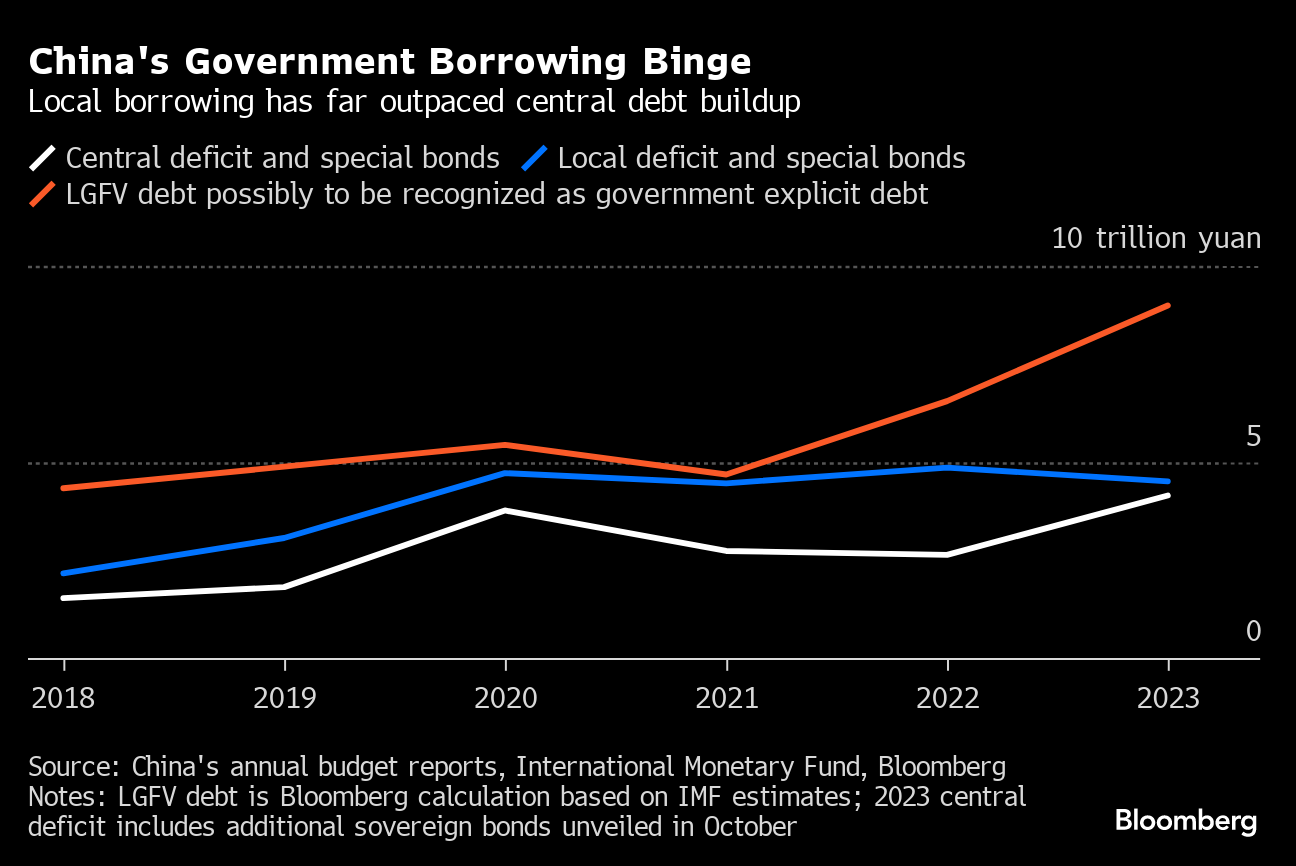

(Bloomberg) -- China's central government is borrowing more to help diffuse a $9.3 trillion time bomb in hidden local debt. The resulting shift in fiscal power has its own risk: demotivating regional officials.

