India never really recovered from the global financial crisis of 2008-09 and the current slowdown is only an extended fallout of the problems that arrived with it, according to a new paper co-authored by Arvind Subramanian.

India's economy has been weighed down by structural and cyclical factors, with finance as the distinctive, unifying element, Subramanian, former chief economic adviser; and Josh Felman, former India office head for the International Monetary Fund, said in the paper—‘India's growth slowdown: what happened? What's the way out?'

Monetary policy and fiscal measures won't be enough and there's a need, among other things, for continuing the asset quality review, shrinking public sector banks and ensuring integrity of data, they wrote.

India is suffering from a balance sheet crisis that has arrived in two waves, according to the paper published by the Center for International Development at Harvard University. The twin balance sheet crisis encompassing banks and infrastructure companies that came after the global financial crisis. And more recently, the four balance sheet challenge—the original two sectors plus non-bank lenders and real estate companies, the paper said.

The nation's growth slipped further in the quarter-ended September to a six-year low amid slowing consumption and a liquidity crisis that started with the defaults of IL&FS group in September 2018. Consumer goods and investment goods production contracted and indicators of exports, imports, and government revenues are all close to the negative territory.

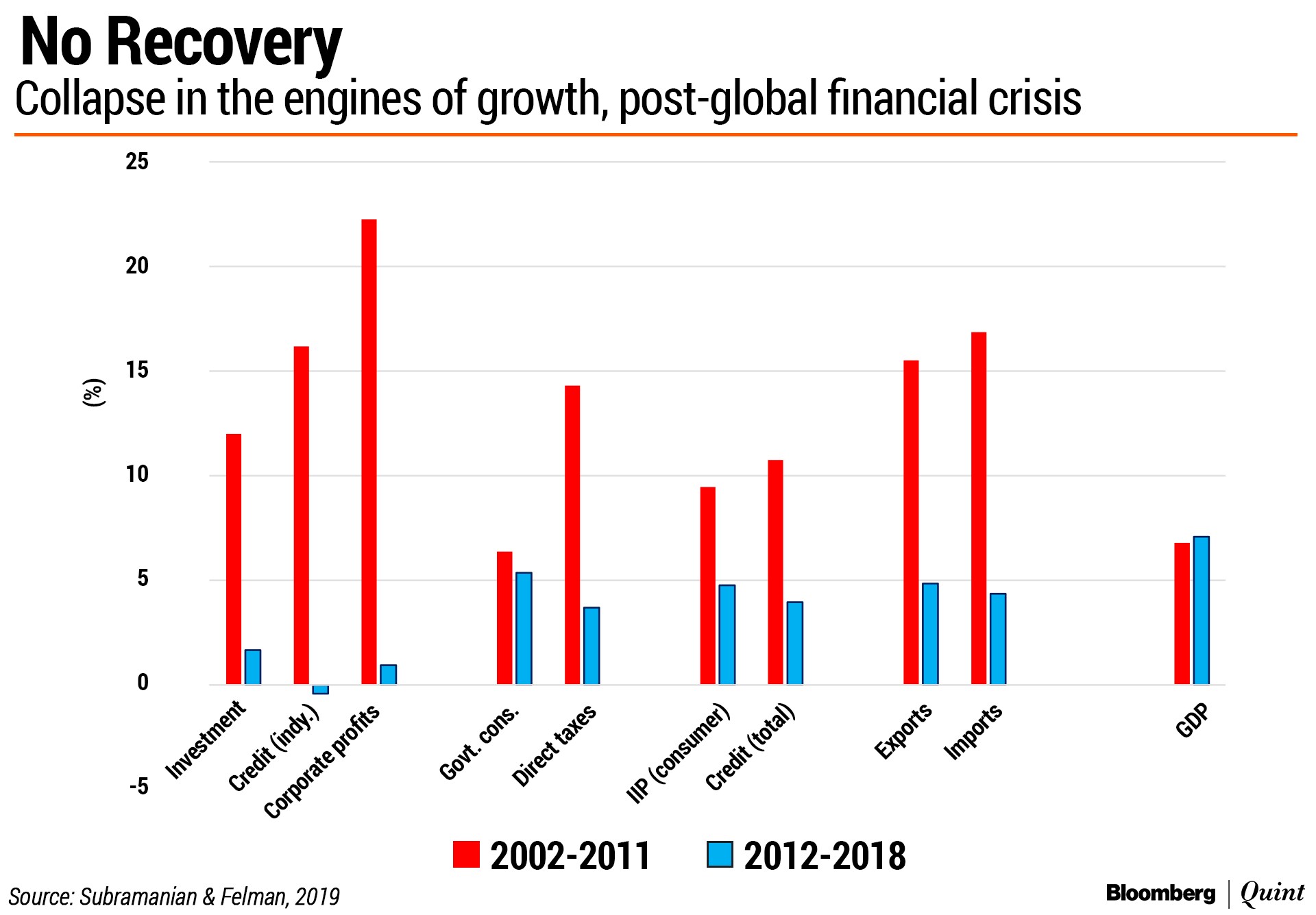

Prior to the last global financial crisis, according to Subramanian and Josh Felman, India's exports boomed, growing at their fastest rates since independence. Infrastructure investments, too, climbed 11 percentage points within four years to reaching 38 percent of the GDP. Accompanying the investment boom, within three years, non-food credit doubled and in 2007-08 alone capital inflows exceeded 9 percent of the GDP.

After the global financial crisis, slower growth, higher interest rates and depreciated exchange rates led to corporate profits collapsing. Corporate debt mounted and non-performing assets soared creating the twin balance sheet crisis. Two of India's growth engines, investments and exports, collapsed, the paper said.

So far, bad loans remain elevated and recoveries under the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code are slower than envisaged, it said.

But economic growth was stimulated by three cyclical factors—rising non-oil export growth in 2017 and 2018, higher off-budget spending and the NBFC lending boom. The end of this credit boom has caused all major engines of growth, including consumption to collapse, according to Subramanian and Felman.

