(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Berkshire Hathaway Inc. reported its stock holdings last week — a widely anticipated quarterly update of Warren Buffett's latest trades. There were some notable ones, including the addition of Domino's Pizza Inc. to Berkshire's portfolio and more trimming of its stake in Apple Inc.

But those moves have been overshadowed by Berkshire's $325 billion cash hoard, nearly double the company's cash balance at year end, and the most Buffett has ever amassed. It also comes at a time when Buffett's favorite valuation gauge — a ratio of the stock market's value relative to the size of the US economy – is at a record high.

Taken together, it might seem as if Buffett is trying to time the market's next downturn, but what he's doing is more subtle and thoughtful — and instructive for investors.

Buffett is the first to acknowledge that he has no ability to predict where the market is headed in the near term, including the timing of its occasional meltdowns. What he can do, however, is estimate how much stocks are likely to pay over the longer term and use that estimate to decide how much to allocate to stocks relative to other assets.

It's an important distinction. There's a difference between betting on turns in the market, which is extremely difficult if not impossible to do profitably, and deciding how to allocate to various assets based on their expected longer-term returns, which can be reliably although not perfectly estimated. In other words, it's the difference between betting on the market's unknowable path versus its likely destination.

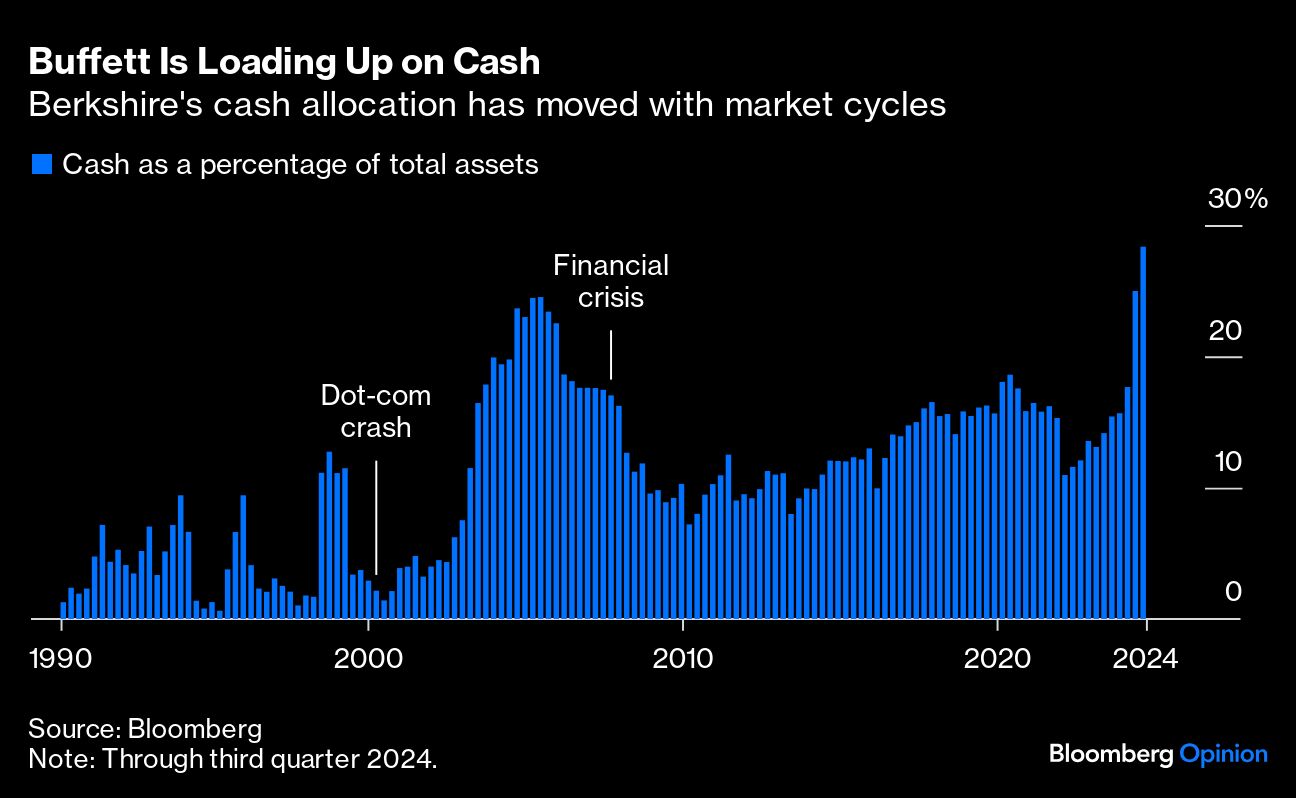

That principle appears to have long guided Buffett's decisions. Berkshire's allocation to cash as a percentage of the company's assets has varied considerably over the years, from 1% in 1994 to closer to 28% today, and everything in between. The record shows Buffett consistently raising Berkshire's cash allocation as stock valuations rise during booms — and expected returns consequently decline — and drawing down cash as opportunities arise. It also confirms that Buffett has little talent for market timing, as he readily admits.