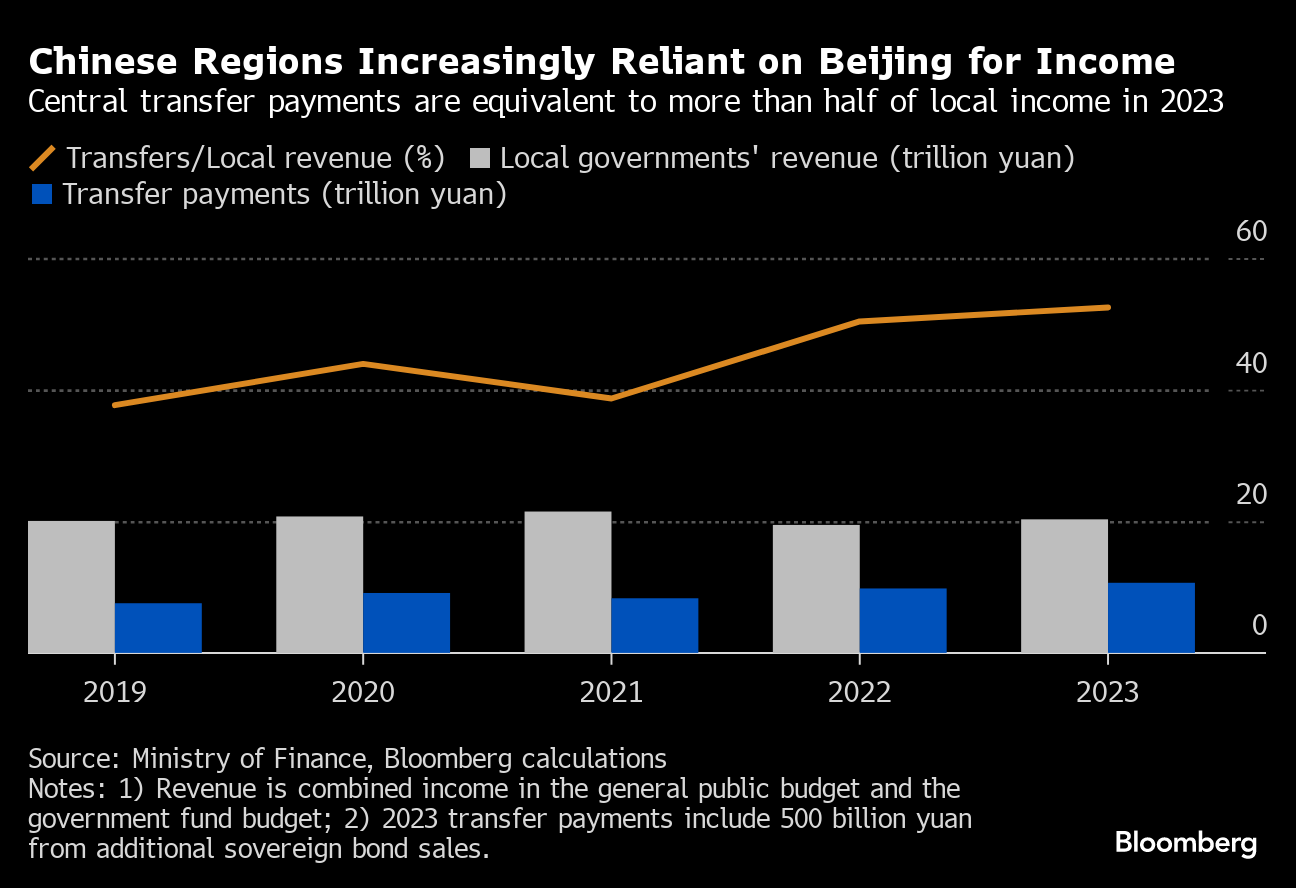

Beijing's rare decision to issue 1 trillion yuan ($137 billion) of central debt, and transfer the funds to local governments, was hailed in October as a relief for struggling provinces.

