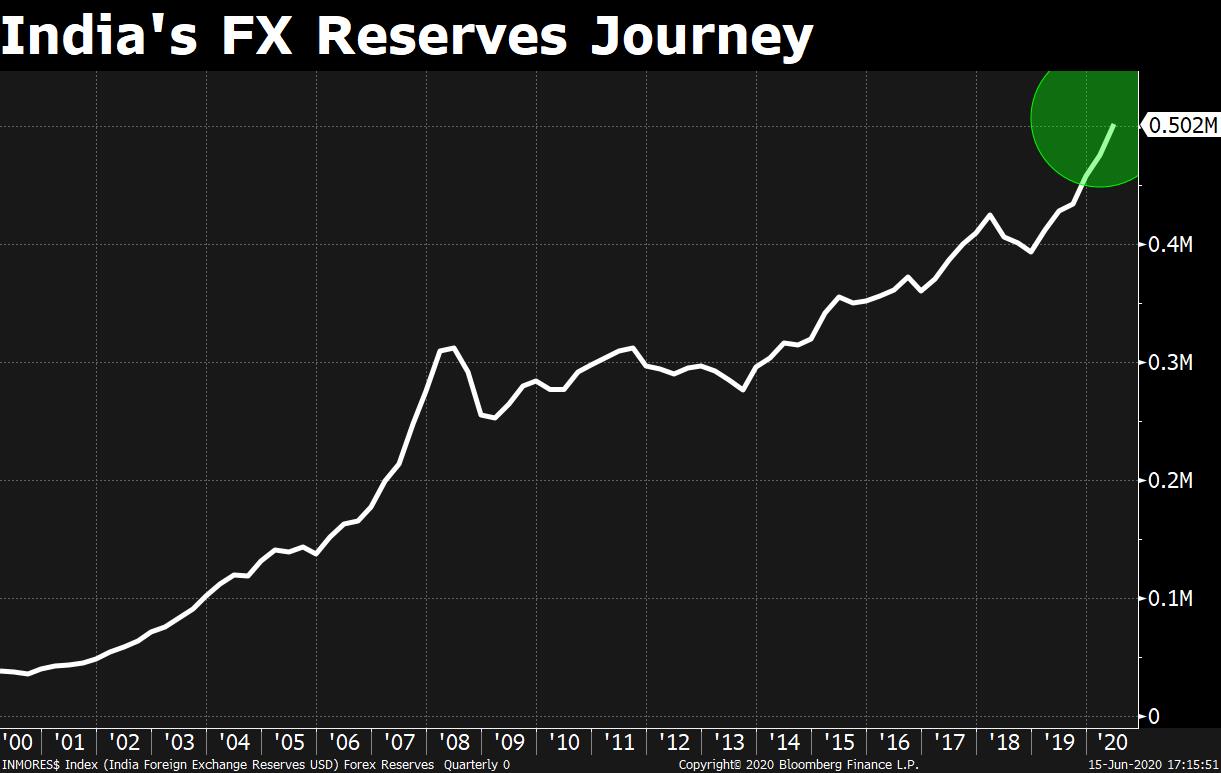

India now has half a trillion dollars of foreign exchange reserves. Those reserves cover 12 months of the pre-Covid-19 level of imports. They are about 88% of India's external debt which stood at $564 billion as of December 2019.

Every economic indicator has its day in the sun and forex reserves are not immediately in focus as India does not face an external sector crisis. Yet, the reserves form a crucial cushion at a time of extreme global uncertainty.

India hasn't always had that comfort. From the crisis of 1991 and beyond, there have been a number of episodes where India has felt insecure about the level of reserves.

From BoP Crisis To Asian Financial Crisis

The 1991 crisis is an obvious place to start when chronicling India's foreign exchange.

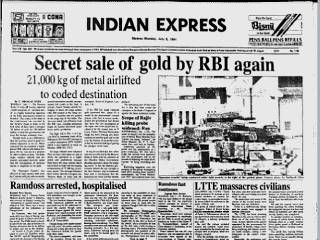

The story of that year is, of course, well-told. India's forex reserves stood at $5.8 billion as of March 1991 and dwindled further during the course of that year, prompting the country to ship out its gold to avoid a default. The crisis eventually led to the liberalisation of the Indian economy.

A by-product of those reforms was an increase in reserves, which, according to the RBI's annual reports, was driven in large part by foreign direct investment in the early years.

That year brought the Asian Financial Crisis and the first test of India's external sector since liberalisation.

