As India gets ready to vote in the crucial Lok Sabha elections this month, one issue has taken centre-stage in the political narrative: jobs.

Ever since a leaked report of the National Sample Survey Office showed unemployment at a 45-year high last fiscal, the opposition has criticised Prime Minister Narendra Modi's administration for its failure to provide enough jobs. The issue of jobs also became a focus area in Congress' manifesto which was released on Tuesday.

Yet, with so much political debate around employment, no one has been able to provide empirical evidence or a solid strategy on how more jobs can be created.

One economic researcher seems to believe the answer lies in easing of the country's fiscal deficit targets. In a recent paper for the Azim Premji University, Srinivas Thiruvadanthai, director of research at Jerome Levy Forecasting Center, argues that India needs to look past the stigma of high fiscal deficits and use budgetary resources to promote robust job creation.

“The central government has enough fiscal space to adopt a robust employment generation policy,” Thiruvadanthai wrote. “Fiscal expansion aimed at job creation would also serve to accelerate growth, help the corporate sector repair its balance sheet, and alleviate the non-performing loans in the banking sector.”

No matter how many employment generation programmes are created and how well they are designed, if inadequately funded, these programmes will fail to create a meaningful increase in employment.Srinivas Thiruvadanthai, Director of Research, Jerome Levy Forecasting Center