For instance, during the internet bubble in the late 1990s, Buffett grew his cash allocation to 13% of assets in 1998 from just 1% four years earlier as valuations swelled. But he drew down his cash allocation to 3% in 1999, about a year before the bubble burst, presumably because he found an attractive target. In retrospect, he probably would have been better off sitting on that cash for another year when bargains became plentiful, but not even the great Buffett can see the turns coming. He did the next best thing, though, which is employ almost all of Berkshire's cash through the downturn.

Then he pivoted again in the run-up to the 2008 financial crisis. Buffett began raising his cash allocation substantially when the market recovered in 2002, eventually topping out at 25% of assets in 2005. Berkshire's cash allocation started to dip in 2006, mostly because the value of its assets continued to rise. But when a whiff of the coming crisis sent stock prices tumbling beginning in late 2007, Buffett deployed his cash and eventually drew it down to 7% of assets in 2010, in part on account of his famously shrewd investment in Goldman Sachs Group Inc. at the height of the crisis.

How does Buffett do it? He's betting on a simple principle, which is that valuations and future returns are inversely related. That is, when assets are expensive, future returns tend to be lower, and vice versa.

It doesn't even matter which valuation measure you use because they generally say the same thing. Buffett's preferred gauge of the stock market — its value relative to gross domestic product — surged in the late 1990s and again in the mid-2000s, signaling lower stock returns ahead. Both times, cash yields were around 5%, and expected stock returns weren't much higher, if at all. Given those choices, it made sense to have some cash around.

Today, the market-to-GDP ratio is even higher than it was in the late 1990s and mid-2000s, implying even lower future returns. Meanwhile, cash pays about the same as it did then. No wonder Berkshire's cash allocation is the highest since at least the mid-1980s.

Buffett is far from alone. In fact, I can't recall a time when there's been so much agreement that US stocks are poised to disappoint, at least by historical standards. The biggest money managers, including BlackRock Inc., The Vanguard Group, Goldman Sachs and JPMorgan Asset Management all expect the US stock market to fall well short of its historical return of 9% a year over the past 150 years.

It's hard to argue with that consensus. Stock investors essentially get paid three ways. One is shareholder yield, which is a combination of dividends and buybacks. A second is earnings growth resulting from higher sales or expanding profit margins. And the third is change in valuation.

Here's how things look: The S&P 500 Index's dividend yield is 1.3%, and its most recent 12-month buyback yield was 1.8%. As for earnings, analysts expect sales to grow by about 4% a year over the next several years, which is in line with historical sales growth. They also expect record high profit margins to stay where they are rather than contract — a generous assumption, but let's go with it. And as for valuation, the S&P 500 trades at 25 times forward earnings, compared with an average of 18 times since 1990. To get back to average, its valuation would have to contract by about 3% a year for 10 years, if a sharper contraction like the one in 2022 doesn't come along sooner.

All of that adds up to an expected return of about 4% a year for the S&P 500 over the next decade, which, probably not coincidentally, is roughly in line with the average expected return calculated by the big money mavens. It's also not terribly exciting when compared with the 4.4% yield on risk-free three-month Treasury bills.

No one can reliably anticipate the market's path, which is why you'll never see Buffett make all-in, all-out moves around the market. But the destination is easier to estimate, particularly when the market is glaringly expensive. And when that destination promises so little relative to cash, watch Buffett beef up his rainy-day allocation.

More From Bloomberg Opinion:

No, China Doesn't Really Have a Debt Crisis: Shuli Ren

AI's Slowdown Is Everyone Else's Opportunity: Parmy Olson

Trump Tariffs Will Crash Into Inflation Fatigue: Jonathan Levin

Essential Business Intelligence, Continuous LIVE TV, Sharp Market Insights, Practical Personal Finance Advice and Latest Stories — On NDTV Profit.