There is visible frustration among Indian policymakers on the issue of bad loans.

“Once you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, no matter how difficult, must be the solution,” wrote chief economic adviser Arvind Subramanian in the Economic Survey while making the case for a bad bank termed as PARA (Public Sector Asset Rehabilitation Agency).

“I think we have to remain open to all solutions at this point, because I think the problem is quite large,” said Viral Acharya, the newly appointed deputy governor at the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) on Wednesday.

That the problem is large has been clear for some time now.

At the end of the September quarter, gross bad loans were just under Rs 6.5 lakh crore. Not all banks have reported earnings for the December quarter, but that number will likely rise further. In percentage terms, bad loans will probably hit 10 percent of all loans by March 2018, by the RBI's own estimates.

What is not clear is whether a bad bank will succeed where other schemes have failed.

To be sure, while the government is looking into the idea, they are treading carefully. They recognise the pitfalls of the such an idea but they also see that there aren't too many options left, said a person familiar with the discussions.

‘Barking Up The Wrong Tree'

Two senior bankers that BloombergQuint spoke to were not convinced that a bad bank is the way to go. We're barking up the wrong tree, said the first banker while requesting anonymity.

The one question that both bankers asked: where will the capital come from?

While neither the government nor the RBI have gone into the details of how a bad bank would be structured, it is fair to assume that assets would be transferred from the books of a bank to any potential bad bank at a significant discount. To be in a position to do this, banks will need to set aside capital. Since banks are already thinly capitalised and raising funds from the market hasn't been easy, this capital will have to come from the government. Capital will also be needed to fund the bad bank.

What is the point of talking about this when the capital is not available, said the banker quoted above.

Hemindra Hazari, an independent analyst who tracks the banking sector, explained in a conversation with BloombergQuint that when a bank sells an asset to an asset reconstruction company (which is similar to a bad bank) it needs to take a haircut but banks do not have the capital to take a haircut. The second question, said Hazari, is who is going to fund the bad bank?

“If we are depending on the generosity of the government then we have seen the Rs 10,000 crore they have provided this year for entire banking sector. In my view, that is enough to provide for just two corporate accounts,” Hazari said in an attempt to illustrate the struggle for capital faced by the banking sector.

The government, or at least the chief economic adviser, however, doesn't believe that capital is the problem.

“So far, public discussion of the bad loan problem has focused on bank capital, as if the main obstacle to resolving TBS (the twin balancesheet problem) was finding the funds needed by the public sector banks. But securing funding is actually the easiest part, as the cost is small relative to the resources the government commands. Far more problematic is finding a way to resolve the bad debts in the first place,” said the Economic Survey.

Also Read: Economic Survey Pushes For PARA - A Central Bad Bank To Resolve Large Stressed Loans

Will A Bad Bank Be Better At Resolving Stressed Assets?

The second banker quoted above said that resolving the current pile of large stressed accounts will be a problem no matter which agency holds them. This banker explained that banks have been trying to resolve a number of these sticky assets but have run into three key problems: getting a proper turnaround strategy in place; tackling legal obstacles; and finding enough capital to support the turnaround.

The first banker added that there has been no forum of “orderly reorganisation”, while adding that all decisions are subject to questioning which means that bankers are reluctant to take tough calls.

Both bankers agreed that resolving stressed cases under the new Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code is the best option but will take time. It will take 18-24 months before we can see resolution under the Bankruptcy Code and that is too long to wait, said the first banker.

According to them, bankers have suggested alternatives to the government and the RBI but none of the suggestions have been accepted.

In particular, banks have been lobbying for a relaxation in the rules applicable the S4A (Scheme for Sustainable Structuring of Stressed Assets), which would allow more accounts to be restructured under the scheme. At present, the scheme requires that half the debt should be ‘sustainable' and the company should be able to service this debt with existing cash flows. Banks want this condition eased but the RBI has not yielded in the fear that this will lead to ever-greening of inherently unsustainable accounts.

According to two people familiar with the discussions, bankers have also suggested that they be allow to create bad banks within their own individual banks. This is concept that was tried by IDBI Bank Ltd. In 2004, when IDBI Ltd. converted itself to a bank, the government had decided to set up a Stressed Asset Stabilization Fund (SASF) which held the bad loans of IDBI.

The question, then, is whether an external agency (like a bad bank) would have greater success in resolving stressed assets than some of the most seasoned bankers?

“Even if you have a bad bank and transfer these assets at a huge loss to the banking sector, how are you going to recover the money?” asks Hazari.

To be sure, the regulator is mindful of the fact that this is the key question to answer before experimenting with a bad bank.

“The big piece of the problem is can you get the bank to sell the assets at the right price to ARCs (asset reconstruction companies) and private investors who want to come in? How to get that right price by using a portfolio or a bad bank approach is going to be key. We are going to be thinking about what kind of design could help with that,” said RBI deputy governor Acharya on Wednesday.

Also Read: Does India Need A Bad Bank To Clean Up The Bad Loan Mess?

Little Support From The Economy

In making a decision on whether to create a bad bank, policymakers will also do well to take note of the nature of the bad loan problem this time around.

