The direction of causality between income growth and credit growth has been debated for decades. While there is a strong argument for the case that growth in the gross domestic product facilitates development of the financial system and credit markets, it is also posited that evolved credit facilities enable greater economic growth through the channels of investment and private consumption.

Irrespective of the causality, when credit growth substantially outpaces the GDP growth, overstretched credit markets and excessive leverage leave the economy susceptible to financial crises. Is there a cause for concern for the fastest growing emerging economy, India?

The GDP-Credit Nexus In India

According to the IMF, India's real GDP growth is projected to be 6.8% in 2024 and 6.5% in 2025, against a global growth rate of only 3.2%. Over the last two years, the real GDP grew 7% and 7.7%, while bank credit grew 13.1% and 14.6%. Among other emerging market and developing economies, China and Russia witnessed credit growth at around 10%, while Brazil faced a slowdown owing to high inflation and interest rates. This raises the question about whether India's robust GDP growth warrants an even higher credit growth rate.

India's domestic credit to the private sector as a share of the GDP is only 50.4%, against a global average of 143.9%. While this ratio steadily increased post-liberalisation from 20% levels, it has stagnated around 50% since 2010. This is often seen as a setback to India's growth potential, where higher leverage in the economy could sustain consistently higher growth rates. However, the 2008 financial crisis was the epitome of how excessive exposure, coupled with lax regulation, can dismantle a financial system, and eventually depress the entire economy. Given the momentum of Indian growth in recent years, it might be tempting to throw caution to the wind and aggressively expand credit in the system, but the official stance has been prudent with increased priority to regulation.

Of course, one should not discredit the argument that credit expansion can drive economic growth in India. Greater supply of credit fosters private investment and allows consumers to smoothen their consumption curve at a higher level. Given the consumption driven nature of Indian growth, arguing against the expansion of credit would be ignorant and detrimental; instead, India should focus on the rate of expansion and the quality of credit. A line needs to be drawn between the proliferation of unsecured, risky credit and the balanced expansion of collateralised, productive credit — which is exactly what the RBI has been doing through tightening of lending norms and increased risk-weight allocations. But how much can a little optimism hurt the economy?

Revisiting Minsky

The unbridled expansion of credit in the absence of regulations, resulting in mass defaults and the eventual collapse of the financial system can be better understood through Hyman Minsky's 'financial instability' hypothesis. The American economist claimed that the economy moves through three phases in an economic cycle — hedge, speculative and ponzi. The initial precautionary hedge phase experiences modest leverage, low risk and balanced credit in the system, since both borrowers and lenders are wary in the aftermath of the previous cycle's bust. As conditions ease and growth picks up, there is optimism in the economy, driving up asset prices backed by higher income levels and easier credit facilities. In this speculative phase, easy availability of credit and confidence about a sustained boom increases leverage manifold; exuberance also leads to innovation of risky financial instruments before regulators can intervene.

In the final stage, when the economy is over-leveraged and the GDP growth is unable to keep up with credit growth, an economy-wide credit default sets in, dubbed as the 'Minsky moment'. This ponzi stage is associated with mass panic, where a domino effect leads to the sequential collapse of most credit instruments, finally impacting the asset markets with crashing prices. While sometimes the Minsky moment is exacerbated by policy interventions, the US financial crisis has exhibited how potent credit markets can be for kicking off an economic bust.

