No jam was being made that morning at the Bhuira Jam Factory in this remote Himachal Pradesh village. There was no fruit to be weighed and sorted, cut and boiled. A basket of ripening peaches lay unattended by the weighing scale.

The all-women jam-making team at Bhuira had a new task: Emptying out the office so that it could be painted. Perhaps out of habit, the women had their caps neatly on, their hair firmly tucked in, a smidgen of sindhoor (vermilion) peeping out from beneath.

Seated before a computer, Upasana Kumari is not a jam-maker at all and described herself as an administrator. With a BSc in information technology, the farmer's daughter said all seven of her sisters (plus a brother) are educated or are still studying. The youngest wants to be a doctor and is in her final year of school; the eldest is married and helps her husband with his fruit orchard. “Only I have a paid job,” pointed out Kumari.

Married to a policeman who has a secure job and a steady salary, Kumari said she thought about getting back to work now that her only child, a boy, is three. What started with part-time work is now a full-fledged job, and she's grateful for the factory since there aren't many job opportunities for someone with her qualifications in this remote area. “If it wasn't for this factory, I wouldn't have been able to work at all,” she said. “I didn't study so much so that I could sit at home.”

In contrast to its neighbours–particularly Punjab, Uttar Pradesh and Haryana–Himachal Pradesh stands out as a positive outlier in terms of social development.

Higher Sex-Ratio At Birth, More Literate And Educated Women

The 2011 Indian Human Development Report ranked Himachal Pradesh third after Kerala and Delhi. Dramatic poverty decline in rural areas–where 90 percent of the population lives–from 36.8 percent to 8.5 percent between 1993-94 and 2011; land reform with 80 percent of the population owning some amount of land; exceptional infrastructure; enlightened policy and legislation (the Himalayan state was the first to ban plastic bags) and an engaged citizenry are some of the features that make this such a stand-out state, according to a 2015 World Bank Group study, Scaling the Heights: Social Inclusion and Sustainable Development in Himachal Pradesh.

But impressive as these features are, the one feature that is perhaps not commented upon enough is the enthusiastic participation of the state's women in jobs, particularly in rural areas.

For some years now, economists and policy-makers have been troubled by the dwindling number of women in paid jobs, or female labor force participation (FLFP).

The data are indisputable. Between the years 2004-05 and 2011-12, 19.6 million women dropped out of the Indian labour force, according to a 2017 World Bank report, Precarious Drop: Reassessing Patterns of Female Labour Force Participation in India.

During 1993-94 to 2011-12, participation fell from 42.6 percent to 31.2 percent. But the sharpest drop occurred between 2004-05 and 2011-12 in rural India amongst young girls and women aged between 15 and 24.

The exception to this trend: Himachal Pradesh.