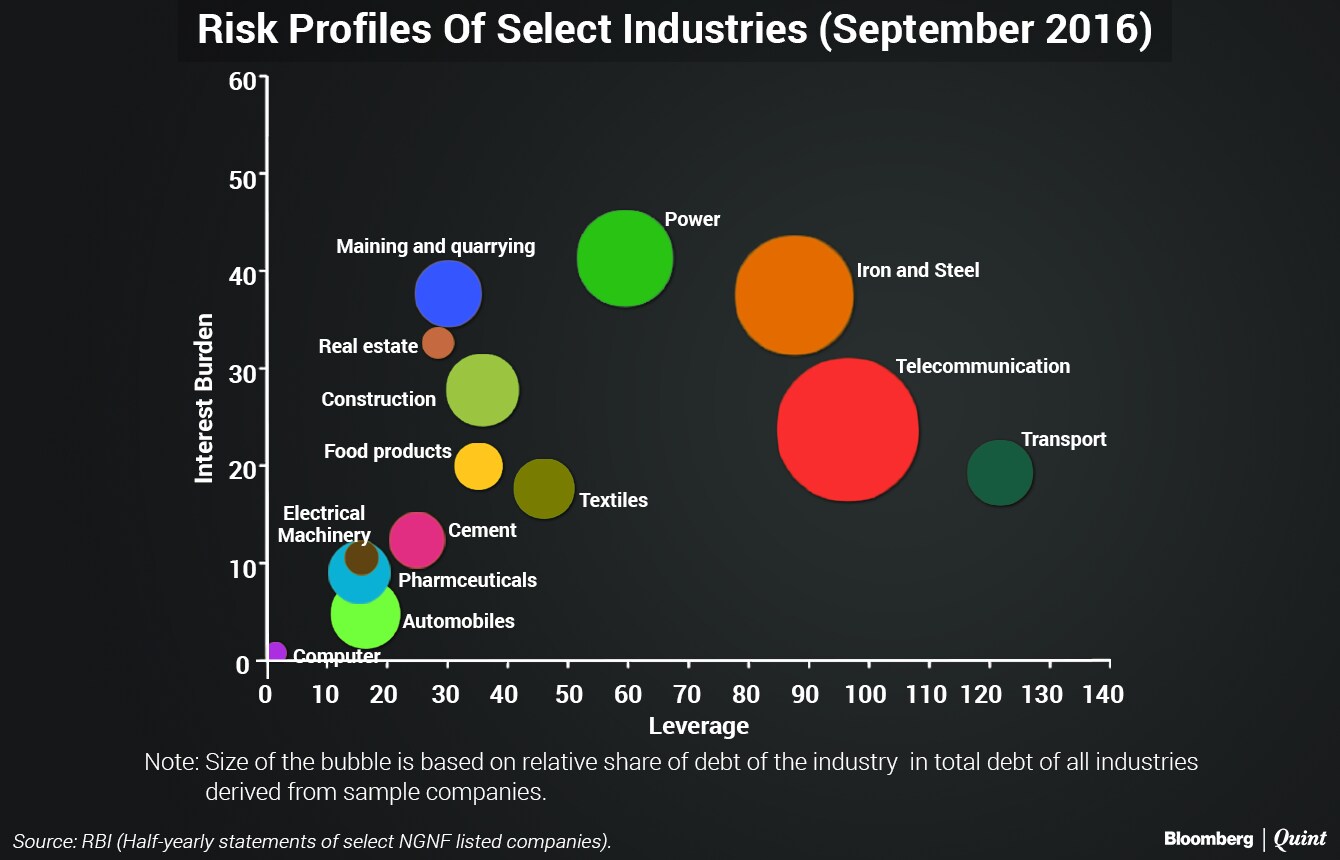

The problem is not only centered in a handful of business groups but also in just a few sectors. As such, the ability to recover loans may depend on the prospects of recovery for these sectors.

As the graphical representation, first published in the RBI's Financial Stability Report, shows, companies in the steel, telecommunications and power sectors account for a large part of the stress.

The prospects for each of these sectors looks bleak. While the rise in global commodity prices has helped the steel sector, demand conditions at home remain subdued due to the lack of private investment in the economy. The power sector is sitting on excess capacity and the telecom sector is in the middle of a price war.

None of this bodes well for a quick recovery of stressed assets.

KC Chakrabarty, former deputy governor of the RBI and career public sector banker, says that the government and the regulator have allowed this problem to drag on for too long, making it unmanageable.

“One thing is clear that this problem cannot be resolved at the bank level anymore. It has become too large,” said Chakrabarty. Some kind of a centralized asset reconstruction agency or a credit resolution agency is needed, he said. Chakrabarty, however, added that many unanswered questions remain including the actual size of bad loan problem and the availability of capital.

“It is likely debating whether to feed people at one location or multiple locations. But you don't know where the food and the money for the food will come from,” he summed up.

Essential Business Intelligence, Continuous LIVE TV, Sharp Market Insights, Practical Personal Finance Advice and Latest Stories — On NDTV Profit.