Tata Vs Mistry And Other Family Feuds: The Promise And Peril Of Family Group Companies

I teach a corporate finance class, a class that I describe as big picture (since it covers every aspect of business), applied and universal in its focus. I use six firms, ranging from large to small, developed (Disney and Deutsche Bank) to emerging (Vale and Baidu) and public to private (a privately-owned bookstore in New York), as lab experiments to illustrate both corporate finance first principles and financial models or theory.

One of my illustrative companies is Tata Motors to illustrate the special challenges associated with managing and investing family group companies, where the conflict between what’s good for the family group and for the company can play out in every aspect of corporate finance. I picked a Tata group company for a simple reason – among Indian family groups, it is among the most highly regarded, and my intent was to show that even in the best run family group companies the potential for conflict lies just under the surface and events over the last few weeks has added weight to that argument.

The Tata Group, The Enlightened Family Group?

It is not hyperbole to say that the Tata family and Indian business have been intertwined for much of the last two centuries. The first Tata company came into being in 1868 and it was built up incrementally and often through difficult times to become the behemoth that it is today. Along the way, it spread itself across many businesses, creating what would have been a classic conglomerate, if it had stayed as one company. In typical family group style, though, it chose to pursue each business with a separate entity and by 2016, the group included more than 100 companies, with 29 of these being publicly traded, standalone entities.

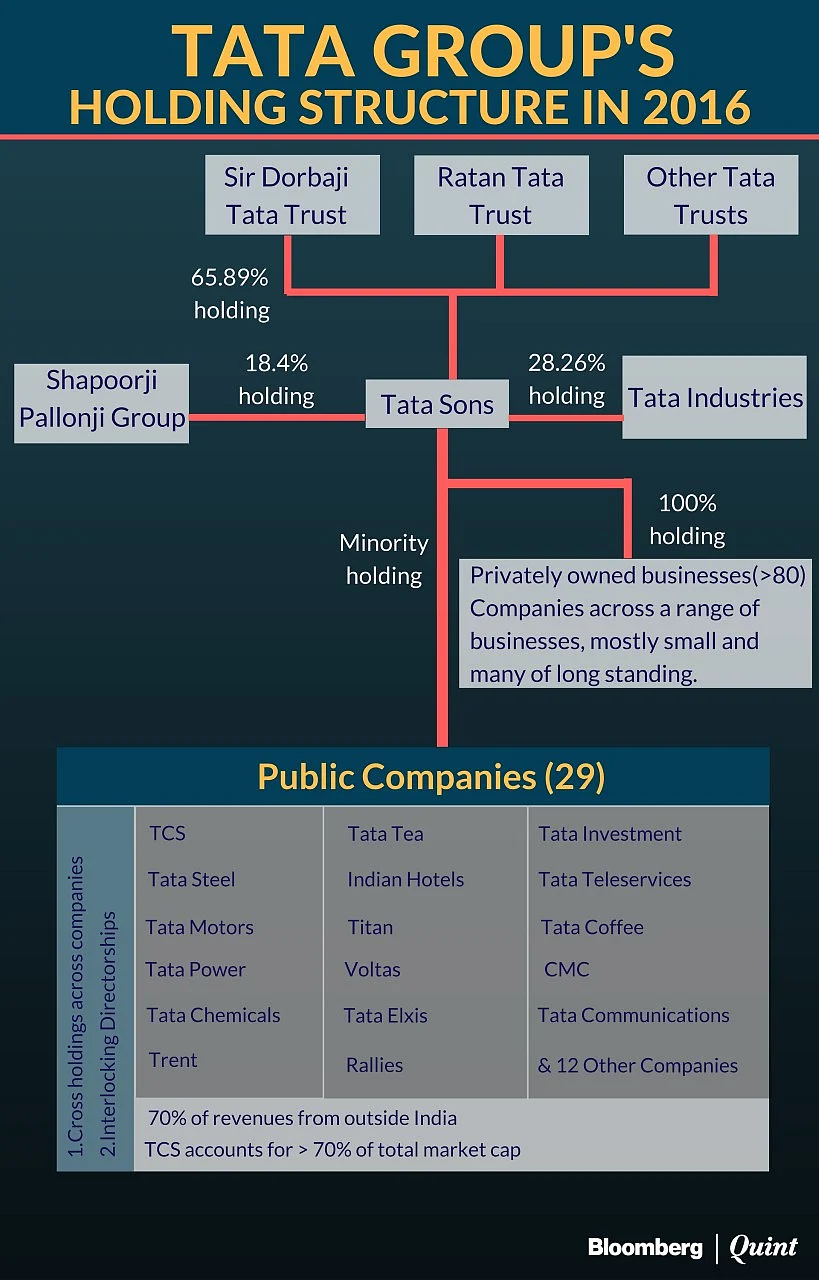

The picture below captures the company's holdings and control structure in 2016.