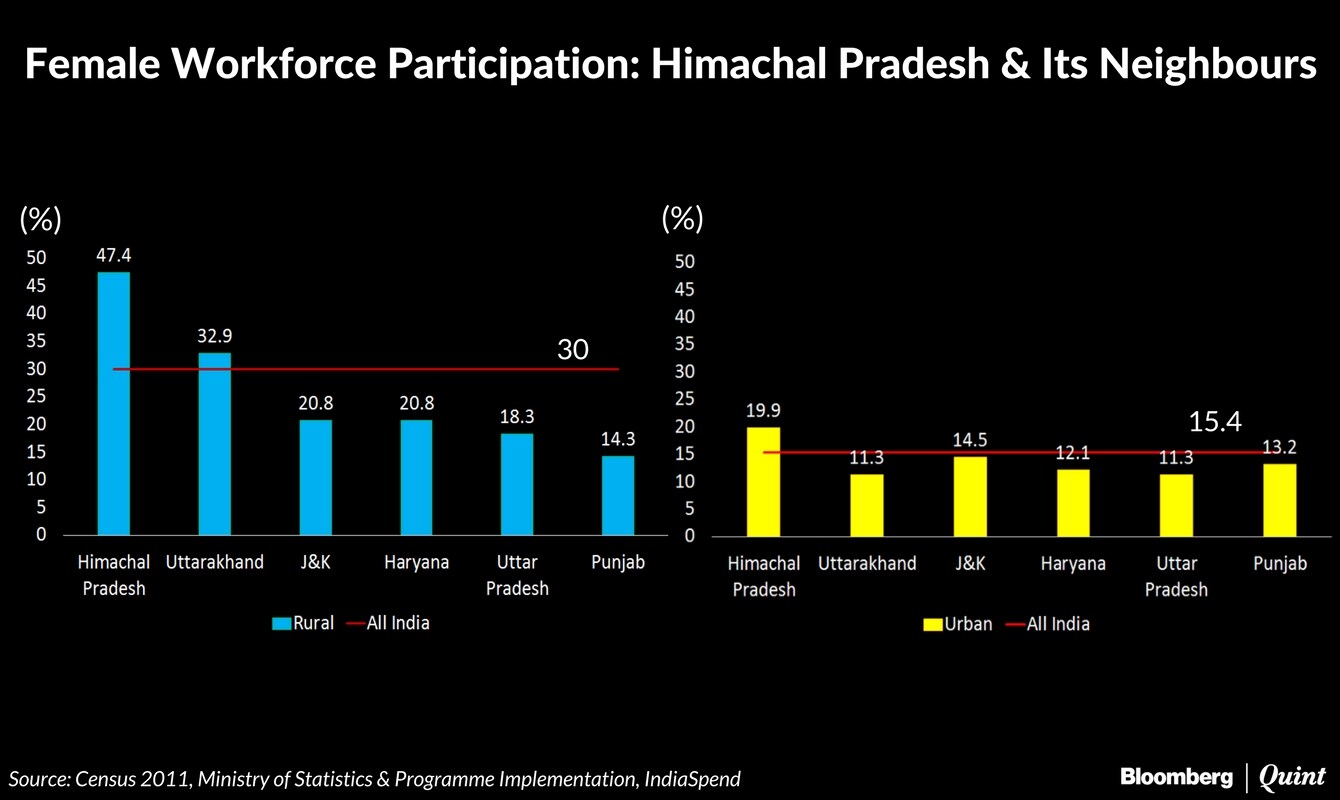

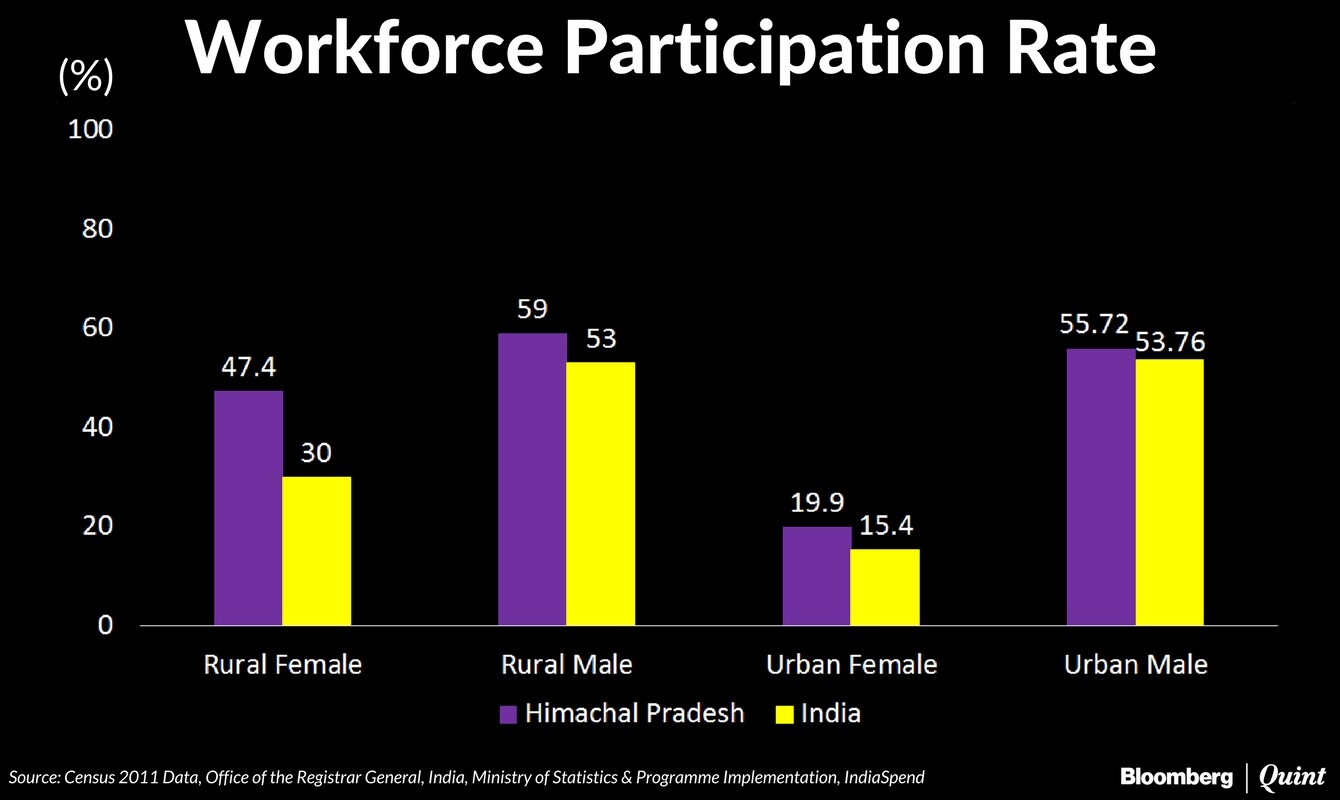

Amongst all states, Himachal Pradesh has, at 47.4 percent, the second-largest participation of women in the labour force in rural areas, after Sikkim, according to Census 2011. More recent findings by the World Bank in June 2017 place the state at number one, at par with Sikkim.

More Women In Rural Himachal Pradesh Are At Work

In keeping with the trends elsewhere the country, FLFP is waning in Himachal Pradesh too. Rural participation dipped four percentage points from 71 percent to 67 percent between 2004-05 and 2011-12, while urban participation also fell from 36 percent to 30 percent, according to this 2015 World Bank Group report.

Much of the state's female workforce participation is driven by agriculture, still the mainstay of the state's largely rural economy. In urban areas, the picture isn't quite so rosy with an FLFP (according to Census data) of 19.9 percent – not great when you compare it with the rural figure, but still higher than the all India urban FLFP at 15.4 percent.

“Women in rural areas are more than twice as likely as their male counterparts to report themselves as being self-employed in agriculture,” said Maitreyi Bordia Das, lead author of the World Bank Group's 2015 study.

Women in the hill states have always worked, said Pronab Sen, country director of International Growth Centre's India central division. “There is a long history of men migrating for jobs and women taking over the economic activity in villages. They take the decisions and call the shots. This is culturally embedded in these states,” he said.

Women's participation in agriculture in the state is probably very different from that in other north Indian states, said Das. Horticulture and floriculture, for instance, have higher value than traditional crops.