The IL&FS crisis revealed that much of the NBFC lending was channeled to real estate and the sector has seen demand dwindle and unsold inventory remains high, they wrote. In some ways, this may have been India's version of the U.S. housing bubble, according to the paper, and already vulnerable banks worry that the buffer will be far from adequate. High rates and little credit have pushed the economy into a downward spiral, it said.

The two economists cited the difference between lending rates and nominal growth as a stress indicator. In July-September 2019, the weighted average lending rate was 10.4 percent, well above the nominal GDP growth rate of 6.1 percent. As a result, the differential reached 4.3 percent.

“Indeed, the economy seems locked in a downward spiral. Best capturing this stark reality is the astonishingly high interest-growth differential. The corporate cost of borrowing now exceeds the GDP growth rate by more than 4 percentage points, meaning that interest on debt is accumulating far faster than the revenues that companies are generating.”

Why Monetary Or Fiscal Policy Isn't Enough

Subramanian and Felman called the slowdown a combination of structural or cyclical factors. The problem with calling it a structural slowdown is that it fails to explain the sudden deceleration in the past year or the boom earlier as it focuses on the long-standing structure of the economy, they wrote. Cyclical factors alone also don't explain the sudden fall in demand as key components of demand have weakened for nearly a decade, the paper said.

The balance sheet problems leave limited room for transmission of repo rate cuts, and administering banks to lower rates will not provide banks with enough risk cover, according to Subramanian and Felman.

Fiscal policy cannot be used because the financial system would have difficulty absorbing the large bond issues that stimulus would entail, they wrote. Moreover, they said, the traditional structural reform agenda—land and labour market measures—will not address the current problems.

Instead, they said, what will work is launching an asset quality review, making changes to the insolvency code, creating a bad bank, strengthening NBFC regulations, shrinking public sector banks and linking recapitalisation to resolution. They also recommended agricultural reforms including direct transfers, creating a single market for agri-products, ending trade policies based on prevailing domestic prices, adoption of new technology and water conservation.

“A slow-bleed over many years led to the current predicament. The way out will also be laborious. India's weak state capacity and the entrenched stigmatized capitalism has stymied private initiative and honest public officials for a very long time. There are no quick solutions.”

But foremost, according to Subramianian and Felman, there is a need for data reforms. Measurement of several economic indicators have proved problematic and the government needs to reboot data systems in the real, fiscal and financial sectors, the paper said.

Essential Business Intelligence, Continuous LIVE TV, Sharp Market Insights, Practical Personal Finance Advice and Latest Stories — On NDTV Profit.