As Finance Minister Arun Jaitley prepares to present his final budgetary document via a vote on account next month, he can justifiably claim some success in improving the country's finances. The fiscal deficit is lower by a percentage point of GDP now compared to when Jaitley took over, helped in part by a period of low oil prices. But Jaitley's fiscal record is not unblemished. The revenue deficit has remained above targets, below-the-line bond financing has made a come-back and public sector borrowings have added to the overall public debt burden.

Meeting Fiscal Targets

In the year before Jaitley took over, the central government's fiscal deficit was just short of 5 percent. The Congress party-led United Progressive Alliance government had chosen to support the economy with fiscal stimulus after the global financial crisis but failed to withdraw the stimulus in time. By 2009-10, the fiscal deficit had hit 6.5 percent of the GDP. The process to bring the deficit back under control began the year after and Jaitley remained committed to it.

A period of low oil prices certainly helped but the government also took some fiscally prudent steps along the way, such as deregulating diesel prices in October 2014.

Till 2016-17, the government was sailing along on its attempts to bring down the fiscal deficit closer to the elusive 3 percent mark. However, the implementation of the Goods and Services Tax and a higher-than-expected burden to recapitalise banks has thrown the plan off the track. The government missed its fiscal deficit target of 3.2 percent of GDP in 2017-18, with the deficit settling at 3.5 percent eventually.

Between April-November 2018, the fiscal deficit had hit 115 percent of the target, leaving economists to question whether this year's goal of 3.3 percent would be met.

De-Emphasising The Revenue Deficit

It could be argued that at near about 3.5 percent, the central government's fiscal deficit is reasonable even if it hasn't hit the medium-term target of 3 percent. But Jaitley's track record in bringing down the revenue deficit has been less favorable. As per the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management Act (2003), the revenue deficit was to be eliminated by 2008-09. The revised FRBM Act pushed back that target to March 2015.

The successive governments, however, found it difficult to move closer to this target. While Jaitley has managed to bring this down to 1.9 percent from 3.1 percent in 2013-14, in the last budget his government decided to abandon targetting of the revenue deficit. This drew criticism from the fiscal purists but the government argued that the difference between revenue deficit and fiscal deficit is cosmetic. “In a country like India, there is little or no evidence to say that capital expenditure should enjoy pre-eminence,” the government had said, adding that the maintenance expenditure in a country like India, which may be counted as revenue expenditure, is as important as capital expenditure.

For the current year, the government expects the revenue deficit to be at 2.2 percent of the GDP, although this is not a formal target. Between April-November 2018, the revenue deficit was at 132 percent of the projection.

Beyond The Balance Sheet

Not unlike previous governments, Jaitley too has resorted to off-balance sheet financing of items that prove to be too large to absorb within the stated fiscal deficit. If the UPA government chose to do this to deal with subsidies by issuing oil and fertiliser bonds, the Prime Minister Narendra Modi-led government has gone down the same route to recapitalise banks. Of the Rs 2.11 lakh crore in funds allocated for recapitalising public sector banks, Rs 1.35 lakh crore is coming via bonds.

“Furthermore, other off-balance sheet borrowing (e.g. Food Corporation of India) and borrowing by public sector enterprises together has also increased consistently over the last five years from an average of about 1.1 percent of GDP to 1.8 percent of GDP in 2017-18,” said Sajjid Chinoy, chief India economist at JPMorgan in a report last week.

Just ahead of the completion of the current government's tenure, it also got a rap on the knuckles from the Comptroller and Auditor General. In a review of the compliance track record with the FRBM Act, the national auditor flagged off a rise in off-balance sheet liabilities, particularly via carry-over of subsidy spends. While this is not a new phenomenon, the proportion of subsidies being rolled over has risen. If off-budget items are accounted for, the government's liabilities would be higher than reported, said the CAG.

The government's outstanding liabilities will gain significance in the coming years as the NK Singh committee set up to review the fiscal framework has recommended that the central government's debt to GDP ratio be brought down to 40 percent by 2023.