But, she warned, women elsewhere in India are withdrawing from agriculture. If Himachal is to avoid this trend, then “it's important to make sure new opportunities in agri business benefit women as well”, she said.

Moreover, pointed out Das, agriculture is arduous manual work. “Himachali women report themselves as being employed in agriculture. This is good in a sense. It means they don't regard themselves as mere helpers but active agents. But to keep them in jobs, it's important to make jobs worth their while. And so, employment in high-value agriculture is really important.”

“I make the rotis, he makes the vegetables.” Neelam Devi, grade X pass

‘Made by happy mountain women,' states every jar that bears the Bhuira label. Last year, these happy women made 65,458 kg of jams, jellies and chutneys sold in 108,000 large and 54,955 small bottles made in two factory units, one at Bhuira and a newer one that was set up in 2011 at Halonipul village nearby.

That's a lot of jam for what started as a personal, for friends-and-family only venture by Linnet Mushran, an Englishwoman who made India her home.

The charming stone-and-slate cottage in Bhuira, Rajgarh tehsil in Sirmaur district, nestled deep inside pine forests in Himachal Pradesh remains Mushran's home and is also the site of the factory that has eight full-time employees, all women, and, in season, between 18 and 19 jam-makers and between 12 and 15 packers (again, all women). Mushran's daughter-in-law, Rebecca Vaz, is helping expand the business.

On the morning that I visited, I ran into Poonam Kanwar, 50, orchard owner who had walked to the factory to inquire if there is a requirement for the apricot and peaches that have ripened on her trees in Chichdiya village close by.