Note how the companies are all bound together by Tata Sons, which, in turn, is controlled by the Tata Trusts, holding close to 66 percent, with power lying with the Tata family. As a side note, the largest non-Tata stockholder is the Shapoorji Pallonji Group, which controls 18.4 percent of Tata Sons. While each publicly-traded company in the group is an independent entity, with a CEO and a board of directors (with a fiduciary responsibility to protect the shareholders of that company), the independence is illusory. Not only does Tata Sons own a significant piece of each company, the companies all own shares in each other (cross holdings effectively controlled by the family group) and directors representing family group interests serve on each board.

Note that though much is made of the conglomerate nature of the Tata Group, the group derives the bulk of its value (more than 70 percent) from TCS, a technology company that derives most of its revenues from outside India.

It is a testimonial to the stability and continuity in the Tata Group that it has had only six men at its helm over its 150-year history.

JRD Tata who presided over the company for a large portion of the last century was legendary, not just for his business acumen but his social consciousness and was viewed as India’s most upstanding corporate citizen. In fact, Cyrus Mistry who became chairman of Tata Sons in 2012, was more insider than outsider, backed by Shapoorji Pallonji Group, as a scion of the family (behind that group) and also related by marriage to the Tata family.

This history of stability is perhaps why investors and onlookers were shocked by the events of the last few weeks. On October 24, 2016, the board of directors of Tata Sons fired Cyrus Mistry as the chairman of Tata Sons for non-performance, a failure to deliver on promises. Mistry did not go quietly into the night and fought back, arguing that not only was the removal not in keeping with Tata traditions of decorum and fairness, but that his removal was effectively a coup by old-time Tata hands who were threatened by his attempt to clean up mistakes made by the prior regime (headed by Ratan Tata). In particular, he argued that many of the high-profile acquisitions/investments that Ratan Tata had made, including those of Corus Steel (by Tata Steel) and forays into the airline business (Vistara and AirAsia) were weighing the company down and that it was his attempts to extract Tata companies from these messes that had provoked the backlash. Defenders of the removal argued that Mistry had been removed for just cause and that his numbers-driven (and presumably short-term) decisions were not in keeping with the Tata culture of building businesses for the long term.

The opacity that surrounds the Tata companies with their incestuous corporate governance structures (with directors sitting on multiple Tata companies) and complex holding structures makes it difficult to decipher the truth, but the two sides seem to be in surprising agreement on one point, that the bulk of the value of the Tata Group derives from two investments, TCS and Jaguar Land Rover. In fact, the area of disagreement is about why the rest of the group was in in trouble and what should have been done about them. The Mistry camp argues that the troubles at the rest of the group can be traced back to ill-advised and expensive acquisitions (Corus, Tetley) and investments (Nano) made during the Tata tenure and the Tata camp suggests that Mistry knew about those problems when he was hired and that he did little to fix them during the four years of his tenure. Whatever the truth, the company has a mess on its hands. While Mistry has been forced out at Tata Sons, he remains on the boards of the other publicly-traded Tata companies and was chairman of the board at TCS until a while ago. That sets the stage for a war of attrition, which cannot be good news for any Tata company stockholder or for either side in this dispute, since they both have substantial stakes in the group.

The more general question raised by this episode is a troubling one. If a corporate governance dispute of this magnitude can occur at a family group that many (at least on the outside) viewed as one of the least conflicted in India, and you and I, as stockholders in Tata companies, can do nothing but watch helplessly from the outside, what shred of hope can we have of being protected at other family groups that are much more open about putting their interests over that of stockholders? I remember being asked after I had completed a valuation of Tata Motors a few years ago whether I would buy its stock and shocking my audience by saying that I would never buy a Tata company for my portfolio. When pushed for my rationale, I said that buying a family group company is like getting married and having your entire set of in-laws move into the bedroom with you; in investment terms, if I invest in Tata Motors, I will (unwillingly) also be investing in many other Tata Group companies, because about 30-40 percent of the value of Tata Motors comes from its holdings in other Tata companies.