Beginning September of that year, volatility in the foreign exchange markets forced large spot forex operations from the Reserve Bank. This was done “to restore orderly conditions and quell adverse market expectations,” the central bank's annual report for that year shows.

While the RBI sold forex when needed, periods of calm also allowed it to continue building reserves. For the year 1997-98, the central bank managed net purchases of $3.8 billion, which added to foreign currency assets. That was the year in which the RBI also wound down the FCNR-A scheme and saw $2.4 billion in outflows under that. The scheme, under which the forex risk was borne by first the RBI and then the government, had been stopped in 1993.

Net of outstanding forward liabilities, the Reserve Bank's foreign exchange reserves stood at about $27.6 billion at the end of that financial year.

The following year brought more challenges. This time local.

May 1998 saw the Pokharan nuclear tests and economic sanctions on India followed. This led to the launch of the ‘Resurgent India bonds', which resulted in an accretion of foreign currency assets of $3.5 billion, the central bank's annual report for that year shows.

Beginning The 2000s On A Steady Note

The new century began on a reasonable note for India's forex reserves.

As of March 2000, India's forex reserves stood at about $37 billion. Reserves were steady but still modest by some metrics. In a speech in 2000, Bimal Jalan, then governor of the RBI, detailed the emerging thinking on forex reserves, making it clear the central bank would continue to build a buffer.

Jalan said that while the earlier rule of thumb for adequacy of reserves was in terms of months of imports, it was increasingly felt that reserves should also be adequate to cover likely variations in capital flows. He cited the ‘Guidotti-Greenspan rule' which argued that reserves should be adequate to cover one year's import and capital flow requirements. “In India, we are taking into account liquidity as well as import requirements and unforeseen contingencies in the management of reserves,” Jalan said.

