to “pillage our cyber-territory,” and President Yoon Suk Yeol of kowtowing to its former colonizer.

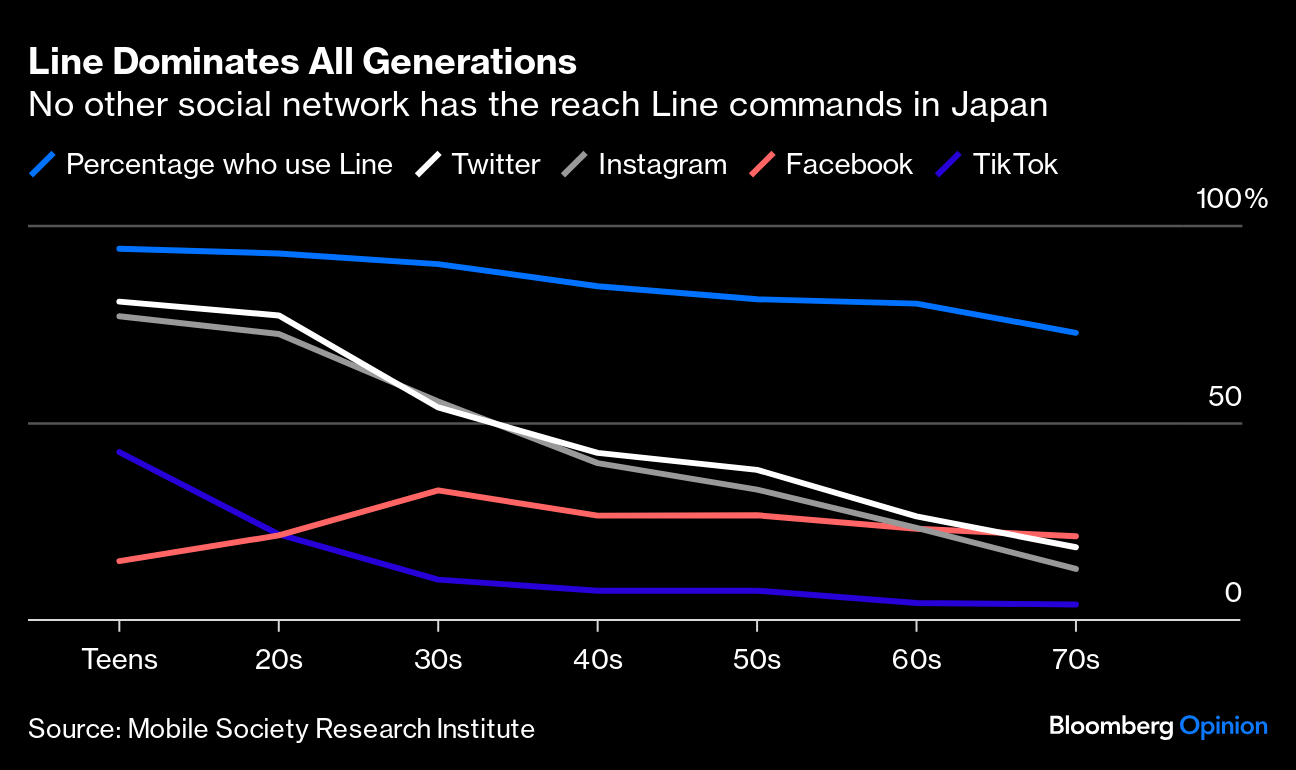

Line is inescapable. Like any messaging app, you can use it to text friends, call your grandma or video-conference your boss. But its influence is much broader: You can buy lunch at the 7-Eleven, book a doctor's appointment, find a part-time job or send your mother-in-law a gift. More than 80% of the population under the age of 80 use it, including a stunning 95% of teenagers — more than any other social network.

Like Musk's X, which counts Japan as its second-largest market, Line traces its success to the aftermath of the March 11, 2011 earthquake and tsunami. The disaster, which killed nearly 20,000 people and wrecked a nuclear power plant, also collapsed mobile networks, leaving millions unable to contact friends and family.

