The Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) begins its final two-day meet of the current fiscal year today. The post budget monetary policy is typically dominated by discussion on whether the government's policies will have a bearing on the path of growth and inflation in the economy, and if fiscal consolidation efforts have kept pace with expectations. This time will be no different. However, unlike the last couple of years, this time, the government may have given the MPC cause to worry. Three causes to be precise.

Fiscal Targets & Inflation Targets

The first issue for the MPC to ponder is whether the government's decision to cut itself some fiscal slack will impact the MPC's ability to meet its inflation target in a durable fashion. Before getting to the current inflation scenario, it may be worth revisting the Urjit Patel Committee report of 2014, which laid the groundwork for the flexible inflation targeting framework that India now operates in.

While addressing the institutional requirements for an inflation targeting regime, the Patel committee had said that the adoption of such a framework should be based on reasonably clear pre-conditions. Among these was a commitment to fiscal consolidation. The committee, in fact, was specific about what it thought was required to support an inflation target of 4 (+/- 2 percent).

“The Committee is of the view that the goal of reducing the central government deficit to 3 percent of GDP by 2016-17 is necessary and achievable. Towards this objective, the Government must set a path of fiscal consolidation with zero or few escape clauses; ideally this should be legislated and publicly communicated,” said the Patel committee report.

Patel, now the governor of the Reserve Bank of India, is unlikely to ignore the fact that the 3 percent fiscal deficit target has been pushed back to FY21. The medium term fiscal framework put out together with the budget, shows that the government will target a 3.3 percent deficit in FY19, 3.1 percent in FY20 and 3 percent in FY21. To calm frayed bond market nerves, Subhash Garg, secretary of the Department of Economic Affairs, said that the 3 percent target may be achieved sooner than expected in FY20. That twitter pronouncement, however, may not sway the MPC.