That move came as China clips the borrowing ability of local authorities, including by banning the creation of the financing vehicles that allowed off-balance debt to spiral.

Some analysts see that strategy as the beginning of a revamp of the inter-government debt structure. The overall result could diminish the fiscal discretion of local leaders and weaken their drive to enact new policies.

“Long-term dependence on the central government will stifle local governments' aspiration to develop the local economy and society in innovative ways,” said Le Xia, chief Asia economist at Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria SA. “That'll do no good to the prosperity of the economy.”

Bureaucratic inaction would make it harder for President Xi Jinping to achieve his goal of growing China into a “medium-developed country” by 2035. Some economists estimate that requires the economy to expand 4.7% on average each year until then — an ambitious target.

Protracted Struggle

The balance of fiscal power has oscillated between the central and local governments for decades. In the mid-1990s, then-Vice Premier Zhu Rongji reined in provinces' ample taxation powers — which had earlier been given as an incentive to develop their economies — in a bid to replenish central coffers.

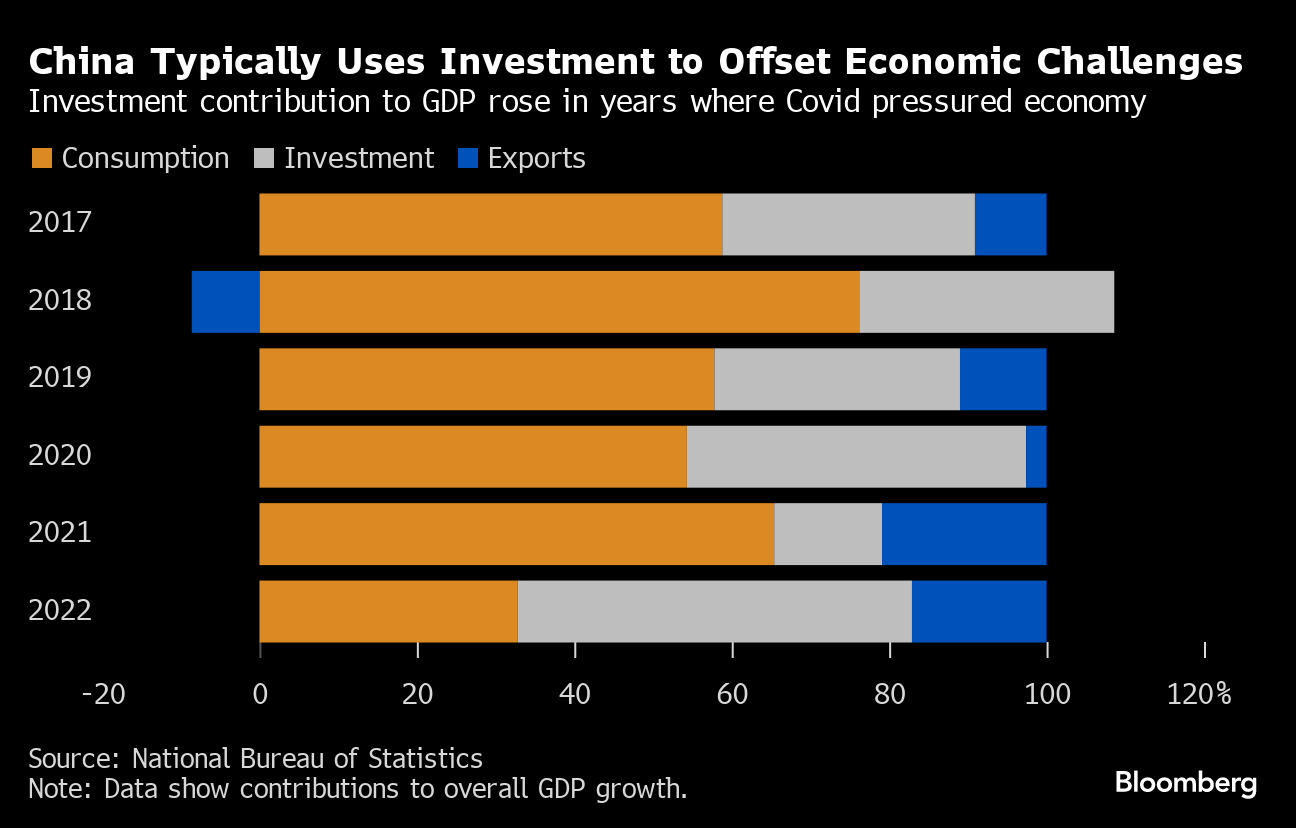

After the global financial crisis hit in 2008, Beijing was forced to pivot, calling on regional officials to fund a massive stimulus program reliant on infrastructure investment. That led to a big increase in off-balance sheet debt by the companies that borrow on behalf of provinces and cities to finance such campaigns.

That growth model has become unsustainable: Local governments can no longer depend on land sales to service their debts — both official and hidden — as the nation's property market crisis deepens. LGFVs in some regions have teetered on the verge of default in recent years.

Swinging the pendulum back in the central government's favor, however, risks stripping agency from local officials who know their economies best. A tendency to do less to avoid making mistakes is already an issue in China's vast bureaucracy as Xi's anti-corruption campaign rolls on.

Last year, then-Premier Li Keqiang warned annual growth risked slipping out of a reasonable range if officials didn't take decisive actions to fix Covid Zero-related problems, such as supply chain blockages.

A county in Lishui city in east China gave three government agencies a “Lying Flat Award” at an official gathering last year, shaming them for administrative inaction, local media reported. Inner Mongolia's agriculture and husbandry department is handing out “Snail Awards” to officials who flunk performance reviews.

Support Needed

