(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Sovereign bond sales are set to increase further next year as budget deficits swell across the developed world. Unfortunately, that coincides with central banks accelerating the reduction of the bond holdings accumulated through quantitative easing. This double whammy means bond yields, particularly at the longer end of the curve, are set for a difficult 2024.

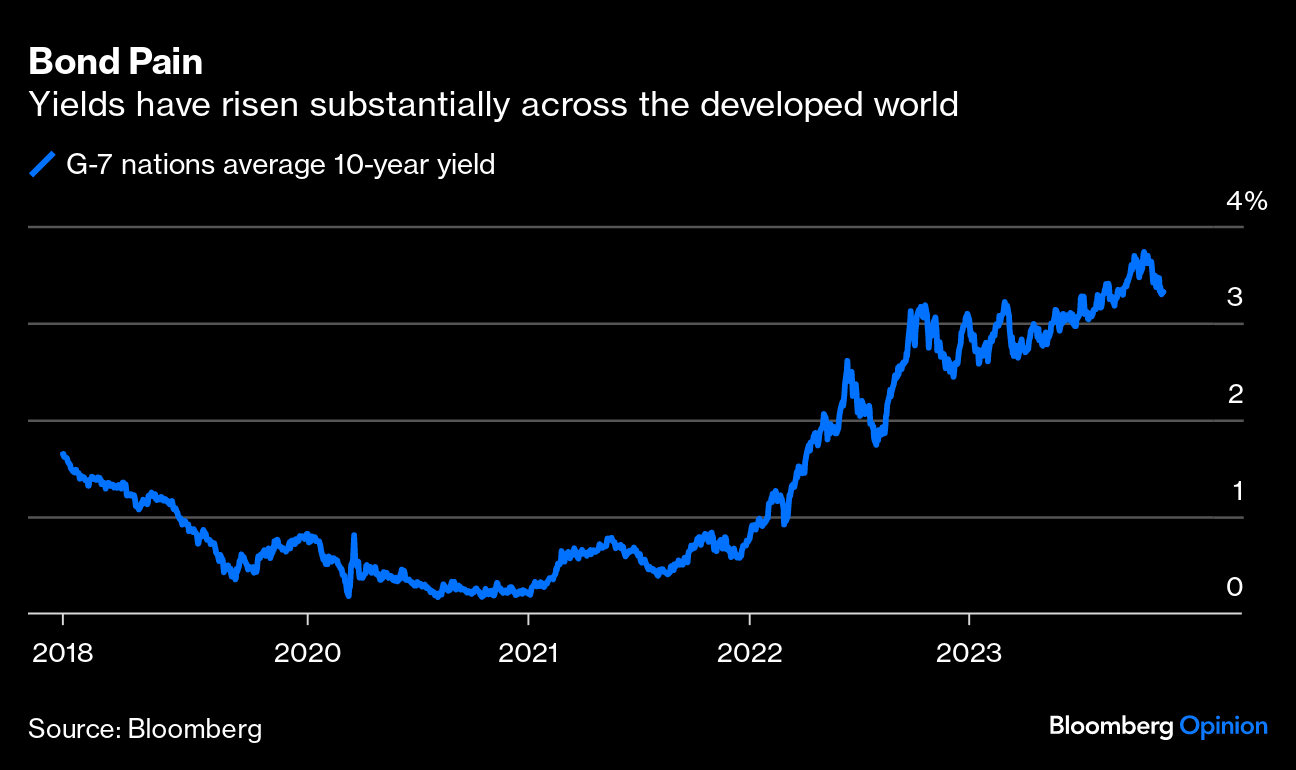

Something may have to give, as investor demand has proven to be decidedly fickle this year. The Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank and the Bank of England may have to curb their enthusiasm for shrinking their balance sheets if government borrowing costs extend the increase that saw the average 10-year yield among Group of Seven nations surge past 3.5% this year, more than double its five-year average.

US Treasury bond issuance is expected to reach a record $1.34 trillion next year, according to analysts at Bank of America Corp. Even that elevated level is barely three-quarters of the projected $1.8 trillion 2024 budget deficit — and BoA expects the 2026 deficit to climb inexorably towards $2 trillion. It's hard to see how bond supply doesn't follow. Relying on foreign investors has proven to be a double-edged sword this past year; if the dollar weakens substantially, it will reduce overseas appetite for Uncle Sam's debt.

The principal driver of the 50 basis-point fall in 10-year US yields so far this month was the lower-than-expected fourth-quarter refunding announcement on Oct. 30. It illustrates how sensitive the US bond market, and by extension the rest of the world, has become to ever-expanding Treasury auctions. Nonetheless, yields at 4.5% remain a full percentage-point higher than they were in April, albeit down from mid-October's 5% peak . Multiple factors affect bond values, but the one constant in an ever-changing world is rising debt issuance.

