(Bloomberg) -- Pakistan went to the polls last week in an election that many thought would be a formality.

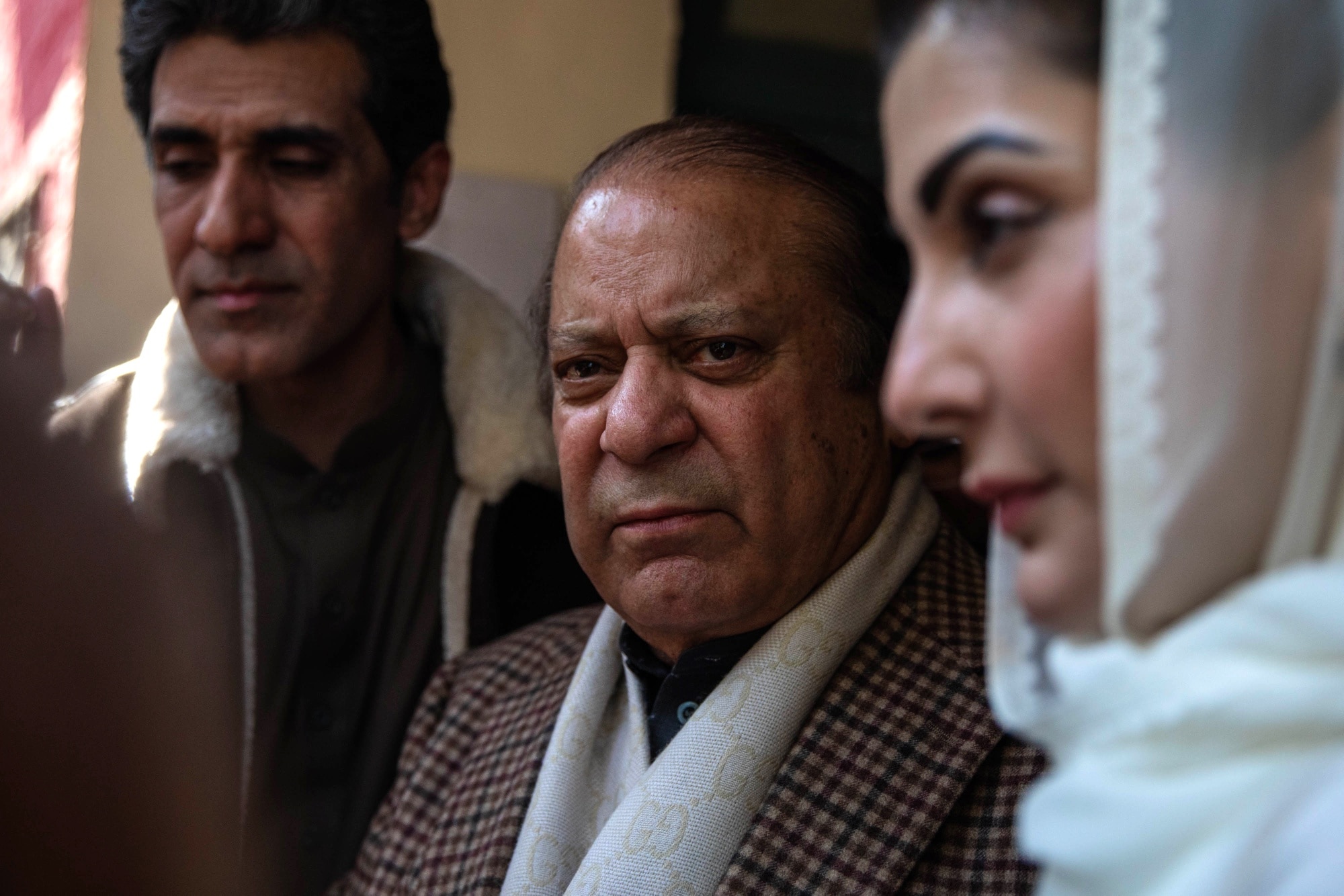

Former cricket star Imran Khan was in jail, his party banned from running under its own banner or even using its famous cricket bat symbol. Analysts said the powerful military gave its blessing for the three-time former premier Nawaz Sharif — or anyone else other than Khan — to take power, and Sharif's return was the most likely outcome.

