Two phases of India's general elections are over and the opportunities for misinformation and disinformation are larger than ever, thanks to artificial intelligence.

On March 16, when the Election Commission of India announced the dates for the general elections, it highlighted misinformation as one of the challenges that it seeks to address.

It's becoming harder for the electorate, civil society, journalists and even governments to combat fake news. A common technology seems to be emerging from conversations this reporter had with policy consultants and journalists: AI-generated deepfakes.

For somebody to create a deepfake, they'd have to use one of several AI video tools available online. These tools are often created off large-scale neural networks that are trained on millions of data points. As a result of this “training”, neural networks are able to create hyper-realistic images or videos based on specific prompts that are input by the user of a tool. These hyper-realistic reproductions that have been created are called deepfakes.

Flashpoint

In November 2023, a deepfake of actress Rashmika Mandanna was created and posted online. In the video, the actress' face was morphed onto the body of a British-Indian influencer. The video went viral, with Mandanna putting out a statement on Nov. 6. The same day, Union Minister Rajeev Chandrasekhar issued a warning on social media platform X (formerly Twitter) referencing the IT Rules, which were notified in April last year.

The Delhi Police filed a first information report, leading to the arrest of a digital marketer from Andhra Pradesh in January this year.

Screengrabs of the original image next to the deepfake video. (Source: @AbhishekSay/X)

The incident sparked a discourse across the government, civil society groups and news organisations regarding concerns about deepfakes and the pitfalls of generative AI.

“That one incident with Rashmika Mandanna kicked off dialogue in the country about deepfakes and its uses in the country,” Siddarth Deb, manager-public policy at TQH Consulting, told NDTV Profit.

What Do Regulations Say?

Union Minister of Electronics and Information Technology Ashwini Vaishnaw in November last year suggested that legislation regarding deepfakes be drafted within 10 days, following consultations with AI experts and National Association of Software and Service Companies.

In the following month, Chandrasekhar said the government was planning an advisory to AI companies instead of draft legislation targeting deepfakes.

Then, in January, several news outlets reported the ministry was considering adding provisions regarding deepfakes into the IT Rules, 2021. However, the latest iteration from April 2023 makes no mention of the term.

What isn't clear is why the government chose to issue an advisory to AI companies, instead of moving forward with drafting legislation, despite a minister's announcement.

Cut to March 1, when the government released an advisory, mandating intermediaries and platforms to seek government approval before the deployment of AI models deemed “under tested” or “unreliable”. This was amended on March 15, with the government ban being lifted and a shift in focus to expectations of transparency, content moderation and tagging of AI-generated content.

But civil society groups like the Internet Freedom Foundation say the government's response to deepfakes has been rushed.

“The kind of consultations they had were a few closed-door interactions with platforms and some AI experts. Civil society members, researchers and journalists weren't present. It's led to these hurried policy interventions,” Tejasi Panjiar, associate policy counsel at the foundation, said. “It has been entirely reactive."

Archis Chowdhury, senior correspondent at Boom, a fact-checking platform, concurred. “We don't know on what basis is regulation being built,” he said. “They're not taking any suggestions from civil bodies and stakeholders who might have some legitimate suggestions regarding improving them."

Deepfakes should be a concern for India, elections or not, because of the nation's low digital literacy. Only about 38% of households in India are digitally literate, according to the Dattopant Thengadi National Board for Workers Education and Development. The percentage in urban households is at 61%, as compared with 25% in rural areas.

In February, the IFF had, in an open letter, urged political parties to promise not to misuse AI-generated content, so that the elections remain free and fair. “There is no transparency, no research, no accountability,” Panjiar said, adding that political parties have in the past reposted AI-generated content from official and party-affiliated social media handles.

Chowdhury has a similar view. “Political parties have a stake in the technology, they're deploying deepfakes and that's why we don't see any transparency from them.”