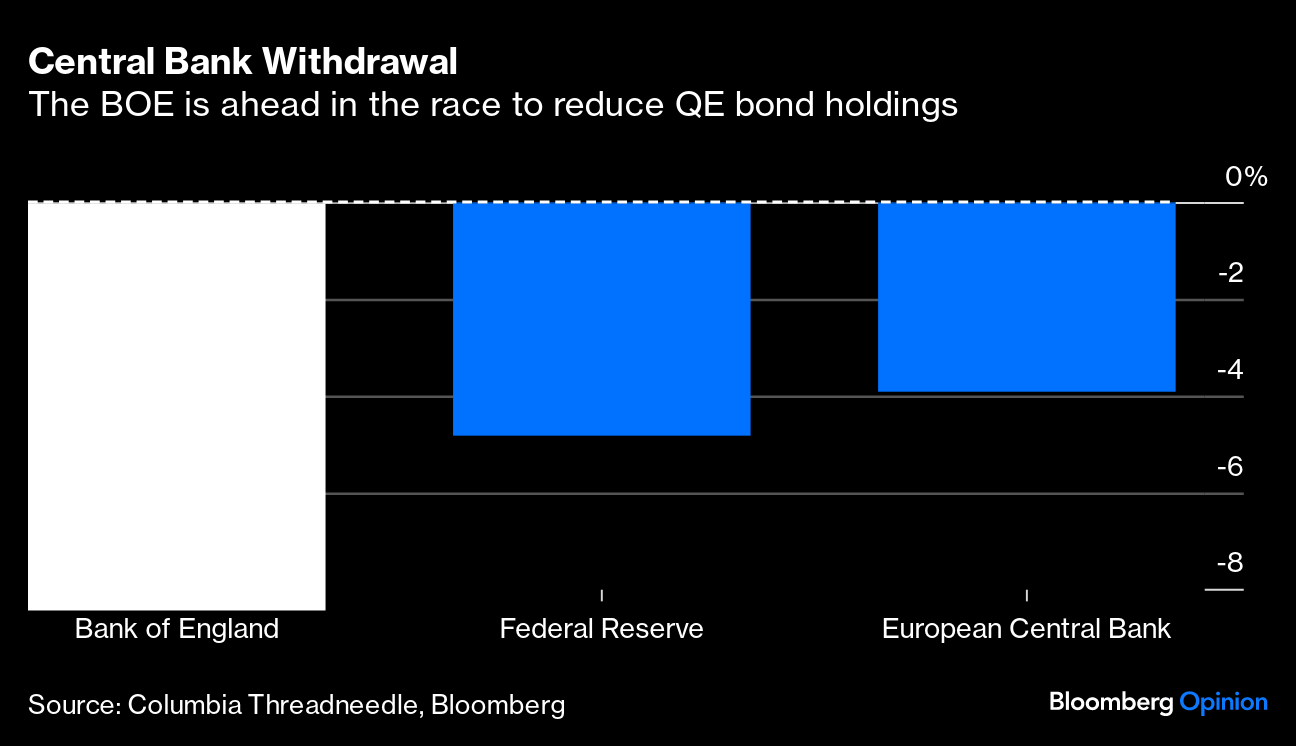

The Fed has been reducing its balance sheet by $95 billion a month since June 2022, and has lopped off a little over a trillion dollars so far to trim it to $7.8 trillion. There's a long way to go to return to the pre-pandemic $4 trillion mark, but maintaining sufficient liquidity in the world's benchmark fixed-income market is paramount. Its reverse repo facility has been fundamental in stabilizing conditions, as market participants can park collateral for ready cash. But its usage is declining rapidly and is now under half its peak. This balancing act has played out well so far, but there's no guarantee this will be sustained. The risk remains that the combination of Fed monetary tightening with expanding US Treasury supply proves deadly.

This picture is mirrored in Europe as Germany, France, Italy and Spain will increase bond sales to more than €1.1 trillion ($1.2 trillion) next year. The European Commission is also expected to issue €150 billion of bonds, an increase of a fifth. Gross sales in the bloc are expected to increase by 10% next year, according to estimates from HSBC Holdings Plc.

But it's the net issuance after redemptions and central bank activity that matters most, especially as ECB support goes into reverse, having started curtailing reinvestments in March on the larger of its twin QE bond pots. Next year the full effect of around €315 billion no longer being pumped back in annually will be felt keenly.

There are hawkish noises emanating from the Governing Council that reinvestments should also be curbed from the second bond portfolio. At the European Banking Congress in Frankfurt last week, Belgian central bank chief Pierre Wunsch called for them to be “stopped as soon as possible.” HSBC's analysts reckon this could come as soon as the Dec. 14 meeting, and project this will add €65 billion to net annual issuance — a 63% increase for the euro region's four biggest borrowers.

Even a small reduction of QE reinvestment looks ill-advised. It's the first line of defense for the euro area as it allows maturing German debt to be recycled into buying Italian bonds. German outflows between June 2022 to September 2023 are €19.2 billion, whereas Italy has enjoyed a €13 billion inflow. Removing that benefit when the euro-area economy is contracting would be foolhardy.