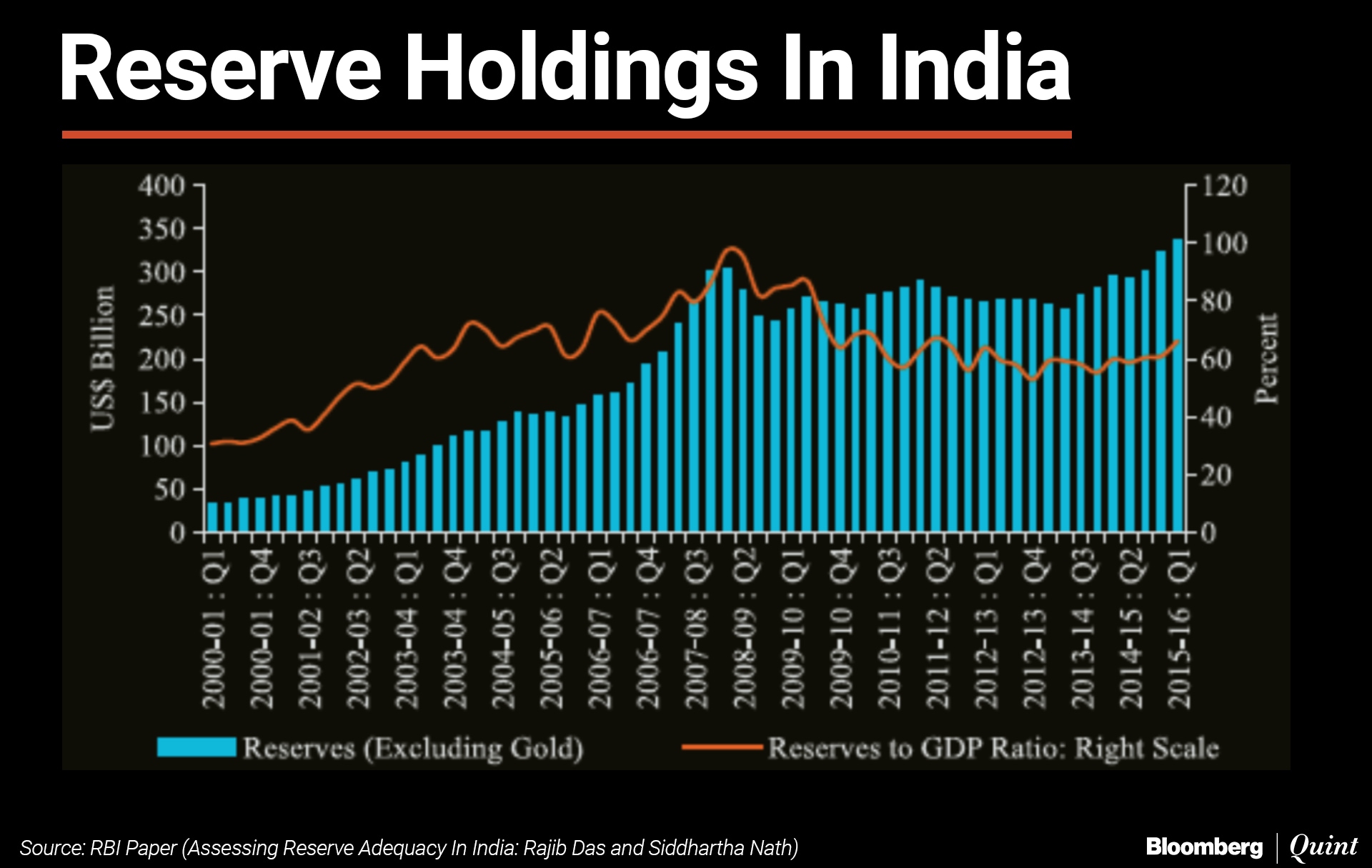

In a paper dated November 2016, Rajib Das and Siddharth Nath of the RBI's Department of Economic Policy Research, explained that a low current account deficit helped with accumulation of reserves through the period of 2001-07.

During these years, India's CAD averaged 0.1% of GDP, while capital flows were strong. India's reserves increased by $232 billion between Q1 2001-02 and Q1 2008-09, a period in which cumulative net FPI inflows stood at $66.3 billion, the paper noted.

As a percentage of GDP, reserves peaked at about 94% in 2008-09, data included in the paper showed.

From Global Financial Crisis To Taper Tantrum

Vulnerabilities in the Indian economy started to rise once again in the aftermath of the global financial crisis, which eventually brought the external sector under stress and forex reserves into spotlight again.

The inability to pull back on post global financial crisis fiscal stimulus in time led to wider twin deficits and high inflation. During this period, as the data from the Das and Nath research above showed, forex reserves as a % of GDP also slid.

And so when volatility hit the global markets, foreign investors saw India as vulnerable once again. As the currency tumbled and the designed monetary policy response failed to act as protection, the RBI sold dollars heavily.

Once again, India found itself in a position where the adequacy of its reserves came into question. As of August of 2013, forex reserves of about $275 billion were adequate to cover less than seven months of imports.

On September 4 that year, the central bank announced a special swap scheme to draw in foreign currency non resident deposits. The central bank offered a special swap window at a fixed rate of 3.5% per annum for FCNR (B) funds mobilised for a minimum tenor of three years or more. Banks raised $26 billion under the scheme.

And yet another external sector crisis passed.

Adequacy Of Reserves: Debate Continues

At $500 billion, adequacy of reserves does not appear to be a concern for the Indian economy at this stage. Yet, a rethink on the issue of judging reserve adequacy is underway at the central bank. The rethink may be needed not just on how much in reserves is adequate but also how much is too much. After all, forex reserves are invested in low-yielding assets such as U.S. treasuries and do subject the central bank balance sheet to volatility.

As part of a wider review of the RBI's economic capital framework in 2019, a committee headed by former governor Jalan made a few important observations with regards to forex reserves.

First, while forex reserves provide the economy with a buffer against external stress, they give rise to significant risks for the RBI balance sheet, the report pointed out. The committee pointed to the fact that mark-to-market losses of 1.1-1.5% of GDP have been experienced during certain periods, although the RBI has never suffered an overall loss in any year.

In making that point, the Jalan committee was urging that the overall economic capital framework and reserve position of the central bank be viewed in the context of the risks that lie on its balance sheet.

The committee also noted that foreign exchange reserves (then at about $400 billion) were significantly lower than the country's total external liabilities ($1 trillion) and even lower than total external debt ($500 billion).

Also Read: Even With $500 Billion Warchest, RBI Won't Let Rupee Climb

“This needs to be taken into account in assessing the external risk being faced by the country and the possibility that the RBI may be required to increase the size of its forex reserves with its concomitant implications for the balance sheet, risks and desired economic capital,” the report said.

It, however, did not delve further into the adequacy of reserves, leaving that to an internal committee, whose report is awaited.

Ira Dugal is Editor - Banking, Finance & Economy at BloombergQuint. The author would like to thank comments on social media by Alpana Killawala and Kalyan Ram, which prompted this column.

Essential Business Intelligence, Continuous LIVE TV, Sharp Market Insights, Practical Personal Finance Advice and Latest Stories — On NDTV Profit.