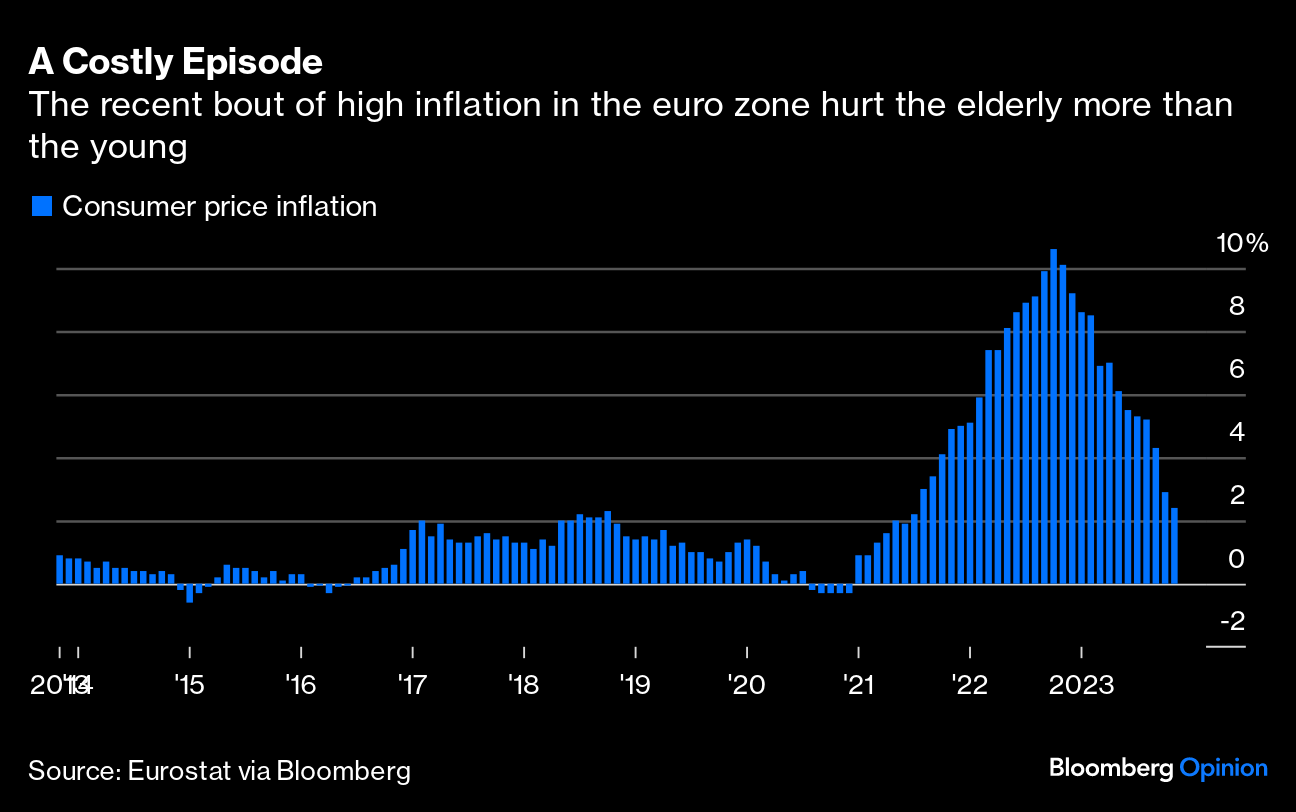

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The unexpected decline of the rate of inflation in the euro zone, to 2.4% from 10.6% a year ago, will limit the strain on European economies and lower the risk that some European voters will opt for demagogic leaders. But it's not all good news. Despite the decrease, this inflation episode reflects the ongoing inability of EU nations to balance the interests of young and old.

As recent research indicates, the recent inflation has been very costly. The 2021-2022 inflation cost more than 3% of national income in France, Germany and Spain, and about 8% of national income in Italy, higher costs than what a typical recession would bring.(1)

It is striking how much those costs fall on the elderly, which is one reason that lowering inflation rates has been such a priority. The elderly usually have the most accumulated savings, and less time to make up for inflationary losses by subsequent compounding. Older people are also more likely to own homes, so face higher home heating bills when energy prices rise. Overall, in the last several years, a low-income retired household in Italy might have taken income cuts of up to 20%, while a middle-aged household in the euro area might have seen a typical income cut of 5%.

During the most recent inflationary episode, neither real estate nor equities served as good inflation hedges. That is in part because a significant part of the inflation was due to energy-price shocks, which lower the value of most assets.

Yet the elderly are by no means the entire story. Not everyone lost from the inflation. Young households in Spain, for instance, gained more than 5% in income. The simplest way a household might gain from inflation is that its debt liabilities decline in real, inflation-adjusted value. On average, the young are more likely to be in debt than the elderly, and own fewer assets. Inflation also tends to lower the value of tenured jobs, such as in academia, and younger people are less likely to hold such posts. The young also tend to have more time in their lives to adjust to negative economic shocks, by for instance geographic or career migration.

Overall, an estimated 30% of the households in the euro area from the inflationary shock. Almost half of 25- to 44-year-olds benefited.

While the existence of so many gainers is good news, it has disturbing implications for the broader European project. Unfortunately, many European polities serve the interests of the elderly more than the interests of the young. Government budgets are allocated to pensions and social security schemes, while innovation and job creation are not prioritized. In general, preservation is valued more than change.

European economies are losing relative status and influence around the globe, and so many of the important achievements of Europe seem to lie in an ever-receding past. Public health measures in Europe often give major benefits to the young, but talented young Europeans tend to migrate to North America more so than vice versa. The rapid disinflation in the euro area is desirable, but it is also yet another way that European polities primarily serve the interests of the old.

To the extent that inflation partially reversed these trends, it was a silver lining in an otherwise a dark macroeconomic time. But it was neither sustainable nor conscious; it's not as if all the major European nations made a conscious decision to support policies that favor the young. In fact, this episode of inflation might induce older voters to revise future policy toward their interests all the more.

The late economist Mancur Olson famously postulated that societies become sclerotic unless they somehow shake up their elites and loosen the grip of their dominant interest groups. He suggested that Japan and Germany grew so rapidly after the Second World War in part because they lost. Despite considerable political upheaval and uncertainty in many European nations — and elsewhere in the world — there are today no disruptions in governance comparable to those the world saw eight decades ago. The return of lower inflation rates to the euro zone indicates that this brief experiment in “remixing the elites” is over.

Unless Europe does more to improve the basic prospects of its young workers and entrepreneurs, fiscal problems and economic growth problems will accelerate. The next time around, inflation rates may be higher yet.

Elsewhere in Bloomberg Opinion:

- Disinflation Will Hasten Rate Cuts From the ECB: Marcus Ashworth

- Coming Down Inflation Is No Walk on Table Mountain: John Authers

- Sorry, European Banks, Investors Just Aren't Into You: Paul J. Davies

Want more Bloomberg Opinion? Subscribe to our newsletter .

(1) The higher inflation costs for Italy stem from a 20% inflation rate, which in turn came from a lack of energy independence, as part of the inflation was transmitted through an energy price shock. That should strengthen the case for renewable energy sources and nuclear power.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Tyler Cowen is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist, a professor of economics at George Mason University and host of the Marginal Revolution blog.

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com/opinion

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.

Essential Business Intelligence, Continuous LIVE TV, Sharp Market Insights, Practical Personal Finance Advice and Latest Stories — On NDTV Profit.