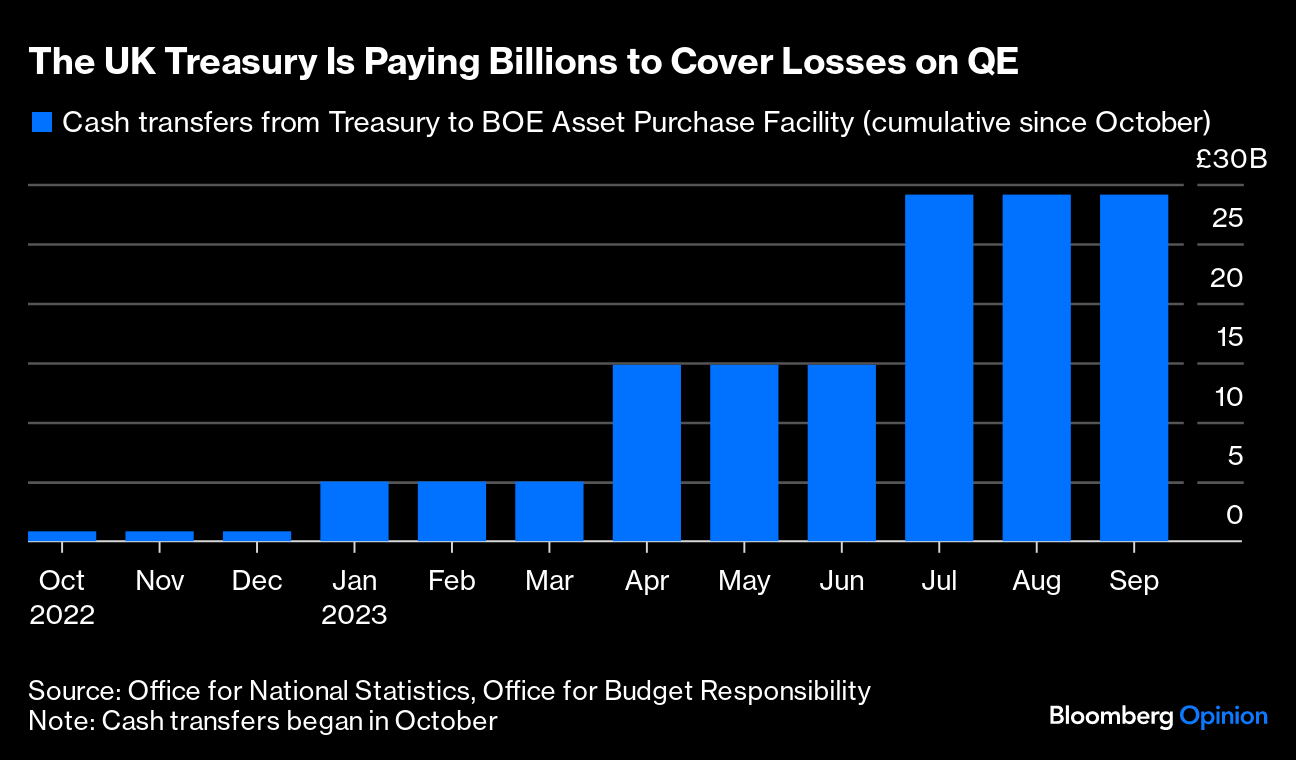

The Bank of England is in a league of its own with quantitative tightening, reducing at double the pace of the Fed and ECB. It's doubling up with active sales back into the market. It will reduce its remaining £750 billion ($930 billion) gilt holdings by a further £110 billion this year.

Despite losses of more than £15 billion so far from active sales, BOE Executive director for Markets Andrew Hauser on Nov 3 made clear that reducing the balance sheet to half its current level is the aim.

UK government bond supply is expected to be around £260 billion next year, a jump of 20% from this year. For the BOE to pile on by adding an extra 40% to the net burden will stretch the tolerance of gilt investors still reeling from the mini-budget crisis a year ago. UK growth, like the euro area, has flatlined for much of the past two years and is on the verge of turning negative.

There's a growing perception that central banks are at the zenith of the interest-rate hiking cycle, but reducing QE bond portfolios would continue to tighten monetary conditions. If global growth slumps next year it might not be long before rate cuts or a pause in balance sheet reduction — or probably both — are on the market's agenda.

More From Bloomberg Opinion:

-

Three Things to Prevent a Treasury Market Meltdown: Bill Dudley

-

How to Make UK Bonds More User Friendly: Marcus Ashworth

-

How America Can Get Its Debt Back Under Control: Karl Smith

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Marcus Ashworth is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering European markets. Previously, he was chief markets strategist for Haitong Securities in London.

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com/opinion

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.

Essential Business Intelligence, Continuous LIVE TV, Sharp Market Insights, Practical Personal Finance Advice and Latest Stories — On NDTV Profit.