NREGA workers have a right to employment on demand, minimum wages, and payment within 15 days. Providing the required funds is a legal obligation.

The recent slowdown of the Indian economy has revived interest in public expenditure on the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act as a means of stimulating demand. Putting money in the hands of the poor, who have a high propensity to consume, is certainly a better-tested means of economic stimulus than corporate tax cuts. Yet, the Indian government blew an estimated Rs 1.45 lakh crore on corporate tax cuts at the first sign of a slowdown a few months ago, without as much as an afterthought for the underprivileged.

The case for enlarging the NREGA budget, however, is not just that it would help to prevent the economy from sliding into the ditch.

The signs of a slowdown in GDP growth are relatively recent, but signs of virtual stagnation in real wages have been around for a long time.

During the first term of the Modi government, the Indian economy was growing at around 7 percent per year in real terms, going by official estimates, but real agricultural wages were barely rising – so much for ‘inclusive growth'. Reviving NREGA could help to give rural workers a fairer share of the growing pie, both by generating public employment and by sustaining higher wages in the private sector.

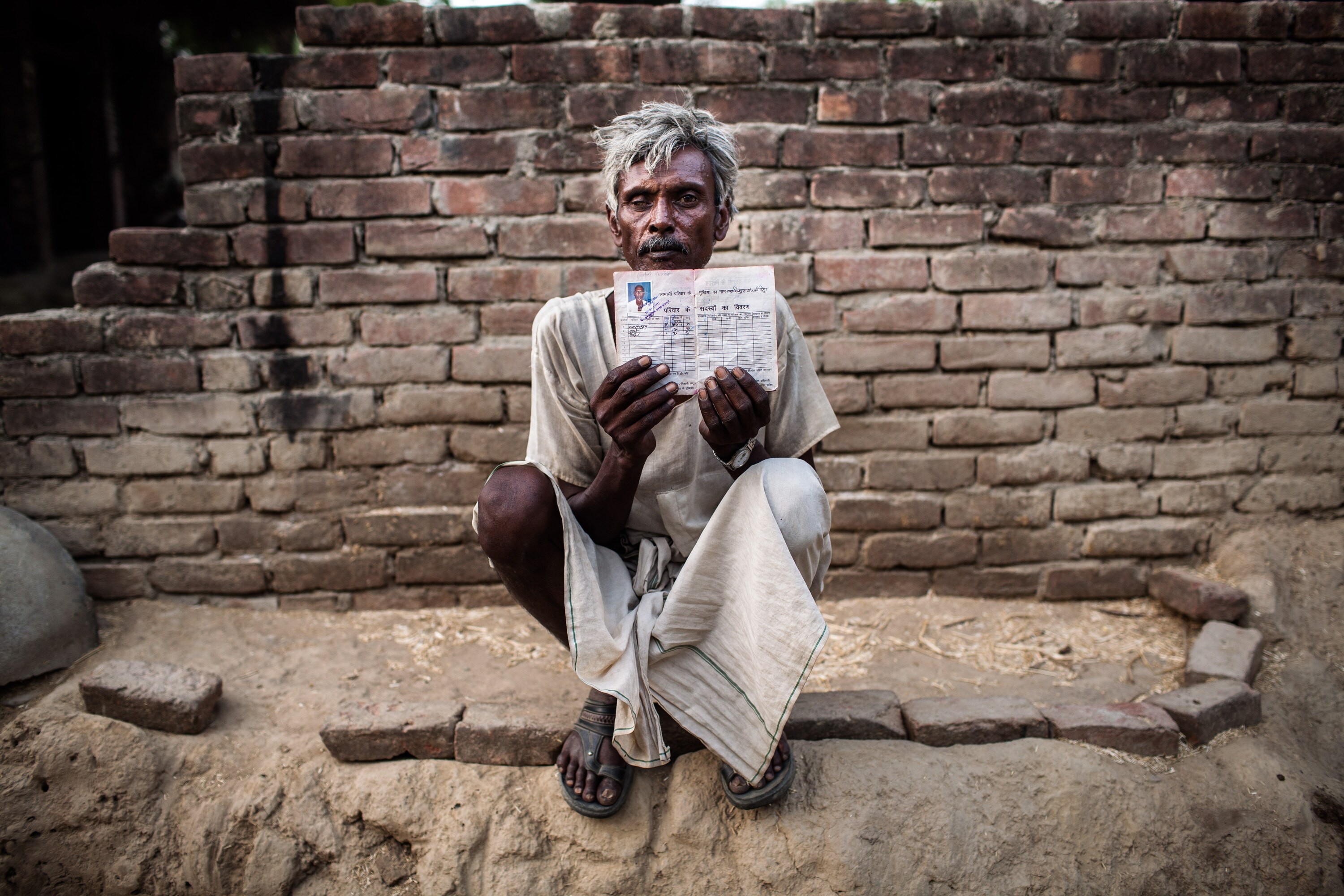

Payment Delayed For Work Done

There is another argument for a higher NREGA budget: the government must do something urgently to break the vicious cycle of wage arrears. During the last few years, each financial year opened with a large balance of NREGA wage arrears – nearly Rs 10,000 crore in 2019-20. After the arrears are paid, too little is left to meet the demand for NREGA work, leading to a new wave of wage arrears around the end of the financial year, carried over to the next year. To break this vicious cycle, and ensure that NREGA workers are paid within 15 days as prescribed under the law, the budget needs to be increased.