But in a surprise development, Khan loyalists — running as independents — thrived, winning the most seats of any group. Their against-the-odds performance highlighted voters' disillusionment with the status quo of Pakistan's politics, which is dominated by two family-controlled parties and, analysts say, the powerful military. It was also a triumph for democracy, leaders from Khan's party said, as the people of Pakistan demanded to be heard.

But even though candidates from Khan's Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf party, or PTI, won the most seats, they may not form a government. That's because they don't have a simple majority, and the two other main parties may join forces. Khan supporters, who argue authorities are attempting to influence the outcome, took to the streets Sunday but not in large numbers, deterred by a heavy police presence.

Here's what you need to know about the historic election.

Which party won?

Independents, the vast majority of whom are Imran Khan loyalists, took 101 of the 265 contested lower-house seats. Sharif's Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz won 75, while Bilawal Bhutto Zardari's Pakistan Peoples Party got 54.

All parties fell short of a simple majority of 133 seats. That is not surprising. Since military rule ended in 2006, no single party has won an outright majority.

What happened next?

The Sharif and Bhutto parties held talks on joining forces, a move that analysts say is likely backed by the military, but they haven't yet reached an agreement yet.

Meanwhile, Khan's PTI has been complaining about the results, which it claims are being manipulated. It wants more transparency on the count. The US, European Union and UK have expressed similar concerns, while Pakistan's foreign ministry disagrees.

What's likely to come now?

The most likely scenario is Sharif's party will broker a deal with Bhutto Zardari's PPP. Both parties could then attract other parties to the coalition and even some of the Khan-backed candidates. Sharif, or his brother, Shehbaz, would probably then become prime minister again.

Let's not forget that despite the Sharif and Bhutto clans' public opposition to each other, they formed a government together after Khan's ouster in April 2022.

It's unlikely, but not out of the question, that Bhutto Zardari, the son of assassinated former premier Benazir Bhutto, could end up negotiating to lead any coalition. He has some leverage, and at 35, he argues that he represents a fresh face in a country where more than 60% of the population is under 30.

It's harder to see a scenario where Khan's PTI forms a government given the military's opposition to it, analysts say. But one pathway would be to form an alliance with another party.

How will Khan's supporters respond?

One question is how much Khan's supporters will push back. Remember, the military already clamped down on PTI last May when supporters attacked government and military buildings after Khan was detained. Some observers say they're unlikely to have the appetite for another confrontation.

What does this mean for the military?

It's not the outcome the military would have wanted. The support for Khan's loyalists is a demand for true democracy and a protest against the status quo. It's also clearly a protest against the military itself.

One question is what the army will do next. Pakistan's generals have stepped in three times in the country's history to directly rule the nuclear-armed nation. The last time was in 1999 when General Pervez Musharraf ousted Sharif's government in a bloodless coup. Analysts say it's unlikely to do the same this time, and will continue to make decisions behind the scenes.

What does it mean for markets?

Investors are focusing on whether Pakistan can negotiate a new bailout from the International Monetary Fund for when the current program expires next month. Any delay in reaching an outcome from the election is likely to impact that, which is why Pakistan's stocks fell the most in two months on Friday, while bonds also dropped.

“The market needs clarity,” said Bilal Khan, head of international sales at Karachi-based brokerage Arif Habib Ltd. “The election was on Feb. 8 and we still don't know who is forming the government.”

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.

Essential Business Intelligence, Continuous LIVE TV, Sharp Market Insights, Practical Personal Finance Advice and Latest Stories — On NDTV Profit.