(Bloomberg) -- US efforts to promote the expansion of India's solar industry may have opened a back door to components made with forced labor in China.

India's largest solar producer, Waaree Energies Ltd., has sent millions of panels to the US with components from a Chinese company whose products were repeatedly denied entry to the US market over concerns about forced labor, a Bloomberg News examination of Indian and US import records shows. Those components, solar cells produced by China's Longi Green Energy Technology Co. at plants in Malaysia and Vietnam, are used in Waaree panels blanketing solar farms in Texas and other states.

Imports of Waaree panels raise questions about how US Customs and Border Protection officials are enforcing a ban on products tied to the repression of Uyghur people in China's Xinjiang region. The agency has detained thousands of shipments of solar panels made by Chinese-owned companies since it began enforcing the ban in June 2022 — interventions that companies can overturn by providing evidence their supply chains don't involve Xinjiang sources.

That focus on China has created an opportunity for Indian solar producers, which exported almost $2 billion worth of panels to the US in the first 11 months of last year, a fivefold increase over all of 2022, according to data compiled by BloombergNEF.

“Even panels that say, ‘Made in India' are likely to be affected by Uyghur forced labor,” Laura Murphy, co-author of an August 2023 report about the solar supply chain, said in October before being named a Customs enforcement adviser at the Department of Homeland Security. Her report said that because polysilicon from multiple sources in China is often blended together, there's a “very high” risk that panels made at Longi factories in Southeast Asia had used at least some materials from Xinjiang.

Longi, the world's largest solar producer, based in Xi'an, China, didn't respond to requests for comment. The company has said, in response to Murphy's report, that it has created a separate supply chain for the US market that uses material only from non-Chinese sources.

Sunil Rathi, Waaree's sales director, said in an emailed statement that the Indian firm “has been complying with the law of the land wherever we operate.” He said its customers “have stringent requirements, and they make sure we meet those for every shipment.”

Global concerns that Chinese officials were incarcerating or forcing members of the Uyghur minority to work in factories led Congress to enact the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act, known as UFLPA, in December 2021. The Chinese government has denied any human rights violations in Xinjiang, saying its policies there are aimed at education, eradicating extremism and alleviating poverty.

Some members of Congress and industry groups have criticized Customs for uneven enforcement of the law, which covers a range of products from tomatoes to shoes. At least 16 members of the US House or Senate have written to the Department of Homeland Security requesting stricter enforcement. The latest, in January, from representatives Mike Gallagher, a Wisconsin Republican who chairs the Select Committee on the Chinese Communist Party, and ranking member Raja Krishnamoorthi, an Illinois Democrat, cited “a failure to fully prosecute or otherwise deter transshipment of forced labor goods through third countries.”

The value of apparel and textiles detained for inspection by Customs in the first seven months of 2023 dropped 52% from the previous seven months, according to the National Council of Textile Organizations, which analyzed data from the agency. At the same time, the value of intercepted electronics shipments rose 6%.

A spokesperson for Customs said the bureau “employs a dynamic, risk-based approach to enforcement that prioritizes action against the highest-risk goods based on a dynamic data and intelligence environment.”