The factory had met this year's orders. Kanwar shrugged–there would be other sales, figured the woman who has been supplying fruit to the jam factory for 10 years. Selling fruit to be made into jam anyway is an added source of income–her best pickings are sold in mandis and then sent to fruit markets in Delhi.

There's really no time for chit-chat. Kanwar tends to 150 fruits trees, including lemons and pears in addition to peaches and apricots. She also grows vegetables for her own consumption. And there are four cows to look after.

The hard work of tending to the land and all that thrives on it is shared by Kanwar and her husband, ‘fifty-fifty', she said.

A son has completed his masters in technology and has a job, and her 28-year-old daughter, as yet unmarried, is a ‘PhD in computers', she said proudly. “I have worked on the land from the day I got married,” said Kanwar. “But nowadays girls are educated and when that happens there is no question that they will do farming.” Kanwar's daughter has a job, teaching in Chandigarh where she lives alone.

The idea of shared household work doesn't seem to be a novelty for many of the women. Neelam Devi, a grade X pass, has worked on and off at the factory–breaks in employment marked by the birth of her three children.

“Before marriage also I used to work. But then it was for shauk (fun). Now I earn so that I can educate my children, send them to the best schools, let them study to their heart's content,” said Neelam Devi. It's a vision she shares with her husband. “If he didn't help me at home, how could I have worked outside? I make the rotis, he makes the vegetables,” she said.

Women in Himachal Pradesh have a long and perhaps unique history of community activism, pointed out Das's World Bank report. “This form of assertion in public spaces resonates with their agency in the private sphere,” it stated.

As many as 96.4 percent of married urban women and 90 percent of married rural women in Himachal Pradesh–well above the all-India average of 85.8 percent and 83 percent, respectively–reported participating in household decisions, according to the National Family Health Survey, 2015-16.

Kamla Devi is the 58-year-old pradhan (head of the village council) of Bhuira village (population 685). She is, unusual for India, the only child and therefore the sole inheritor of her father's land. “I grew up here. I am a daughter of this village,” she said.

The widow of a soldier, Devi has lived all over India including Kerala and Sikkim. “On the times that I went with him, I hired casual labour to look after the fields and fruit trees,” she said. Of her two sons, the elder died of cancer and the younger has a small tent business. Now, she tends to the fields alone, and looks after village council work. There's a government school up to the grade X and two anganwadis (courtyard shelters). “Every girl here is in school,” she said.

I am introduced to Devi by her elder daughter-in-law, Ranjita, who has worked with Bhuira Jams from the day it received its commercial license in 1999. Back then, she was a young woman. Now, with her husband dead and nobody to help her mother-in-law with the land, was it ever suggested to her that she might perhaps chip in? “No. Never. I have always worked. The question of giving up my job never arose,” she said.

Bhuira's grand supervisor is the four-feet-something Ram Kali, a woman with an easy laugh who says her age is between ‘50 and 65' depending on her mood.

Kali's parents came to Himachal Pradesh as migrant labour. She has no idea when they went back, or why she was left behind with a Himachali family. But this state has been her home ever since. She first came to Bhuira with her husband, a daily wage laborer who died some years ago, as a tenant farmer. “It was a forest. We leveled the land, planted apple trees and potatoes and lived on it for free,” she said.

For a woman who has never been to school, Kali manages the day-to-day operations at the jam factory–how much fruit is needed, is there enough stock and does lunch have to be cooked for the occasional visitor–with aplomb. “She's my boss,” laughed Vaz.

This factory has changed so many lives,” she said. Having a job has meant empowerment in tangible ways. Everyone, even the temporary employees, has a bank account and post office savings schemes. Even those who don't work here, like fruit-supplier Poonam Kanwar, have an additional income for the fruit that doesn't make it to markets in Delhi and would otherwise rot on the trees.

“In Himachal, nobody ever went hungry,” said Kali. “But nobody ever had cash. Now, every woman here has money in her pocket.”

This is the sixth in a nation-wide IndiaSpend investigation into why Indian women are dropping out of the workplace.

(Namita Bhandare is a Delhi-based journalist who writes frequently on gender issues confronting India.)

This article has been published in arrangement with IndiaSpend.

Essential Business Intelligence, Continuous LIVE TV, Sharp Market Insights, Practical Personal Finance Advice and Latest Stories — On NDTV Profit.