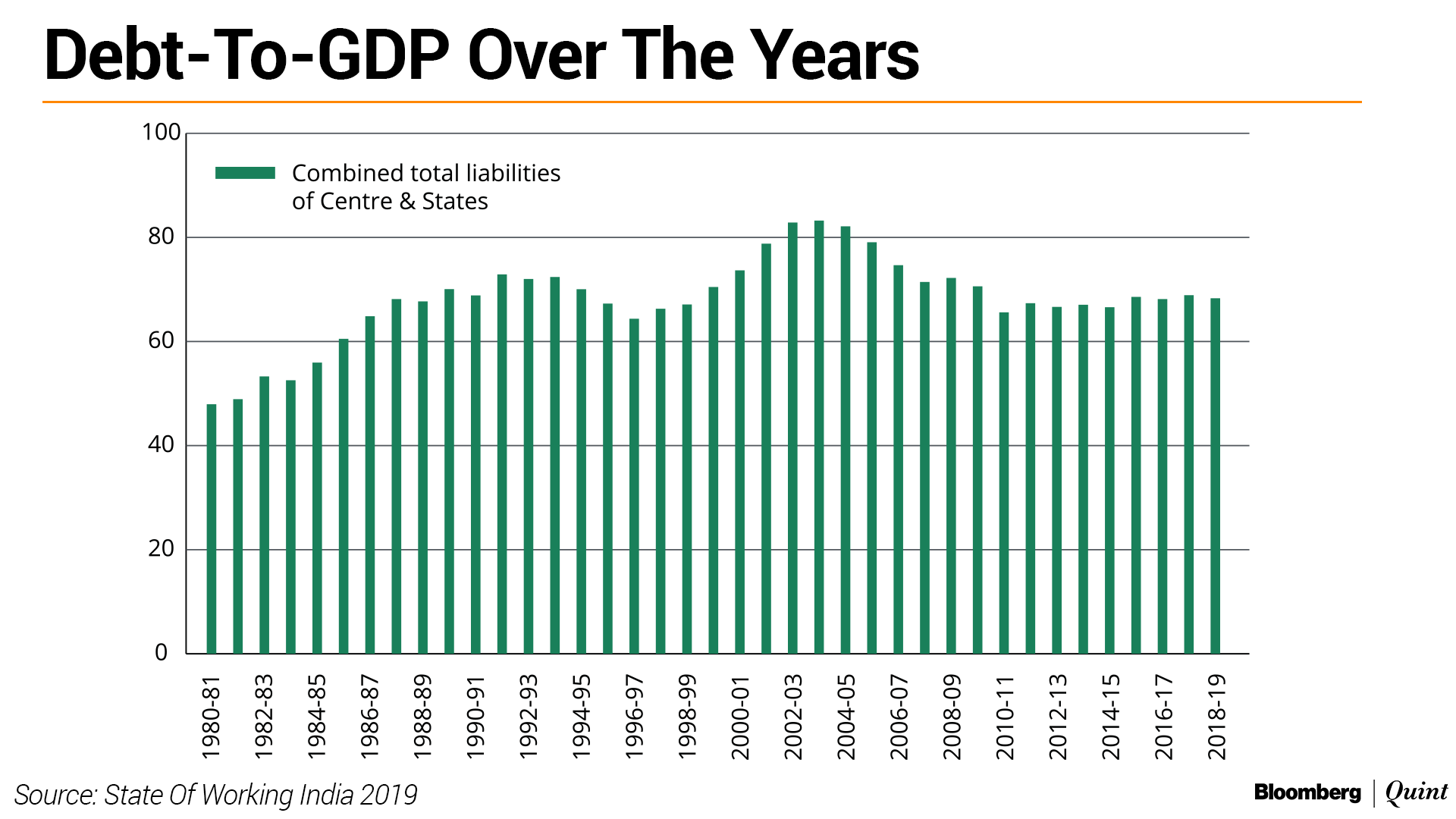

Thiruvadanthai writes that there are major misconceptions about fiscal deficit, government debt, and fiscal sustainability in India's case.

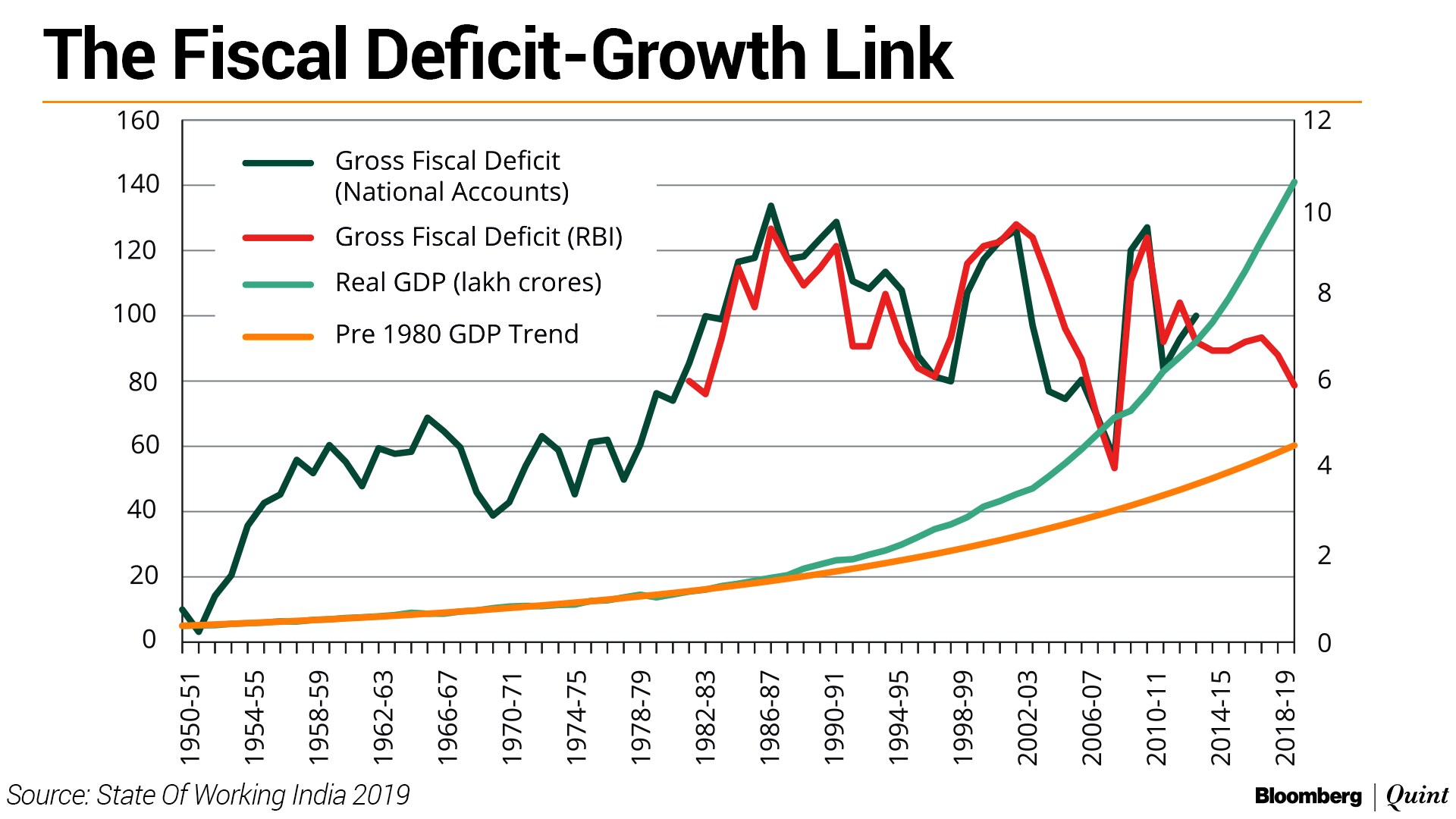

His premise is simple: there is a correlation between higher fiscal deficits and economic growth. "High deficit periods have also been periods of high growth," the paper said.