Beijing's pledge to unleash more sovereign bonds to fund disaster relief — in effect, an infrastructure spending program — indicated the government's efforts to create more sustainable sources of local income may have stalled.

A national property tax could replace land sales as a major source of local revenue. But that levy is deeply unpopular with the nation's powerful middle class, and weak consumer demand dragging on growth makes it unlikely such a policy will be implemented anytime soon.

Discussions on revamping consumption taxes to allow provinces to take a share have also resulted in little change.

“Reforms to increase the main types of taxes for local governments have hit snags,” said Jia Kang, a former head of a research institute under the Ministry of Finance. “It's currently impossible for the local tax regime to provide a stable source of income for regions to sort out their problems.”

Top leaders at a major annual economic conference last week called for “reform of the fiscal and tax system,” without elaborating. That statement stoked expectations Beijing could be mulling plans to restructure the central-local relationship.

“A key part of the new round of fiscal system reform could be for the central government to bear a larger share of the budget deficit, as well as more spending responsibilities,” said Jacqueline Rong, chief China economist at BNP Paribas SA.

Beijing's increased sway could help it drive through big reforms, previously held back by regional resistance. Bringing provincial pension systems into a national pool, for example, would serve Xi's common prosperity push to narrow the wealth gap.

“The central government can use transfer payments to address uneven developments and fiscal power among regions,” said Ding Shuang, chief economist for Greater China and North Asia at Standard Chartered Plc.

Beijing could also push regional leaders to solve problems such as weak consumer spending at their own expense.

While local governments face enormous cash flow pressures, they still hold assets worth as much as 20% to 30% of China's GDP, according to Michael Pettis, a finance professor at Peking University.

Transferring some of those funds to households, such as by using land to build low-cost housing rather than selling to the highest bidder, would be “the least painful” way to boost consumption and rebalance the economy, he said.

“But these transfers will be politically contentious,” he said. “In the next few years, we can expect a conflict between Beijing and local governments over who will absorb the costs.”

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.

Essential Business Intelligence, Continuous LIVE TV, Sharp Market Insights, Practical Personal Finance Advice and Latest Stories — On NDTV Profit.