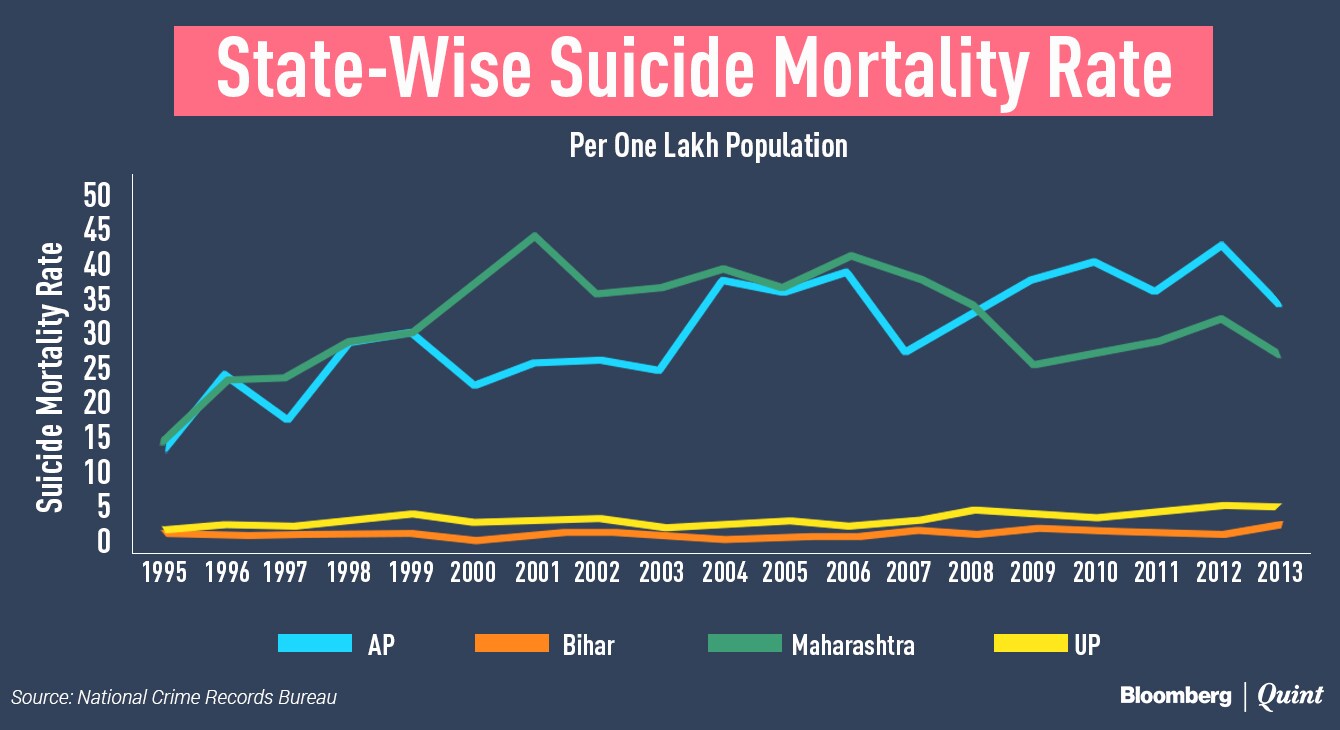

Over time, the organised demands for farm loan waivers have gotten strong, sustained and shrill, leading to several state governments giving in to the farmers' demands. Looking at the data on farmer distress, however, several puzzles remain. Why is it that the suicide mortality rates of farmers in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar are consistently lower than Maharashtra and Andhra Pradesh?

Is there less distress in the poorer states than in the relatively more affluent ones?

If farmer distress is driven by indebtedness, then we must understand the exact nature and magnitude of this indebtedness. The level of indebtedness in a population can be measured as Incidence of Indebtedness which is the percentage of households in a population that are in debt from formal or informal creditors. The data reveals that there is a great deal of convergence across states in Incidence of Indebtedness. The national average is 31 percent (2013) and states like Maharashtra (31 percent), Bihar (29 percent) and UP (30 percent) are similar in the magnitude of overall debt.