The 4Cs Of Family Businesses: The Trade-Off

As an investor, I may not be inclined to invest in a family group company but it is undeniable that in much of Asia and Latin America, family group companies not only dominate the business landscape but have played a key role in economic development in the countries in which they operate. Consequently, there must be advantages they bring to the game that explain their growth and continued existence and here are a few:

Connections: In many countries, including populous ones like India, influence is wielded and decisions are made by a surprisingly small group of people who know each other not just through their business networks but also through their social and family connections. These “people of influence” include bankers, rule makers and regulators that determine which businesses get capital, what rules get written (and who gets the exceptions) and the regulations that govern them. Family group companies have historically used these connections as a competitive advantage against upstart competition (both from within and without the country), especially in an environment where you have to pass through a legal, bureaucratic and political thicket to start and run a business.

Capital: Extended family group companies create internal capital markets, where profitable and mature companies in the group can invest their excess cash in growth companies within the same group that need the capital to grow. This works to their advantage, especially when external capital markets (stock and bond) are illiquid and poorly developed and in countries that are susceptible to shocks (political or economic) that can cause markets to shut down.

Control (Good): I have always taken issue with analysts who blithely add control premiums to the estimated values of target companies in acquisitions, not because I don’t think control has value but because I believe that to value control, you have to be specific about what you would change in the acquired company. Control is absolute in family group companies, sometimes because the families own controlling stakes in each of the companies in the group and sometimes because they have skewed the rules of the game in their favour (through opaque holding structures and shares with disproportional voting rights). In the benign version of this story, family groups use this control to make decisions that are good for the long term value of the company but that may be viewed negatively by “short-term” investors in markets. Not having to pay attention to what equity research analysts write about their companies or look over their shoulders for hostile acquirers and activist investors may give family group companies advantages over their competitors who may be more vulnerable to these pressures.

Culture (Good): A successful business is usually driven not just by quantitative objectives but also by a corporate culture that is unique and binds those who work at that business. In a non-family group company, that culture may come from the ethos of the top management of the company but is more susceptible to change than at a family-group company, where the family culture not only is much more pervasive but more long term. To the extent that the culture that is embedded is a good one, that can be a benefit to the company both in terms of retaining employees and customer trust.

The research on family group companies is still in its nascency but the studies that I have seen seem to find strengths in these businesses, relative to conventional companies. That said, each of these advantages can very quickly be flipped to become disadvantages and here is that list:

Connections -> Cronyism: I have no moral objections to building connections-based businesses, but if your primary competitive advantage becomes the connections that you possess, it is possible that you will rest on that advantage and not work on developing other core competencies. That will put you at a disadvantage when you go into foreign markets, where you don't have the connections advantage or when global competitors enter domestic markets. It is also true that as the connections shift from family and social ones to the political arena you are on more dangerous ground, since a change of regime (democratic or otherwise) can be devastating to your business interests.

Internal Capital -> Cross-subsidisation and Cross-holdings: While there are advantages to letting the cash surplus companies in a family group fund those with cash deficits (and growth potential), there are two potential costs. The first is that without the discipline of an external lender or equity market, investments in companies may not meet bare minimum corporate finance criteria, with intra-company loans made at below-market rates and intra-company equity investments generating returns on capital that are less than the cost of capital. That cross subsidisation not only transfers wealth from your best companies to your worst but can collectively make the group worse off. The other is that these investments and how they are recorded in accounting statements make them more complex and difficult for investors to understand. Valuing a company with twenty cross holdings effectively requires you to value twenty one companies.

Control (Good) -> Control (Bad): If the complete control that families have over family groups gives them the capacity to make long-term decisions that are good for the company, in the face of market disapproval, that same complete control can also lock in the status quo, with inertia determining much of how it makes investment, financing and dividend decisions. Put differently, if a family is mismanaging a business, it can be very difficult to get it to change its ways.

Culture (Good) -> Culture (Bad): The culture of the family can pervade the family group, but that culture can sometimes become an excuse for not acting or even acting badly for two reasons. First, a family culture can go from benign to malignant, more Gambino than Von Trapp, and having that culture pervade an organisation can be deadly. Second, the implicit assumption that family members share a common culture may be an artifact of times gone by, as families splinter and go their own ways. In fact, it is not uncommon to see two siblings or even a parent and a child with very different perspectives on corporate culture battle for the future of a family group.

As you weigh the pluses and minuses of family groups, you can see why they developed as the dominant business form in Asia and Latin America over the last century. Many of the countries where family groups dominate have historically had rule and licence-driven economies with under developed capital markets (illiquid stock markets and state-controlled bankers). Protected in their domestic markets, family group companies have not only been able to grow but keep upstart competitors constrained. As these markets are exposed to globalisation, though, and capital markets open up in these countries, the family group's advantages are declining but they are still entrenched in many businesses.