Also Read: Union Budget 2018: Government Gives Itself A Fiscal Long Rope

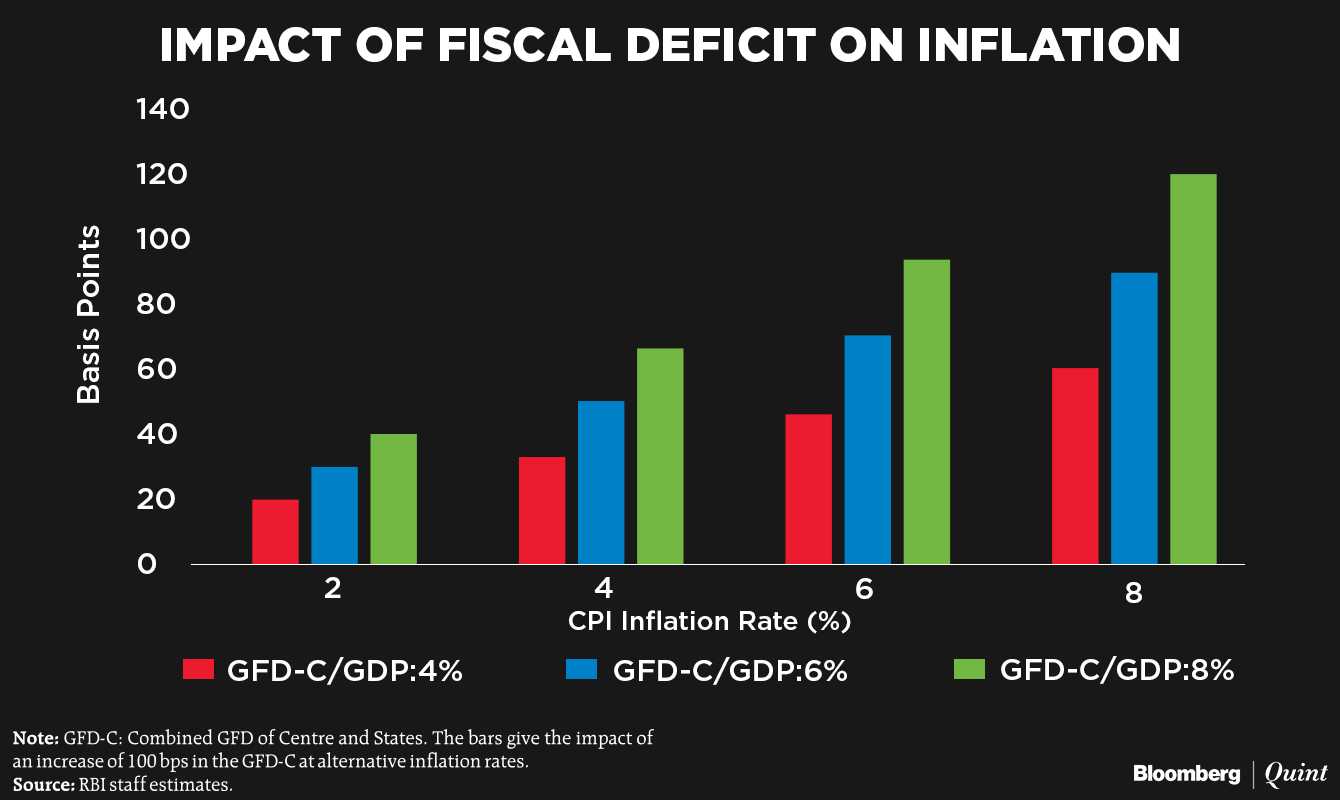

Apart from the Patel committee report, more recently, the RBI put out estimates on the impact of a wider fiscal deficit on inflation. In an analysis included in the October 2017 Monetary Policy Report, RBI staffers highlighted three factors:

- There exists a long-run relationship between fiscal deficits and inflation in India

- Causality runs from fiscal deficits to inflation

- The impact of fiscal deficits is higher when the initial levels of inflation and fiscal deficit are higher

“With the combined fiscal deficit budgeted at 5.9 percent for 2017-18, empirical estimates suggest that an increase in the fiscal deficit to GDP ratio by 100 bps could lead to a permanent increase of about 50 bps in inflation,” said the report.

Should the MPC be willing to forgive the government a fiscal slippage in light of structural changes like GST and take note of the expenditure control attempted next year? Or should it adopt a tougher stance and sound more hawkish? That's one dilemma for the committee to resolve.

Support Prices & Food Inflation

The second issue for the MPC to debate is food prices. The spillover of higher food prices into inflation expectations and then generalized inflation in India is now widely recognized. The question is whether the government's changed stance on minimum support prices will set off that cycle. In the budget, the government said that it would ensure 1.5 times cost of production during the Kharif reason. This is similar to the promise made for the Rabi season.

Will this lead to higher inflation? There are different views on this.

Bank of America-Merrill Lynch argues that the inflationary impact of the MSP policy will be limited. According to them, the revised MSPs are still below market prices in many cases. Since the consumer price index already captures market prices, which are higher, the MSP changes may not have much impact.

Nomura said that the inflationary impact will depend on the extent of MSP hikes as every 1 percent rise in MSP adds 10-15 basis points to headline CPI inflation. “We doubt the actual MSP rise will be as high as the headline (cost +50 percent) suggests, but this is an upside risk to inflation,” said the brokerage in a report after the budget was announced.

According to Sajjid Chinoy of JPMorgan, the inflationary impact may flow from paddy where the prevailing MSP is 38 percent above cost. If that has to go to 50 percent above cost immediately, then the impact would be 70 basis points to headline inflation, said Chinoy. He, however, said it is not clear over what time period MSPs would be raised and what estimates of cost of production would be used. The Commission of Agricultural Costs and Prices uses two different methods to ascertain costs.

The MPC will need to measure all these scenarios and see whether it wants to communicate heightened upside risks to inflation.

