The Economic Survey 2016-17, released on Tuesday, has officially kicked off a debate on whether India needs to move towards a Universal Basic Income (UBI).

The Survey advocated the concept of UBI, positing it as an alternative to various social welfare schemes currently running in the country.

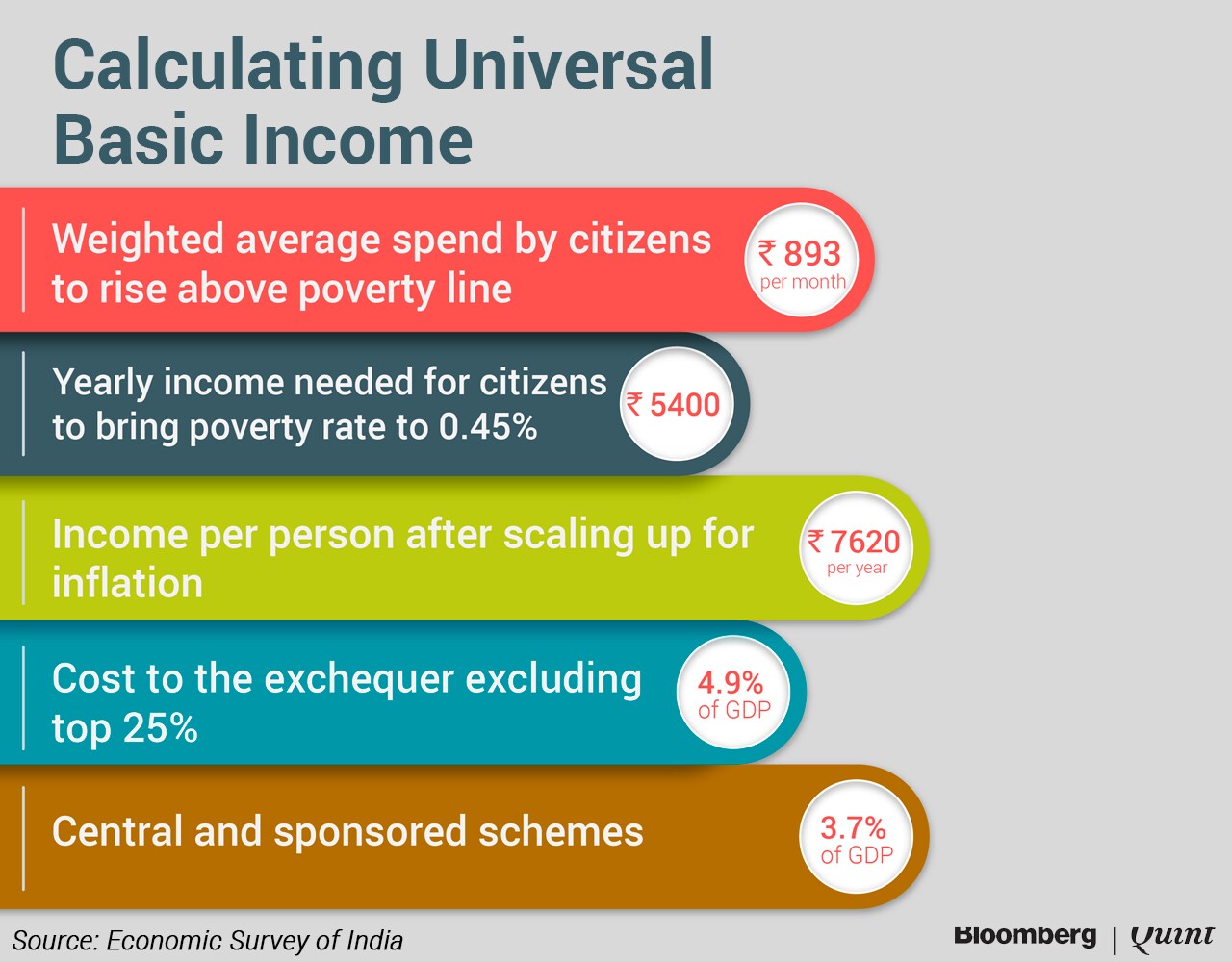

It is a “conceptually appealing idea” but with a number of implementation challenges, the Survey said, pegging the costs -- based on inflation-adjusted poverty line -- at 4-5 percent of the GDP.

