India's digital payment systems have gained much acclaim, and deservedly so. The volume, value and variety of digital payments systems have all grown dizzyingly over the last decade.

Yet, cash is far from beat and, in fact, still plays a valuable role particularly in the informal sector and in the rural economy.

A non-trivial amount of cash infusion in the rural economy originates from the government's direct benefit transfers and domestic remittances. But only a third of bank branches are rural, and ATMs often run dry even when present. As per RBI's last annual report, this cash gap is being serviced by nearly 18 lakh business correspondent agents or BCAs, a large proportion of them contracted by private sector banks.

BCAs use the Aadhaar Enabled Payments System, or AePS, on so-called micro-ATMs, online devices connected to banking systems, to allow customers to withdraw cash, simply using their Aadhaar number linked to their bank account and a fingerprint as authorization.

But the economics of the crucial mechanism of making cash available in remote rural locations are unfavourable to those who are servicing it – the public sector banks.

A sense of scale may be important in understanding the issue.

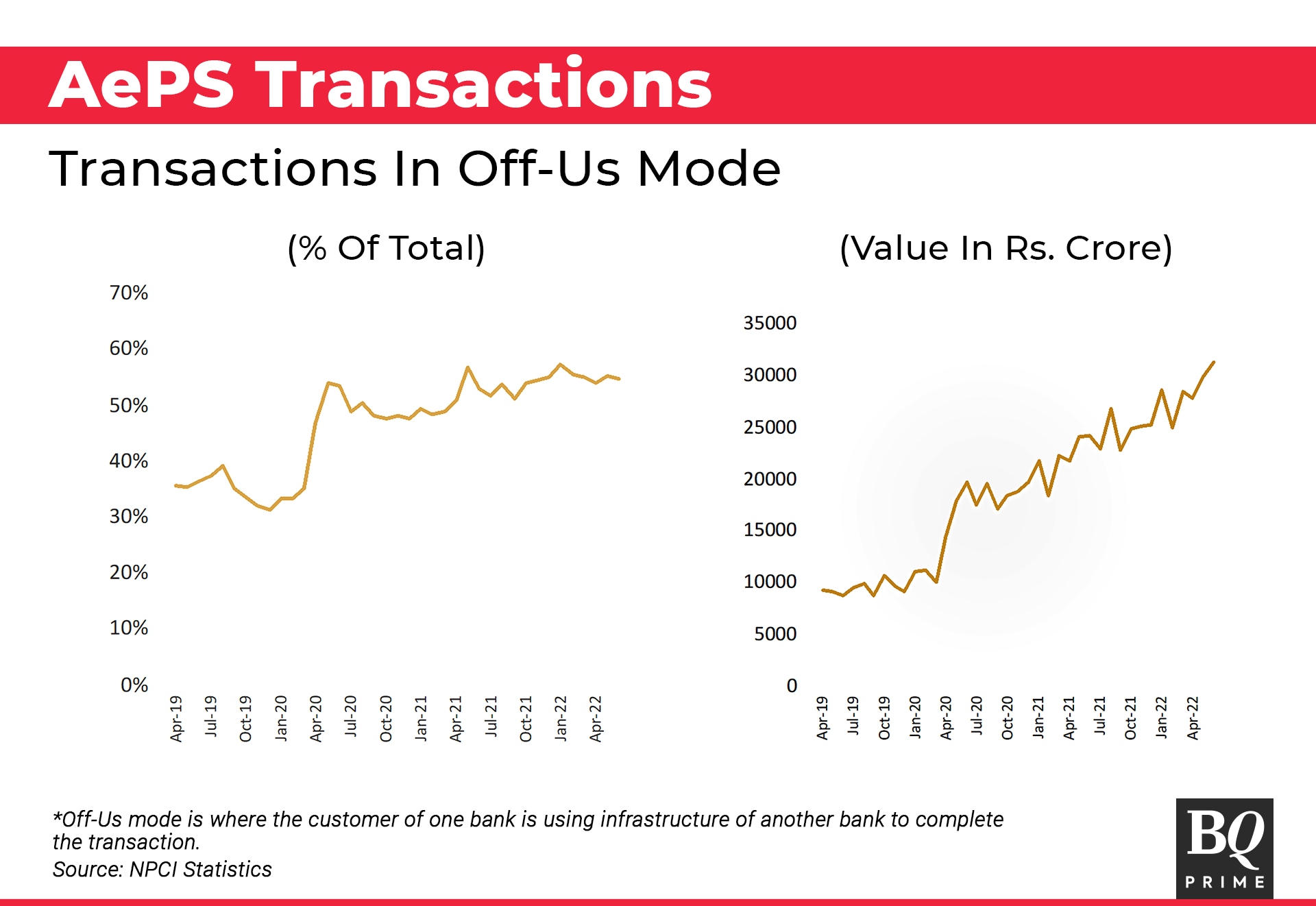

In June 2022, AePS run by the NPCI clocked 45 crore transactions worth Rs 31,373 crore, averaging Rs 700 per transaction. Most cash withdrawals on AePS are of funds received digitally by rural Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana account holders from direct benefit transfer\welfare payments or domestic migrant remittances.

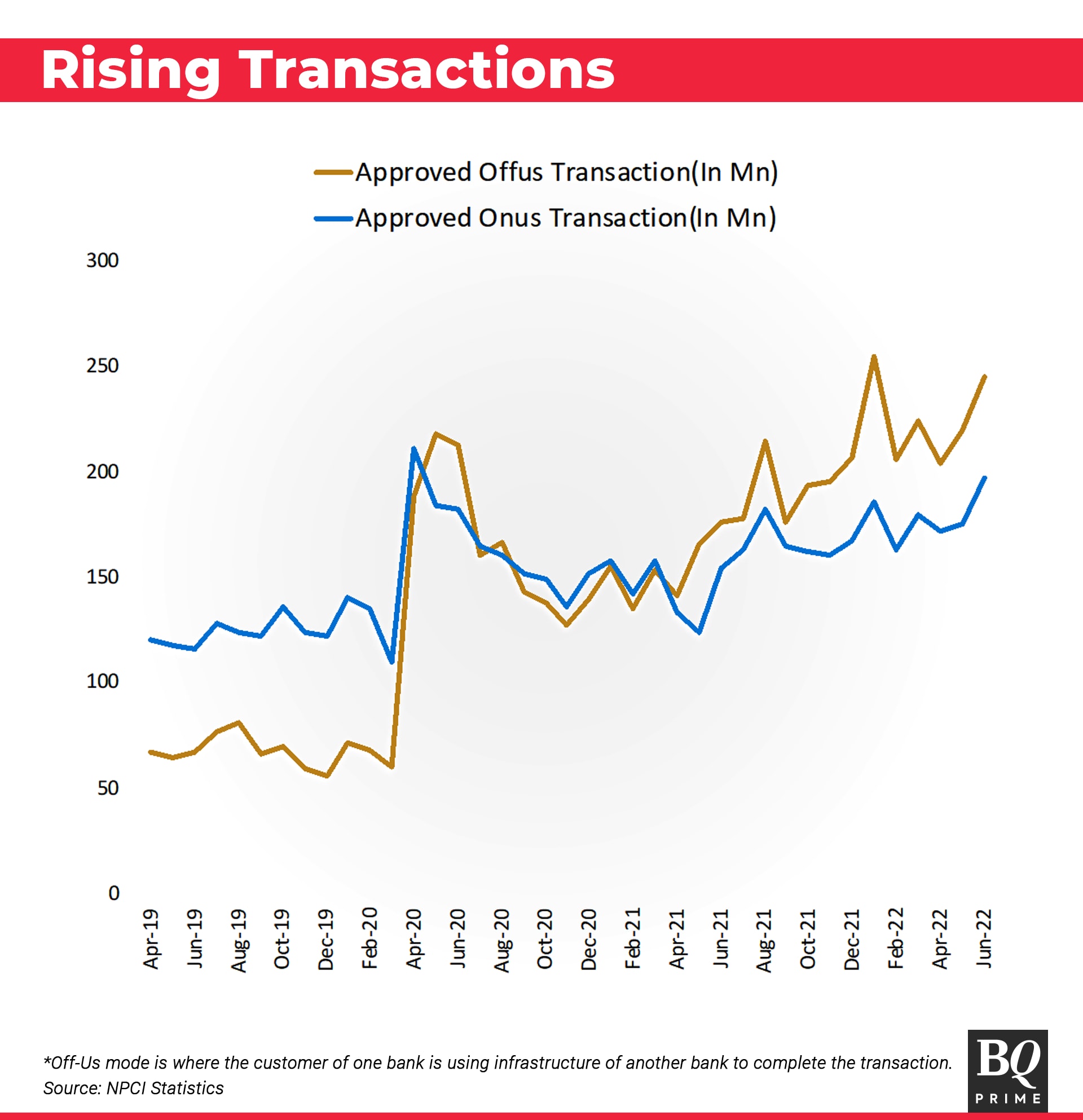

A majority of AePS transactions are ‘off-us' transactions, which means that a customer of one bank is using the infrastructure of another bank to complete it.