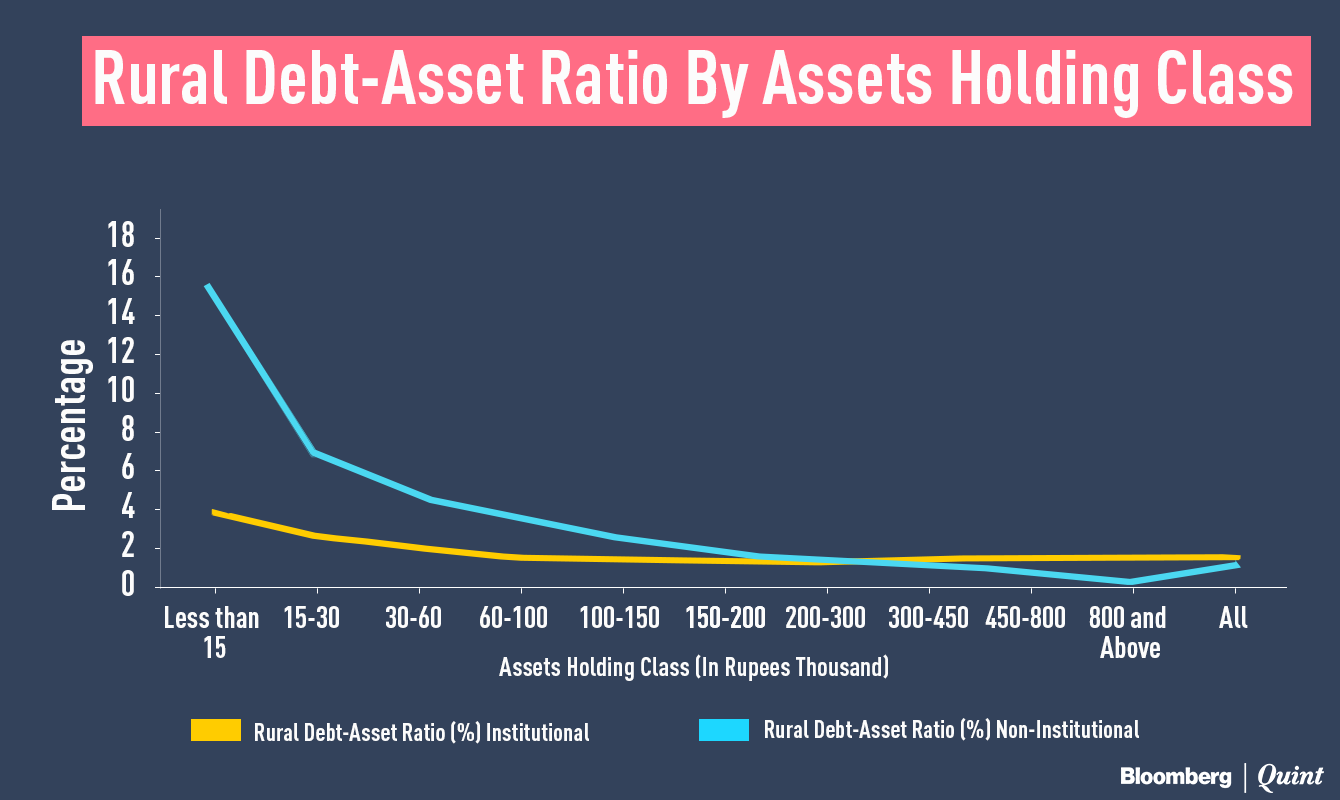

Farmers take loans from formal institutional sources as well as informal moneylenders. Data reveals that the debt-to-asset ratio looks very different for the poor and rich farmers. National Sample Survey Office (NSSO) data shows that poorer households have a much higher debt-to-asset ratio and hold more of both institutional as well as informal loans. This leads to our second puzzle: 86 percent of all farmer suicides in Maharashtra are by farmers owning more than 2 acres of land and 60 percent by farmers owning more than 4 acres.

There is little correlation between poverty and suicides among farmers. What are we missing?