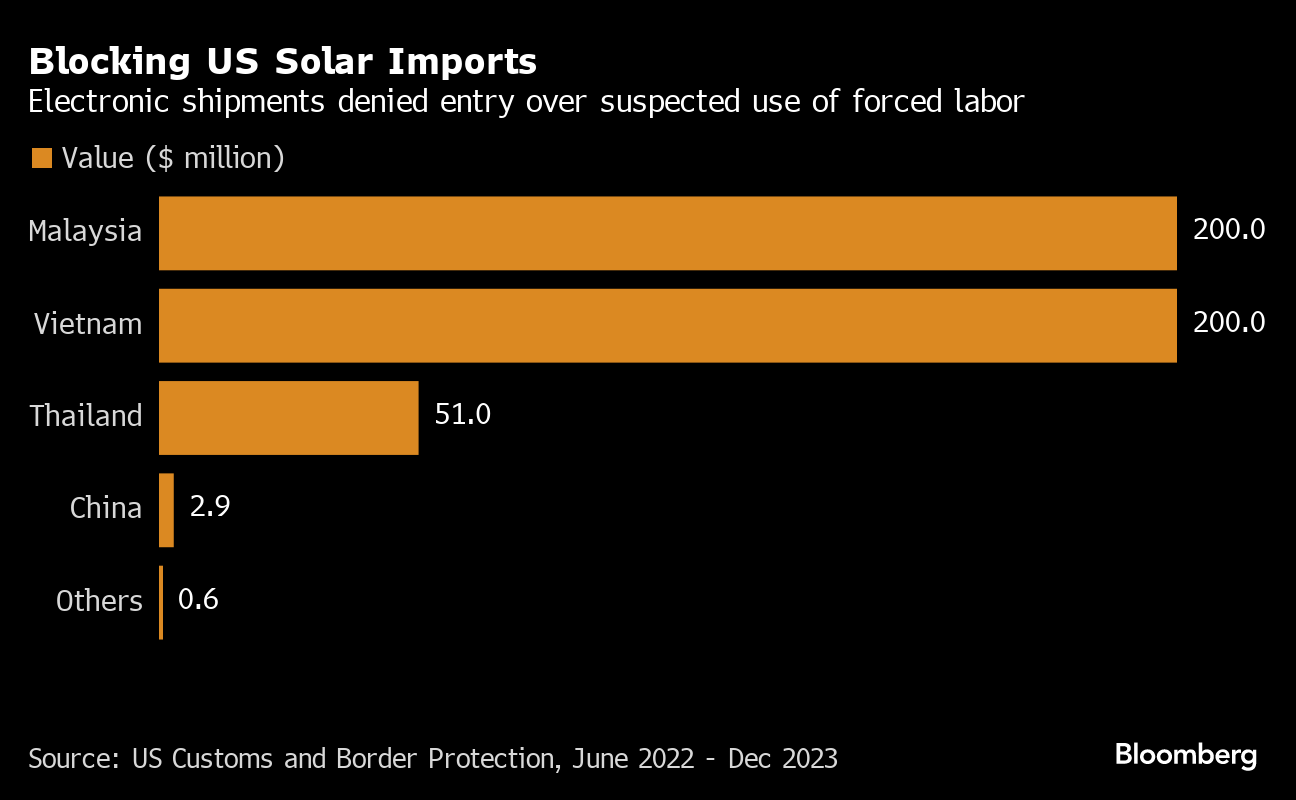

The bureau's website shows that since June 2022 Customs has detained $2 billion worth of products categorized as electronics, which industry analysts say are primarily solar panels. After reviewing supply-chain documents, officials barred about one-quarter of the total for violating the UFLPA.

Customs doesn't identify the companies affected by these actions, which took place even as US imports of solar products reached a record high last year. The agency's data show that US officials have concentrated enforcement efforts on solar products from Southeast Asia, where Chinese companies including Longi shifted production a decade ago in part to avoid US tariffs.

Longi has acknowledged the impact. In a September earnings call, Chairman Zhong Baoshen cited “a massive impairment” as a result of Customs officials denying US entry for its products. “Since they cannot enter the United States, we need to process the returns of these products and resell them globally,” he said.

Since then, some Longi shipments have been getting through, Philip Shen, an analyst at investment bank Roth Capital Partners, wrote in an October note, suggesting that the company was making progress in its efforts to establish a US supply chain that doesn't rely on Chinese polysilicon.

No shipments from Indian companies are known to have been detained, according to Pol Lezcano, a solar industry analyst at BloombergNEF.

“It's hypocritical, and it's targeted at the big Chinese companies,” Lezcano said of US enforcement. “If you are a big, China-headquartered company, the likelihood your shipment gets detained at the border is higher.”

Indian products made up 9.3% of the volume of US solar imports in the first 11 months of last year, up from 1.9% in all of 2022, according to BNEF data. Imports jumped to 4.4 gigawatts — or about 11 million panels — in the first 11 months of 2023, up from 0.6 gigawatts in 2022, the data show. Most of that came from Waaree.

China produces more than 80% of the world's polysilicon, which is used to make solar panels, and Chinese companies make roughly 98% of all ingots and wafers. About one-third of China's polysilicon capacity is in Xinjiang, according to BNEF, compared with 54% of production before the ban. But there isn't enough non-Chinese polysilicon to meet the demand, meaning some producers need to source polysilicon from China, Lezcano said.

“CBP doesn't have the resources or capacity to fully implement” the Xinjiang imports ban, said Shannon O'Neil, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations in New York who has written about global supply chains. “It has had to pick and choose cases, and in the choosing of cases, it sure looks like geopolitics is in play.”