AePS Economics vs ATM Economics

In many ways, the AePS system has been built along the lines of the ATM system.

NPCI enables full interoperability for AePS transactions. This means customers of one bank can withdraw cash from agents of another bank if their account is linked to their Aadhaar number. This is based on the ATM interoperability model that was the progenitor of the NPCI, whose interoperability scheme enables customers of any bank to use their debit card at an ATM of any other scheme participant bank, to make cash withdrawals.

In the case of ATMs, which are concentrated in urban areas (75% per RBI data), used by more affluent users, the ‘acquiring bank', which installs the ATM, refills it with cash, pays rent and electricity, provides security, and operates it, is paid an ‘interchange fee” by the “issuing bank” (one that issued the account and debit card) for providing cash withdrawal services to its customers. This is fair since the cost of the ATM itself is upwards of Rs 4 lakh and running one involves significant operating expense.

Recognising this cost, the interchange fee was increased from Rs 12 to Rs 15 not long ago. It is widely acknowledged that cash management cost ranges from 0.6-1% varying from urban-rural as a measure of remoteness.

The AePS system, on the other hand, involves a handheld device linked to a biometric reader that costs about Rs 4,000, paid for and owned by the BCA.

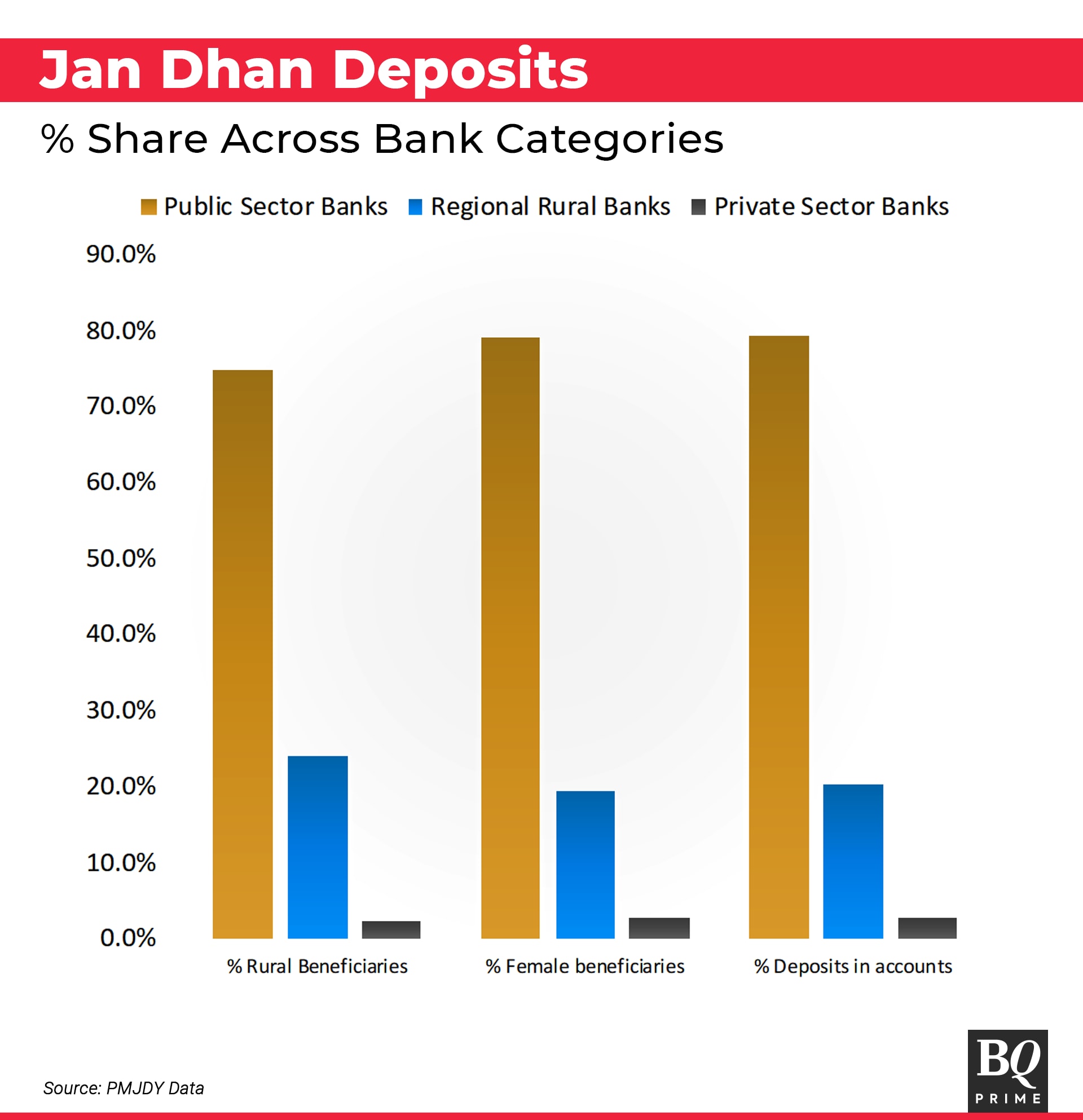

Rural BCAs provide cash withdrawal services overwhelmingly (9 in 10 transactions) to customers of public sector banks or regional rural banks – as is evident from the distribution of PMJDY accounts in the chart below.

However, a material share of BCAs are attached to private banks. While there is a fair population of rural BCAs of PSU and RRBs too, they tend to operate laptops or slightly more expensive customised handheld devices. As such, a bulk of the AePS transactions are being facilitated by private sector BCAs.

Therein lies the concern.

Private banks get an interchange fee from PSUs each time their customer approaches a BCA of the former.

As a broad approximation, at 55% of 45 crore or 24.75 crore transactions, assuming an average interchange of Rs 7 per transaction, PSUs will pay around Rs 173 crore per month or Rs 2,080 crore in FY22-23 (up from about Rs 1,638 crore in FY21-22) in interchange fees to private banks to service cash withdrawals to their own customers.