Also Read: Punjab To Waive Crop Loans Of 8.75 Lakh Small And Marginal Farmers

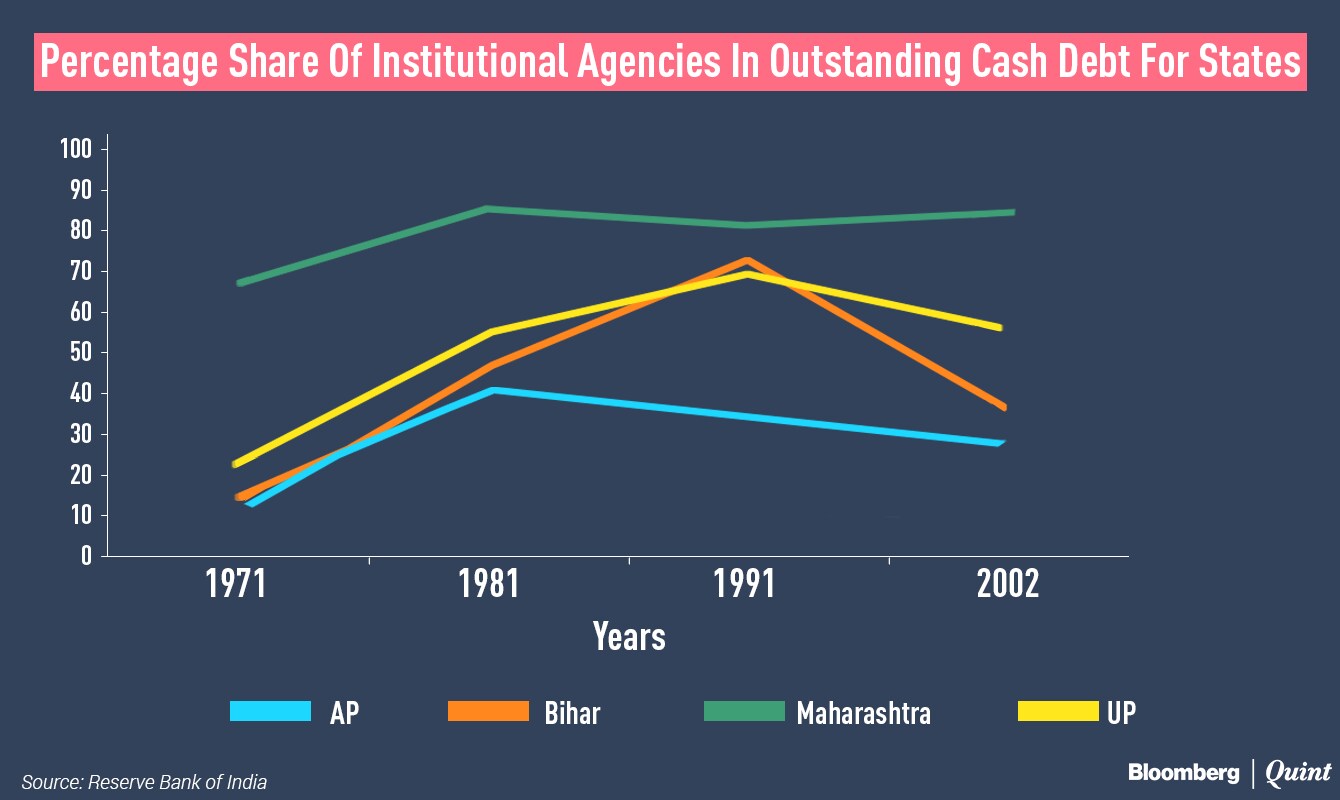

It is generally believed that informal loans from moneylenders are extremely expensive and exploitative. The overriding objective behind most subsidised credit schemes of the government since the 1950s has been to replace the blood-sucking moneylenders (à la 1957 Bollywood movie Mother India). If we study the data, we observe that formal loans account for 87 percent of total outstanding debt in rural Maharashtra. That penetration of formal credit is way above the national average of 57 percent, and the levels in Bihar and U.P. are far more modest.

This leads to the third puzzle: despite very high banking coverage in rural Maharashtra and lower dependence on exploitative moneylenders, there are significantly more farmer suicides there than in all other poorer states of the country.

What is happening?