Employees at Naver's Japan unit were able to communicate using KakaoTalk, which rival Kakao Corp. had launched a year earlier. But there was no equivalent yet popular in Japan: Naver engineer Shin Jung-ho, who would become known as the “father of Line,” eventually confirmed his wife's safety through MSN Messenger, according to journalist Takashi Sugimoto's book .

Spun up and introduced within months, the service quickly became a hit amid a broader transition to smartphones. Its trademark cutesy reaction stickers followed shortly, long before competitors supported GIFs or Memoji, and forever changed how the country communicated. Though global domination never materialized, Japan, Taiwan and some other Asian markets have been in its thrall ever since.

Line went public in 2016, but its ownership has gradually become more complex. SoftBank led a takeover in 2019, aiming to combine Line with its stable of brands including cashless payment leader PayPay and news portal Yahoo Japan.

But Naver maintained part control, holding 50/50 ownership with SoftBank of A Holdings, majority owner of the combined Line-Yahoo-PayPay firm now known as LY Corp. There's surefire potential to combine Line's reach with the lucrative payment, trading, banking and insurance arms of PayPay into a WeChat-style service that would eclipse anything in Musk's wildest dreams.

The complex capital makeup and the cross-border nature of Line's business are at the center of the dispute. Japanese regulators have been turning the screws on LY Corp. following the data leaks last year due to issues on Naver's side. SoftBank and the South Korea firm are in talks over its stake, worth nearly $6 billion. Executives at LY have taken moves seen as distancing themselves from Naver, cutting outsourcing ties with the firm, and jettisoning Shin — the last remaining South Korean in top management, and the highest-paid executive in Japan — from the board.

This has raised eyebrows in Seoul. “Having nurtured Line for 13 years, will Naver have control snatched away?” fretted one local headline. The government has expressed its displeasure. Ruling party politicians have called on Yoon to do more. And the opposition has been much more vocal, with Democratic Party of Korea leader Lee Jae-myung among those invoking familiar historical grievances.

In a Facebook post, he drew comparisons between Takeaki Matsumoto, who as communication minister is in charge of regulating Line, and Matsumoto's great-great-grandfather, Hirobumi Ito — as fate would have it, the first prime minister of Japan, who forced the signings of treaties that led to the annexation of Korea in 1910.

It's time for all sides to rein this in. Like other social media platforms, Line has become a victim of its own success — too vital to the functioning of society, and too laden with sensitive data, to be left alone. But Japan has poorly communicated its requests, and it remains unclear how much the government is actually pushing for a sale. With diplomacy between Tokyo and Seoul finally turning a corner, the affair seems an unforced error.

In Seoul, meanwhile, everything must stop being about historical grievances. Japan is entitled to be worried about the data breaches, which Naver acknowledges as its fault. Both countries have far more in common than what divides them, and in a dangerous regional neighborhood the opportunity cost for constantly invoking decades-old concerns is high. (See Japanese support for Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co.'s fabs in Kyushu despite Taiwan's own history as a colony.)

Seoul and Tokyo's relations have a habit of spinning out of control over perceived slights. Yoon and his Japanese counterpart, Fumio Kishida, who discussed the issue at the recent trilateral summit, need to exchange some stickers of their own — perhaps a cutesy animal saying, “call me.”

More From Bloomberg Opinion:

-

Humbled Yoon Must Future-Proof Seoul's Alliances: Gearoid Reidy

-

Elon Musk's Everything App ‘X' Is a Bad Idea: Parmy Olson

-

Rakuten's Hanging On. It Must Consider Hanging Up: Gearoid Reidy

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Gearoid Reidy is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Japan and the Koreas. He previously led the breaking news team in North Asia, and was the Tokyo deputy bureau chief.

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com/opinion

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.

Essential Business Intelligence, Continuous LIVE TV, Sharp Market Insights, Practical Personal Finance Advice and Latest Stories — On NDTV Profit.