This vicious cycle, however, is only one aspect of the chronic problem of delayed and unreliable NREGA wage payments. The government claims that timely payment has become the norm, but its own data tell a different story. According to the official NREGA website, more than one-third of the wage transaction requests sent last October are still pending. In Karnataka and Rajasthan, no wage payments have been made in the last four months. Further, it is well understood that some delays remain unrecorded. To be fair, the Ministry of Rural Development is working on this, and some aspects of the payment process have improved, but assured payment within 15 days is still an elusive goal.

In recent years, delays have been compounded by a new generation of payment problems including rejected payments, diverted payments, and blocked payments.

- Rejected payment means that a money transfer bounces, possibly due to faulty account details or data entry errors.

- Diverted payment refers to money being sent to a wrong account.

- Blocked payment refers to the situation where a worker's account has been credited but it is blocked, e.g. for lack of ‘e-KYC', the biometric verification of her Aadhaar number.

According to the NREGA website, a staggering, Rs 1,600 crore of wage payments were rejected so far in 2019-20. Rejected payments are accompanied by a bewildering collection of error codes that are often difficult to understand, even for professional bankers. To illustrate, it took a full two years for the combined expertise of the Ministry of Rural Development, the Unique Identification Authority of India and the National Payments Corporation of India to clarify the meaning of “inactive Aadhaar” as an error code, in response to queries sent under the Right to Information Act. As this example illustrates, the Aadhaar Payment Bridge System—imposed without consent on NREGA workers— is responsible for many of these technical glitches.

Delayed and unreliable wage payments have been the bane of NREGA for years.

This has sapped workers' interest in a programme that depends in multiple ways on their active involvement – in the work application process, the planning of works, the conduct of social audits, the formation of workers' unions, and more. When workers lose interest, corrupt middlemen have a field day. Thus, timely and reliable payment is important not only to safeguard workers' rights but also to prevent corruption. On both counts, recent experience is very sobering.

No Longer Fair Wage

This brings us to a final argument for a higher NREGA budget: wage rates are begging to be raised. For almost ten years now, NREGA wages have been held constant in real terms – money wages have been raised each year in tandem with the price level, but not more.

NREGA wages (currently around Rs 200 per day on average) have fallen behind market wages, all the more so when payment delays and uncertainties are taken into account. In many states, NREGA wages have also fallen behind statutory minimum wages, turning NREGA into a breaker – instead of enabler – of minimum-wage laws. Low wages have further alienated NREGA workers, already discouraged by haphazard payments. They are not demanding a dole but a basic wage for honest, productive work.

When Technology Becomes An Obstacle

NREGA is a demand-driven employment programme. Workers have a right to employment on demand, minimum wages, and payment within 15 days. Making the requisite financial provisions is a legal obligation. Along with this, of course, steps must be taken to ensure that the money is well used. Indeed, fake muster-roll entries (bogus work attendance) have not disappeared – far from it. The government is under the sweet illusion that digital technology and Aadhaar have reduced NREGA leakages, but this is extremely doubtful, if not the opposite of the truth.

Digitisation has reduced some vulnerabilities but created new ones, such as fraud by – or in collusion with – data-entry operators.

Contrary to official belief, digitisation has also failed to ensure transparency, at least for now. The main reason is that NREGA's ‘management information system' is a maze, virtually impossible to navigate for NREGA workers even if they have access to the internet. Those who have the strongest stake in preventing leakages are cut off from this vital information.

In short, the revival of NREGA calls for clearing wage arrears, raising wage rates, ensuring timely payment and a new generation of anti-corruption measures. All this, in turn, requires a restoration of political support for the programme, much diminished in recent years.

None of this is likely to be music to the ears of business leaders and corporate analysts. But the idea that workers should be exploited to the maximum is both medieval and short-sighted. India's battered, undernourished, insecure and ill-educated workforce is hardly an asset for the economy or the nation. Giving rural workers their due is not just elementary fairness but also good economics.

Jean Drèze is Visiting Professor at the Department of Economics, Ranchi University.

The views expressed here are those of the author, and do not necessarily represent the views of BloombergQuint or its editorial team.

Essential Business Intelligence, Continuous LIVE TV, Sharp Market Insights, Practical Personal Finance Advice and Latest Stories — On NDTV Profit.