Thiruvadanthai highlighted a comparison between phases in the Indian economy before 1980 and after that. He noted that since 1980, fiscal deficit has only grown—barring one exception in 2007-08—but that has also coincided with the takeoff in India's gross domestic product.

He said there is widespread agreement among economists that the economic acceleration India saw in the 1980s was due to fiscal expansion. But while most mainstream economists also suggest that these high fiscal deficits were harmful in the long-term leading to the 1991 crisis, Thiruvadanthai says it is an incorrect assessment. He believes the crisis built-up due to an increase in private sector debt rather than fiscal profligacy.

As things stand right now, India has enough scope for fiscal expansion, he argues. The consolidated deficit for 2018-19 is estimated to be 5.9 percent of the GDP, which would be the lowest in the last forty years barring the two economic boom years of 2006-07 and 2007-08 when growth hit double digits.

This tight fiscal policy has restrained growth and added to India's employment strains.

"Fiscal policy has been too tight for a few years, given the deleveraging imperatives of the corporate sector, the balance sheet problems of the banking sector, and the backdrop of weak global growth.”

India's present fiscal policy is too tight.Srinivas Thiruvadanthai, Director of Research, Jerome Levy Forecasting Center

But any government going in for fiscal expansion will face a lot of resistance. “...such a policy will flounder if the bogeyman of fiscal sustainability forever hobbles the fiscal support needed,” Thuruvandathai wrote. “In particular, the obsession with rating agency decisions is pernicious.”

Inflation And Deficits

One common fear for bigger deficits is that it will increase inflationary pressure. “Unquestionably, any policy that boosts demand will tend to push up inflation,” the paper says. But headline inflation is well below the Reserve Bank of India's target range right now. “Moreover, the broader economic context suggests that fiscal deficits are unlikely to result in much higher inflation.”

There are three reasons that Thuruvandathai gives for inflation to remain in check. First is that oil prices are subdued. The second is that food prices, which have a large influence on inflation in India, have been benign.

The third, he writes, is that the strength of feedback from deficits to inflation depends on context. “Running large deficits in the midst of robust private sector activity is likely to result in overheating as supply constraints and bottlenecks become binding,” the paper says. “Currently, there is a capacity glut. For example, capacity utilisation in the manufacturing sector is running well below the early 2011 peak. In short, the conditions that promote rising inflation are currently absent.”

Fiscal Policy For Jobs

Thuruvandathai has outlined four broad steps which the government can use its extra fiscal room to promote jobs growth.

He suggests spending on skill development and facilitating on-job training. “The key to employment generation is to recognise that on-the-job training provides one of the best and most cost-effective ways of imparting occupational skills and enhancing employability.”

Government should subsidise job training programmes making it more likely for businesses to offer such opportunities. It can also look at industry partnerships for college students and those in vocational courses, he said.

The government should also provide necessary financial support to startups at the bottom of the pyramid. In a startup ecosystem which is dominated by “copycats”, Thuruvandathai said the government should incubate startups with innovative solutions to local problems. These find it harder to get funding as they are perceived to be risky by venture capitalists.

Expanding the Mahatama Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act is another way of promoting jobs growth. The paper said that MGNREGA has “multifarious benefits” but the programme has been hampered by inadequate funding. “This is hardly surprising given that the current allocation to MGNREGA is less than 0.3 percent of GDP as opposed to the 1.7 percent that the World Bank estimated the programme would require to be fully funded.”

Lastly, India should increase its efforts in the preservation of its numerous heritage structures and promote tourism. Restoration and maintenance of heritage sites can directly provide employment and boosting tourism provides indirect employment, Thuruvandathai wrote.

“While economic growth has allowed India to bring down poverty rates dramatically, especially extreme poverty, growth has not translated into jobs,” the paper said. “Given India's burgeoning youth population, there is an urgent need to craft a government policy, adequately supported by the budgetary resources, to promote robust employment generation.”

Watch the interview with Thuruvandathai here:

Essential Business Intelligence, Continuous LIVE TV, Sharp Market Insights, Practical Personal Finance Advice and Latest Stories — On NDTV Profit.