Credit Where Credit Is Due

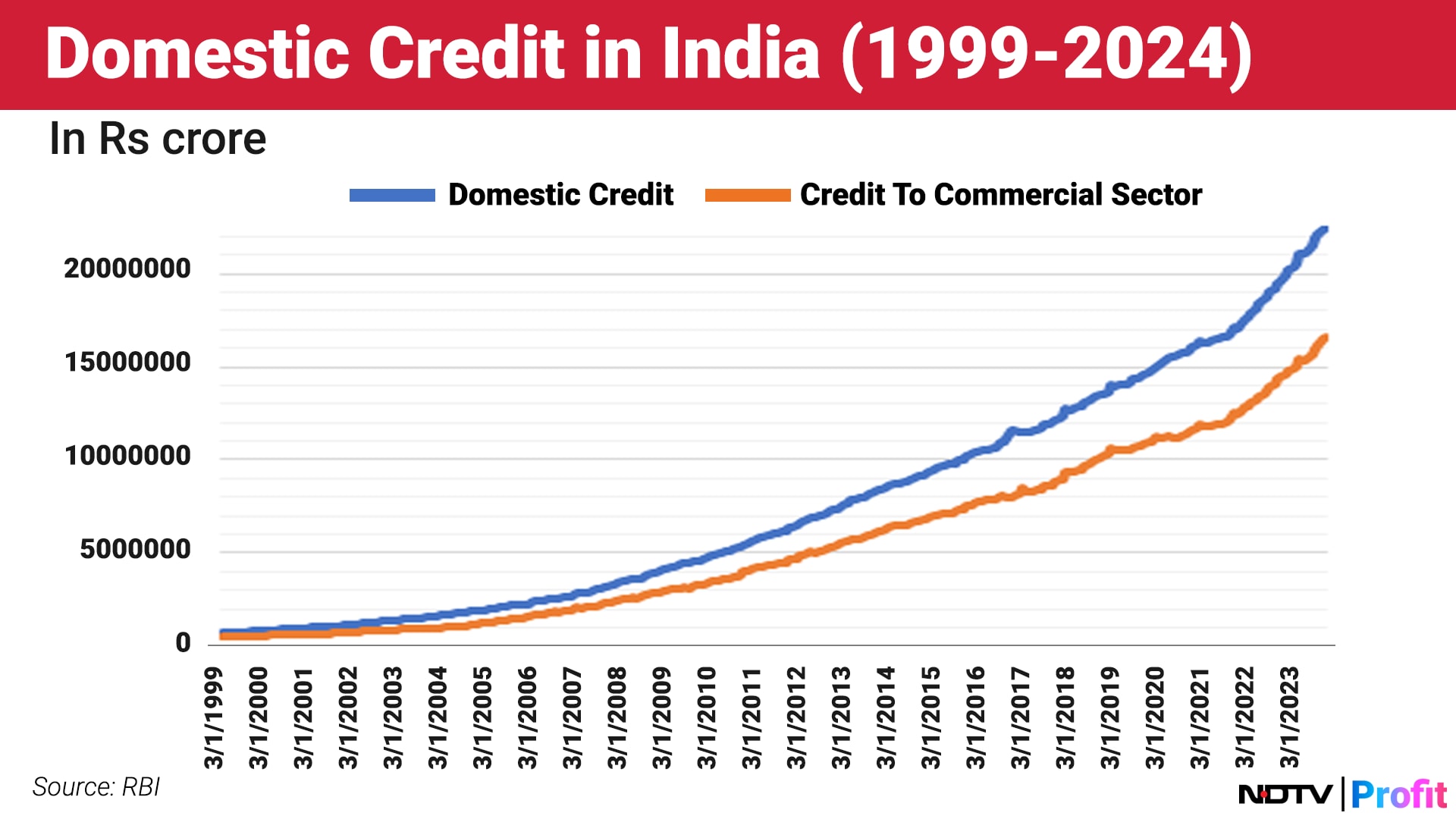

Domestic credit has exhibited a secular rise over the last two decades, with the share of credit to the government continuously increasing (the gap between total and consumer credit). In addition, the deployment of bank credit towards personal loans has increased 18% in the last year.

A growing Indian middle class with optimism about the economic prospects of the country (as captured in the RBI Consumer Confidence Survey), can explain how credit is financing consumption to meet the aspirational needs of the modern Indian. If sustained, this could have provided the impetus needed for the Indian Minsky moment, but the RBI's macroprudential surveillance and continuous assessment of financial stability came in the way.

Identifying the potential risks, in a notification dated Nov. 16, 2023, the RBI enforced measures to tackle the rampant expansion of consumer credit. The risk weight on personal loans has been increased from 1005 to 125%, while that on credit card receivables has been revised to 150%. In addition, all lenders have been advised to implement sectoral exposure limits, especially for unsecured consumer credit. While the risk weight on personal loans is not levied on vehicle loans, they will be treated as unsecured credit and be subject to corresponding prudential limits.

The risk weights on housing loans were rationalised in 2020 but they have been reset to pre-pandemic limits now — varying between 30% and 50%. Although housing loans are asset-backed, raising the risk-weights should be considered, especially when housing loans have grown at around 35% in this fiscal. The 2007–08 crisis should serve as a reminder of how a euphoric asset boom can quickly spell doom for the entire economy. As increasingly-affluent Indians reap the benefits of economic growth, invigorating the demand for physical assets, the RBI should be cautious and restructure the prudential limits on housing loans to negate all possibility of an Indian Minsky moment.

Arya Roy Bardhan is a research assistant at the Centre for New Economic Diplomacy, Observer Research Foundation.

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of NDTV Profit or its editorial team.

Essential Business Intelligence, Continuous LIVE TV, Sharp Market Insights, Practical Personal Finance Advice and Latest Stories — On NDTV Profit.