The Biden administration has been trying to foster alternative supply chains in countries considered allies, a policy it calls friendshoring, to counter Chinese manufacturing dominance. On a visit to India in 2022, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen spoke about US support for India's solar manufacturing industry, including $500 million in debt financing for the largest US solar maker's plans to open a plant there. She cited the need to diversify away from China, where solar materials “like those from the Xinjiang region are known to be produced with forced labor.”

The US first banned polysilicon from Xinjiang in 2021, when it was placed on list of goods deemed to have been produced by forced labor. The US began enforcing the UFLPA the following year. Under that law, US officials apply what's called a “rebuttable presumption” that products linked to Xinjiang were made with forced labor.

Importers can challenge that determination by supplying documentation showing their supply chains don't rely on polysilicon from Xinjiang. But polysilicon has been co-mingled with material from other parts of China, making such proof difficult.

The polysilicon production process entails mining quartz, then crushing and heating it to produce metallurgical grade silicon, known as MGS. That material is refined into polysilicon, which is melted into ingots, then turned into wafers and ultimately solar cells that make up solar panels.

MGS and polysilicon from different Chinese locations are often blended, which could introduce Xinjiang-sourced material “into any batch made by a company sourcing any amount” of it from the region, according to “Over-Exposed,” the report by Murphy, who is also a professor at Sheffield Hallam University in the UK, and solar consultant Alan Crawford.

A 2021 US State Department advisory cited evidence of coercive labor practices at each stage in China's solar supply chain. “The pervasiveness of forced labor programs in Xinjiang and co-mingling of solar-grade polysilicon supplies by downstream manufacturers raise concerns throughout the entire solar supply chain,” the advisory said. As a result, it's likely that “the majority of global solar products may continue to have a connection to forced labor.”

Industry analysts draw similar conclusions. “We believe, based on our ongoing industry research, that smaller solar module manufacturers outside of China, including in India and Southeast Asia, are using material inputs from China that are possibly, and in some cases likely, exposed to forced labor while continuing to export to the US,” said Reginald Smith, a solar industry analyst at Eventide Asset Management in Boston.

The “Over-Exposed” report compiled publicly available records, corporate annual reports, press releases, customs data, email exchanges with companies and other sources.

The report included a supply-chain map showing links between Xinjiang-sourced polysilicon and Longi's factories in Southeast Asia. But a rebuttal map provided by Longi and included in the report said the company had created a separate supply chain for the US that uses polysilicon only from non-Chinese sources.

Neither that claim nor Murphy's could be independently confirmed. But Longi modules containing polysilicon produced in China were among those that Customs officials denied entry to the US market, according to a July note by Roth Capital's Shen. Modules containing polysilicon from other sources may have been among Longi shipments that US authorities later released, Roth wrote in another note in September.

Indian customs records compiled by trade data aggregator ImportGenius and reviewed by Bloomberg show that Waaree has received hundreds of shipments of solar cells, which convert light into electrical energy for solar panels, from Longi-owned plants in Malaysia and Vietnam since mid-2022.

India, which has limited capacity to produce its own solar inputs, has ambitious plans to build a vertically integrated manufacturing industry to take advantage of opportunities in the US market and at home. Waaree has three plants in Gujarat, the home state of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, and has announced plans to tap government incentives and expand production capacity over the next two years, as well as to develop its own solar cell and wafer manufacturing. It is planning to open a plant near Houston later this year and is seeking approval for an initial public offering to raise as much as 30 billion rupees ($362 million).

Longi also has plans to manufacture in the US. It recently started module production at a facility in Ohio, a venture with Chicago-based renewables firm Invenergy.

Waaree products have been shipped to residential and commercial solar providers in California, North Carolina and Texas, including the Red-Tailed Hawk and Danish Fields solar farms near Houston, US import records show. Neither project responded to requests for comment, and it couldn't be confirmed independently whether the components of those panels were made with materials from Xinjiang.

India is poised to further expand its US solar market share this year, when anti-dumping and countervailing duty tariffs on solar products from Southeast Asia come into effect in June.

Eric Choy, the top Customs official in charge of UFLPA enforcement, said at a June webinar organized by risk-intelligence firm Kharon that third-country risk “is probably the highest risk that's out there.”

--With assistance from Rajesh Kumar Singh and Zachary R. Mider.

(Adds details about congressional letters to Homeland Security in 9th paragraph. A previous version of this story corrected spelling of Malaysia in chart.)

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.

Essential Business Intelligence, Continuous LIVE TV, Sharp Market Insights, Practical Personal Finance Advice and Latest Stories — On NDTV Profit.