Borrowings & Rates

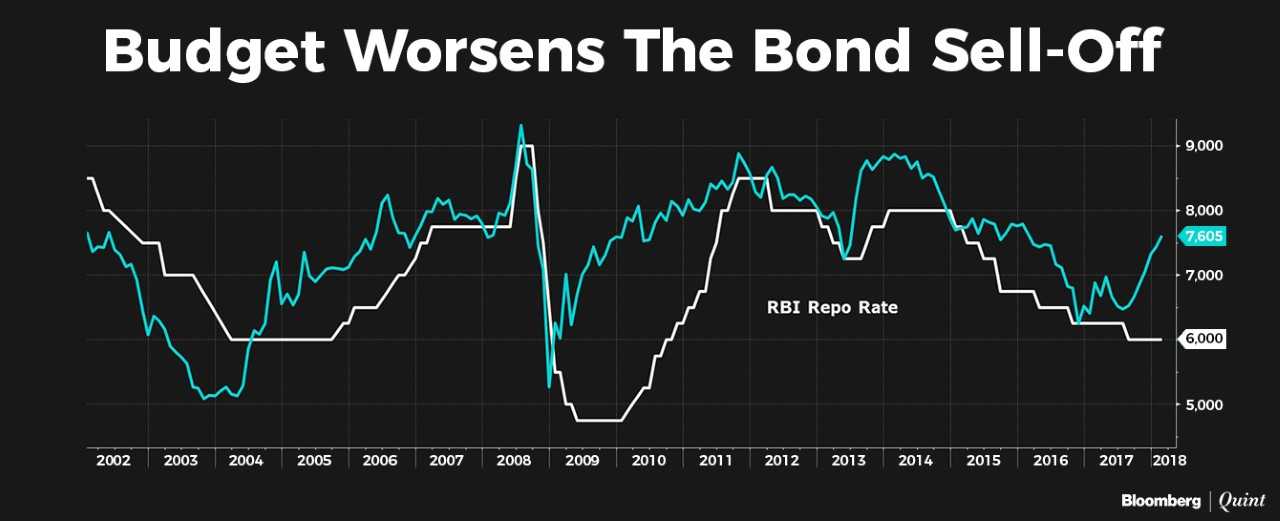

The nervousness in the bond markets and the surge in bond yields over the last few months may also need to be taken into account by the MPC.

As Neelkanth Mishra of Credit Suisse told BloombergQuint in a recent conversation, a much larger proportion of borrowings are now exposed to movements in the money market. This is because incremental borrowings have moved towards bond markets over the last couple of years where rates were lower than those offered by banks. Bond market rates should now be seen as the policy benchmark rather than the repo rate, argued Mishra noting that the yield increase over the last six months would be equivalent to three quarter percentage point rate hikes. At current levels, the 10-year benchmark bond yield is nearly 150 basis points over the RBI's repo rate.

Also Read: Was The Budget Trying To Fix India's Two-Speed Economy?

The RBI staffers on the MPC may not see it exactly that way. At the press conference following the December monetary policy review, governor Patel had dismissed talk of tight liquidity conditions and pointed to the range-bound overnight money market (call money) rate. That rate remains at near 6 percent - in line with the repo rate.

Still, the MPC will probably not ignore the impact of large government borrowings on market interest rates. For FY19, the government has announced gross borrowings of Rs 6 lakh crore. The markets are skeptical. Morgan Stanley in a note said that the actual number will be closer to Rs 6.4 lakh crore. In a year when credit demand is picking up, deposit growth has normalised and foreign investment limits are close to being exhausted, large borrowings will mean higher interest rates for corporates. A number of economists have suggested that this could hamper an early economic recovery.

If the RBI (liquidity management is more the RBI's preserve than the MPC's) takes that view, it may signal its willingness to maintain a looser liquidity stance. But can it afford to do so if inflation risks are rising? Yet another tough judgement call that needs to be made.

Essential Business Intelligence, Continuous LIVE TV, Sharp Market Insights, Practical Personal Finance Advice and Latest Stories — On NDTV Profit.