UBI should be based on the principles of universality, unconditionality and agency, it said.

It concluded that a more efficient way to help the poor would be to provide them with resources directly through UBI as opposed to allocating resources to various Centre- and state-run schemes where misallocation is a real concern.

UBI should be implemented on a pilot basis, Chief Economic Adviser Arvind Subramanian told reporters at a media briefing, but added that there are limits on how much one can rely on pilot projects.

An Open Debate

Long-time proponents of the concept, like Guy Standing who co-founded the Basic Income Earth Network in the 1980s, argue that existing subsidies should be withdrawn to create fiscal space for cash transfers. A number of other economists have also supported the idea in recent writings, arguing that it is time for India to move in the direction of a universal basic income.

In an interview to BloombergQuint in January, Standing had said that their experiments conducted in 2010 had shown that the effects of UBI can be “transformative”.

Others like development economist Jean Dreze support the concept of a universal income, but he had termed it as “futuristic” in the Indian context in a conversation with BloombergQuint in January. Reetika Khera of the Humanities and Social Sciences Division at the Indian Institute of Technology, Delhi, has argued in favour of a phased approach where existing schemes such as pension for the elderly can be thought of as Universal Basic Income for that segment.

.jpg)

Also Read: Economic Survey: Demonetisation To Pull Growth Down To 6.75-7.5% Next Fiscal

Making Room For A Universal Income

The Indian government has struggled to stick to a path of fiscal prudence and is mandated to bring down the fiscal deficit to 3 percent of the GDP by the next financial year. While there could be some relaxation in the target by a committee on the fiscal road map, the government will need to balance out a number of spending priorities.

It is, then, fair to expect that a basic income concept, if ever implemented, would need to come at the cost of existing social programmes.

The Survey said that it will be fiscally unaffordable if the UBI becomes an “add-on” to the existing social programmes rather than replacing them. It added that a UBI that reduces “poverty to 0.5 percent would cost between 4-5 percent of the GDP, assuming those in the top 25 percent income bracket do not participate”.

This is slightly steeper in fiscal costs as compared to existing middle class subsidies, in addition to food, petroleum and fertiliser subsidies, that cost about 3 percent of GDP.

Batting for UBI, the Survey said that a state can't determine which risks to a person should be mitigated and when. Thus, a regular income could liberate citizens from “paternalistic and clientelistic relationships with the state”.

However, the Survey said it is important to recognise that universal basic income will not diminish the need to build state capacity: it will still have to enhance its capacities to provide a whole range of public goods.

While Aadhaar is designed to solve the identification problem, it cannot, on its own, solve the targeting problem, the Survey added.

India has a myriad schemes and subsidies targeted at the poor. Prominent among these are the employment-providing Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA), the Public Distribution System (PDS), which provides subsidised foodgrain, along with the fertiliser and fuel subsidy schemes. But many of them have been plagued by poor targeting and leakages.

The Survey said there is a need to simplify and rationalise the vast number of programmes run by the central government for welfare. It pointed out that there are 950 central sector and centrally sponsored sub-schemes in the country, accounting for about 5 percent of the GDP.

“Even leaving aside their effectiveness, considerable gains could be achieved in terms of bureaucratic costs and time by replacing many of these schemes with a UBI,” the survey said.

The calculated costs turned out to be 4.9 percent of the GDP for a UBI of Rs 7,620 per year per person for the bottom 75 percent of the population.

The process of determining a UBI amount is not a one-time exercise: as the UBI is a cash transfer, its ‘real' value tends to be determined by inflation in the economy. Over time, the same amount of cash transfer may not buy the same amount of goods.Economic Survey Of India

The survey concluded that UBI is an idea whose time may not be ripe for implementation just yet, but is ripe for a serious discussion.

Essential Business Intelligence, Continuous LIVE TV, Sharp Market Insights, Practical Personal Finance Advice and Latest Stories — On NDTV Profit.