This cost appears unjustified if PSUs continue to bear the bulk cash management cost.

Unlike operating ATMs, which needs licences, much bigger capital investment, higher operating expenses, and institutional and reputational barriers, the AePS BCA system only requires a hand-held device operated by trained personnel. The capital investment is about 1% compared to an ATM and the operational expense is significantly lower. Hence it could be argued that the interchange fee required to use this network does not need to comparable to the case of the ATM network.

What's The Solution?

There are solutions to address this issue of interchange bleed for PSUs, without destroying interoperability and inconveniencing customers.

The first is to evolve a ‘BCA cash supply interchange'. This would mean that the any BCA is allowed access to bulk cash from another bank (not its principal) at an agreed percentage of the value drawn. Hypothetically, at 0.3% this would mean that the private bank or their BCA pays the PSU Rs 300 on every Rs 1 lakh drawn. This would likely level the playing field since the PSU continues to earn from cash supply, while private bank BCAs continue to earn from serving clients conveniently.

The second is to reduce the interchange fee for AePS transactions, acknowledging the value of PSU cash supply to private bank BCAs.

The third is for PSUs to increase their own network of BCAs to reduce off-us transactions for which they incur interchange fees.

And the fourth is for private banks to step up and increase rural branch presence, ensuring cash supply to their own BCAs.

A combination of these can help sustain cash withdrawals by BCAs and prevent denial of service to excluded rural poor, women, mobility restricted, and elderly customers.

Updated on Aug. 6, 2022, to correct a statement on the provision for free cash withdrawals that apply to ATMs and do not extend to AePS.

Anand Raman is an independent consultant in inclusive finance and digital payments. He has 29 years of experience across information technology, telecommunications, media, and financial services.

The views expressed here are those of the author's and do not necessarily represent the views of BQ Prime or its editorial team.

Essential Business Intelligence, Continuous LIVE TV, Sharp Market Insights, Practical Personal Finance Advice and Latest Stories — On NDTV Profit.