Private Credit Isn’t As Risky As Some May Believe

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The rapid rise of funds that make loans directly to buyout deals and other highly indebted companies — known as private credit — is among the hottest topics in finance. The sector has minted fresh billionaires, while being called a bubble by traditional financiers like UBS Group AG Chairman Colm Kelleher and attracting warnings about the dangers it could pose.

Investors need to be sharp-eyed about what private credit managers are doing with their money. This is, after all, high-yield, high-risk debt. The mad scramble for new business could easily lead to many bad lending decisions, as it always has in the history of banking. But fears that private credit could threaten the financial system should be more soberly assessed. The structure of most private credit funds answers many of the questions about panics and runs posed by the 2008 meltdown because they typically fund their lending with long-term liabilities that can’t easily take flight.

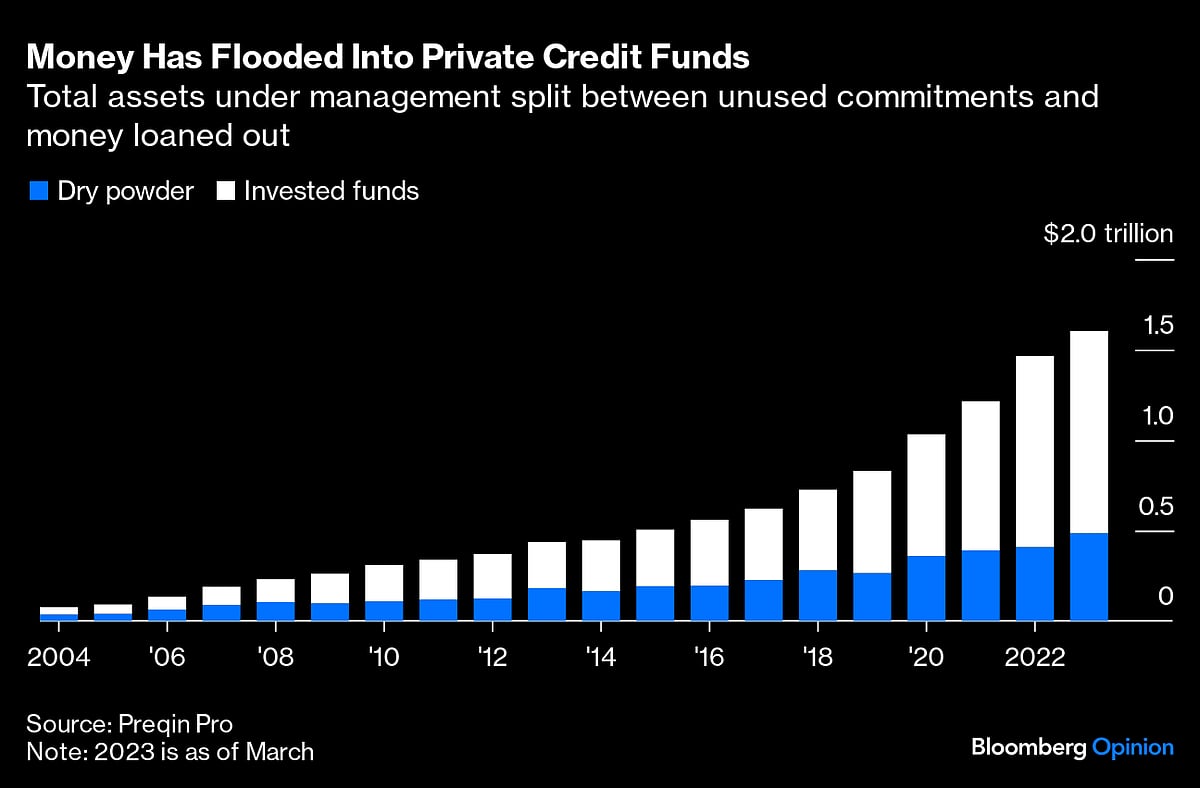

Interest in private credit managers has ballooned as the money has flooded in, while their lending approach brought advantages over traditional buyout funding, particularly this year. Total assets under management in the sector have nearly doubled since 2019 to more than $1.6 trillion, according to Preqin Pro, a data provider. Scale has led to ever-larger individual loans, like this month’s record $4.9 billion for online classifieds company Adevinta ASA.

This year, private equity deal makers have struggled to raise debt through leveraged loans arranged by banks or junk bonds, opening more doors for private credit fund managers. Bond investors lost appetite for high-yield debt, while big banks have demanded extra pricing flexibility when underwriting buyout loans to protect against getting stuck with unsellable debt, like the $13 billion that helped fund Elon Musk’s purchase of Twitter, now named X, last year.

By contrast, private credit managers have been able to offer more certainty to private equity firms trying to finance takeovers because they set the price themselves and keep the loans rather than trying to sell them later.

The funds can take a longer view partly because of how they raise their money. Most private credit is backed by big institutional investors, like insurers or pension providers, which agree to lock up their money for years at a time. If there is a panic, they can’t just ask for their cash back like depositors in a bank. That means the fund won’t need to try to pull the rug from under its borrowers or sell their loans quickly, and it won’t collapse if it suddenly became unable to refund investors.

In short, private credit shouldn’t ever create the kind of systemic risk unleashed in 2008 — the funds shouldn’t suffer runs or fall into spirals of asset fire sales and losses, such as those that periodically engulf banks.

As ever in finance, some are exploring innovations that could undermine these good characteristics. One troubling trend is efforts to sell such funds to the ordinary investing public, who typically require some ability to pull cash early. Bad idea. Late last year, a Blackstone private credit fund for reasonably affluent individuals hit quarterly withdrawal limits as investors looked to reduce risks and book early profits. The fund restricts redemptions to a maximum of 5% of assets a quarter, so it’s still vastly more stable than a deposit-funded bank. However, growing competition for retail money could be a slippery slope toward looser terms.

Some funds also borrow money to increase their lending power and juice returns, which could cause havoc if the lending banks get cold feet and demand repayment.

A greater danger could come from one of the biggest investors in such funds: insurers that sell long-term savings products known as annuities. People can cash in early in some cases. They’ll pay a penalty, but the costs might seem worthwhile if they’re worried about their savings’ exposure to private loans or other risky, illiquid assets. The risk of a large-scale run on annuity businesses has a slim probability but could be extremely damaging to the financial system: A recent Bloomberg editorial sounded a warning about some insurers’ more aggressive investment styles and closer ties with big alternative asset managers.

Regulators in the US and elsewhere need to keep a close eye on these trends. Justifiably, they are demanding more transparency from the sector. But that doesn’t detract from the fundamental stability of having investors locked in for the long term in private credit funds. Even with a big wave of bankruptcies or debt defaults, this characteristic should keep the losses contained.

More From Bloomberg Opinion:

- Private Equity's Bubble Vintage May Fizzle: Chris Bryant

- What If Lending to Your Own Buyout Gets Sticky?: Chris Hughes

- The Private Equity Machine Will Be Tough to Unjam: Paul J. Davies

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Paul J. Davies is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering banking and finance. Previously, he was a reporter for the Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times.

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com/opinion

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.