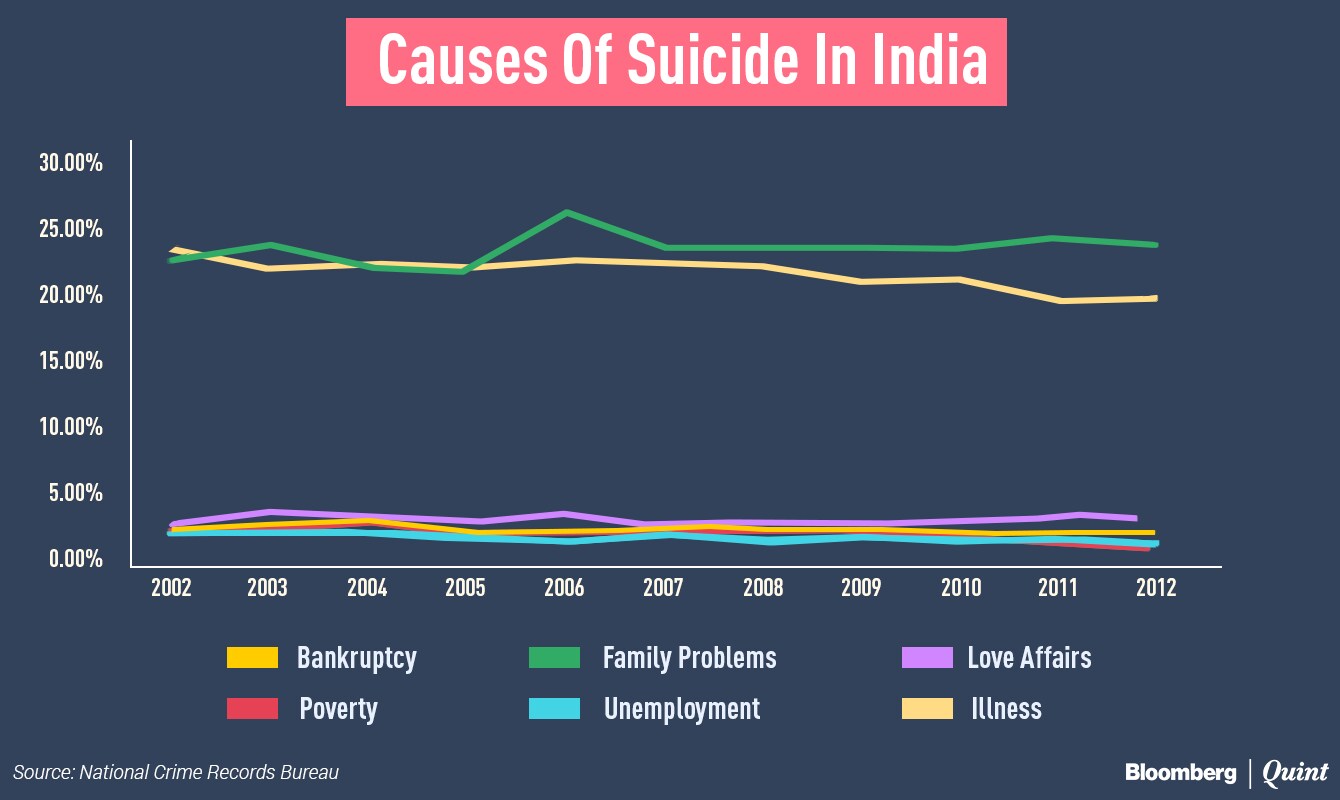

Until 2013, there was no mention of ‘debt' in the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) data for ‘causes of suicides'. This was usually proxied by the ‘Bankruptcy or Sudden change in Economic Status' variable. Now if you look at the overall data, the most commonly cited cause of suicide was ‘family problems' or ‘illness'. This was also true for Maharashtra where farmer suicides comprised 35 percent of all suicides but ‘Bankruptcy or sudden change in Economic Status' accounted for only 5 percent of these.

Also Read: Farm Loan Waivers: The Economics And Politics Of Indian Agriculture

Since 2014, the NCRB has started reporting data separately for farmers. This is a welcome move, given the political sensitivity around the issue. NCRB has also started reporting ‘indebtedness' as a cause for suicides. While it is extremely difficult to now study time trends given that the aggregate data is being reported under new categories, there is a bigger puzzle that emerges from this: in last two years, the number of farmer suicides due to ‘indebtedness' has increased by 88 percent!

Beyond the quibbles of data and metrics, we must agree that farmer distress is not limited to bank loans alone.

There are several other causes and we must go back to first principles in thinking about policy recommendations. Illness is a leading cause that has seldom received the policy priority it deserves. Access to healthcare, access to broader rural infrastructure and connectivity as well as the policies and politics of minimum support prices – there remain several other elephants in the room that need handling. Loan waivers are not the panacea that they are politically made out to be.

Shamika Ravi is a Senior Fellow of Governance Studies Program, at Brookings India and Brookings Institution Washington D.C.

The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of BloombergQuint or its editorial team.

Essential Business Intelligence, Continuous LIVE TV, Sharp Market Insights, Practical Personal Finance Advice and Latest Stories — On NDTV Profit.