Back To The Tata Group

If forced to invest in a family group company, I would take a Tata company over many other family group companies. The problem that I see in this latest tussle is less one of venality and more of a failure to adjust to the times and a clash of egos. Ratan Tata's global ambitions, manifested in a spate of acquisitions during his tenure, put the group into businesses and markets where their historical advantages no longer provide an edge.

It is ironic that the two most successful pieces of the Tata group are Tata Consultancy Services, the company that is at odds with much of the rest of the Tata group in terms of focus and characteristics, and Jaguar Land Rover, a global luxury auto maker with a brand name that has little to do with the Tata family.

I am sure that there is no shortage of advice being offered to the group at this time, but these would be my suggestions on what the group needs to do now.

Settle (soon): The dispute between Cyrus Mistry and Ratan Tata has to be settled and soon. Nothing good can come from continuing to fight this out in public and both sides have too much to lose.

This is personal: It seems to me that the fight has become a personal one, with managers and directors taking sides (voluntarily or otherwise) between Ratan Tata and Cyrus Mistry. That tells me that any rational solution will be tough to reach, unless both personalities withdraw from the fray. It seems to me that, for this crisis to abate, Ratan Tata has to step down as chairman and let a third party that both sides find acceptable step in, at least for the interim

Separate the public companies from the private: If this episode shows the danger of tying together all of the Tata companies to Tata Sons and the family group, the first step in untangling them is to separate the 29 public companies from the private companies in the group. The dangers of self dealing and conflicts of interest are greatest when the private businesses interact with the public companies.

Unit independence: The next step in this process is to make each public company truly independent and that will require (a) selling cross holdings in other Tata companies and (b) removing family group directors who serve on the boards of the stand alone companies.

Restrict intra-group activities: It would be impractical and perhaps even imprudent to bar Tata companies from interacting with each other, but those interactions should follow first principles in finance. Hence, while intra-group loans may sometimes make sense, the interest rates on these loans should reflect the risk of the borrowing entity and intra-group equity investments should be value adding, that is, earn a return on capital that exceeds the cost.

Transparency: Disentangling cross holdings and restricting nitric will be a big step towards making the financial statements of the Tata companies more informative.

Some of these changes can (and should) happen soon, some may take a while to unfold but they have to be set in motion, with the recognition that the end game may be that some Tata companies, some with storied histories, may have to shrink or even disappear and that others will be elevated.

Lessons For India Inc

For most of the last two decades, the lament in India is that China has beaten it handily in the global growth game. While it would be unfair to blame this on family group businesses, it is worth noting that the one sector where India seems to have moved forward the most is technology and where it has fallen behind the most is in infrastructure and manufacturing. It may be a coincidence that technology is the sector where, TCS notwithstanding, you have seen the most entrepreneurial activity and that traditional manufacturing is dominated by family group businesses. As India moves towards being a global player, opening up hitherto unopened sectors (like retail and financial services) to global players, the family group structures in these sectors may operate as handicaps. While I don’t believe that it is the government’s place to insert itself within family groups, it should stop tilting the playing field in their favour by doing the following:

Reduce the need for connections to do business: At the core of connection-driven business success is the existence of licences and bureaucratic rules governing businesses. Reducing the licensing needs and the rules that govern how you run businesses will create a fairer business environment, though that may sometimes require governments to accept the result that a foreign company will win at the expense of a domestic competition

Government-based or influenced investors (LIC) should be more activist: The largest stockholder in the Tata Group is the Life Insurance Corporation (LIC), a state-owned company, that has holdings in almost every large Indian company. For decades, LIC has chosen to back incumbent managers against activist investors and has allowed the woeful corporate governance at many family group companies to continue without a push back.

Banking/family group nexus: Bankers, many government picked and influenced, have historically had cozy relationships with family group companies, lending money on projects with little oversight and often with implicit backing from the family group (rather than the company that is getting the loan). Those relationships not only give family group companies an advantage but are bad for banking health and need to be examined.

Conclusion

The turmoil at the Tata Group has all the makings of a soap opera and can be great entertainment if you are an armchair observer with no money in Tata company shares. It would be a mistake, though, to view this as an aberration because the palace intrigue and the infighting that you observe can not only happen in other family groups but take an even darker tone. To the extent that family group companies pushed their companies into public markets because they wanted to raise fresh capital and monetise their ownership stakes, they have to play by the rules of the game

Aswath Damodaran in an academician and management expert who is currently a professor of finance at the NYU Stern School of Business.

This column was originally published on his blog Musings on Market.

The views expressed here are those of the author’s and do not necessarily represent the views of Bloomberg Quint or its editorial team.