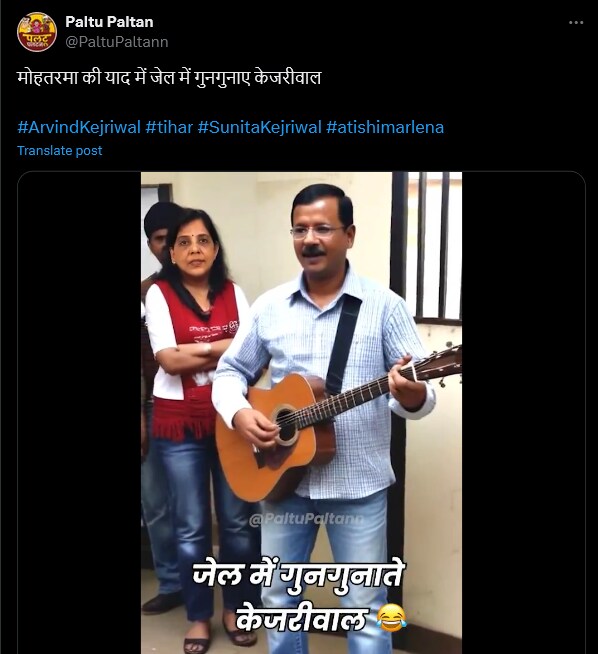

A deepfake of Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal posted online (Source:PaltuPaltann/X)

Are Rules Enough?

Before the announcement of the election dates in March, Meta and Google released their own guidelines on what their companies were going to do to minimise fake news, flag inaccurate information and identify AI-generated content. Social media platform X hasn't released dedicated guidelines but their FAQs mention that the site cannot be used to post or share misleading content regarding elections.

The ECI, in a section on its website titled “Myth Vs Reality”, addresses instances of fake, misleading or false news and provides correct data. So far, it has corrected instances of inaccurate information from TV channels, newspapers and even magazines, all of which are displayed on the website. The corrections are only available in English and not in Hindi or any of the country's several languages.

The Election Commission and social media companies need to invest in developing digital media literacy, especially outside of major cities. “There needs to be some sort of inoculation so that people can tell what is digitally altered content and what is real,” Deb said. “That's going to be a huge challenge over the next two to three months.”

Voter outreach programmes as well as educating people about what deepfakes are and the danger they pose seem to be the need of the hour. “This is an inflection point; there could be a lot of damage done because a lot of people are not aware of this technology and might be seeing such things for the first time,” Chowdhury said.

As far as legislation is concerned, the government needs to have a fixed understanding and definition of online harms, according to Panjiar. “Once they have that understanding and have taken into consideration the views of civil society, news organisations and factcheckers, then they should move ahead with thinking about introducing regulation,” she said.

Authentication Protocols

Deepfakes are the very reason why experts have been pushing for the C2PA Specifications for Content Credentials to be adopted by organisations across the world. C2PA authentication works on “provenance”, which refers to the historical facts of a digital asset, i.e. metadata. Content credentials help authors bind their unique credentials to sets of “provenance data”.

For example: Someone sends you a video containing several controversial allegations. To verify whether the video is fake or real, you can check whether it has content credentials via an enabled application.

However, one of the main issues surrounding the use of C2PA is that just because content doesn't have this set of authentication factors, need not mean it is fake or manufactured. And therein lies the issue.

“Identification itself is a challenge whether something is real or generated by AI,” said Deb. “It remains to be seen to what extent content watermarking and AI watermarking can be helpful.” Part of the reason, he explains, is because while the technology is promising, it's not fool-proof as it is still experimental and prone to circumvention.

While news organisations like Boom use an AI detection tool like Itisaar, a deepfake detection service developed at IIT Jodhpur, they're facing a similar problem. “Detection tools are very expensive and their deepfake detection accuracy is quite low, at around 70%,” Chowdhury said.

The problem, he said, stems from the fact that everybody is falling behind on detecting deepfakes, while creating such content is really cheap.

Essential Business Intelligence, Continuous LIVE TV, Sharp Market Insights, Practical Personal Finance Advice and Latest Stories — On NDTV Profit.