Shifting Composition Of Borrowings

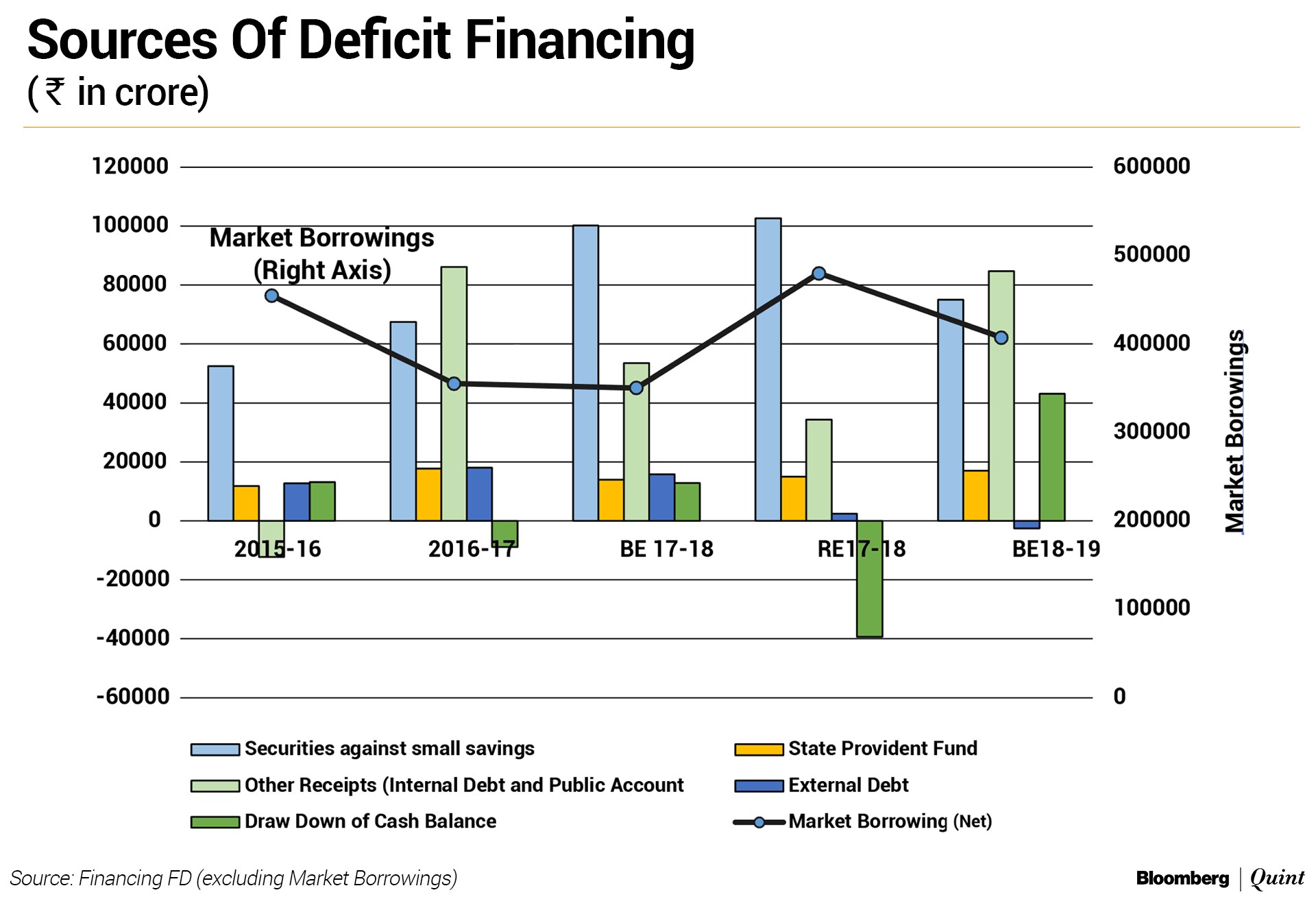

The mix of borrowings used to finance the deficit has shifted over the tenure of the current government.

Following the recommendations of the Fourteenth Finance Commission, the central government got more room to borrow from the National Small Savings Fund. The government, particularly over the last two years, have used this provision actively.

Not only has the government used the NSSF for financing its deficit, public sector companies like the Food Corporation of India Ltd., the National Highway Authority of India and Air India have also borrowed from this pool of funds.

In FY18, the government borrowed Rs 1 lakh crore from the NSSF. In the current fiscal, it had budgeted for Rs 75,000 crore in borrowings from the fund.

While on the one hand, this allows for market borrowings to be kept in check, it can distort bank deposit rates if the government keeps small savings rates artificially high.

Essential Business Intelligence, Continuous LIVE TV, Sharp Market Insights, Practical Personal Finance Advice and Latest Stories — On NDTV Profit.