India is on the cusp of banning single-use plastics. Yet, a blanket ban cannot be the only way to curb pollution from the non-biodegradable material that lasts for centuries.

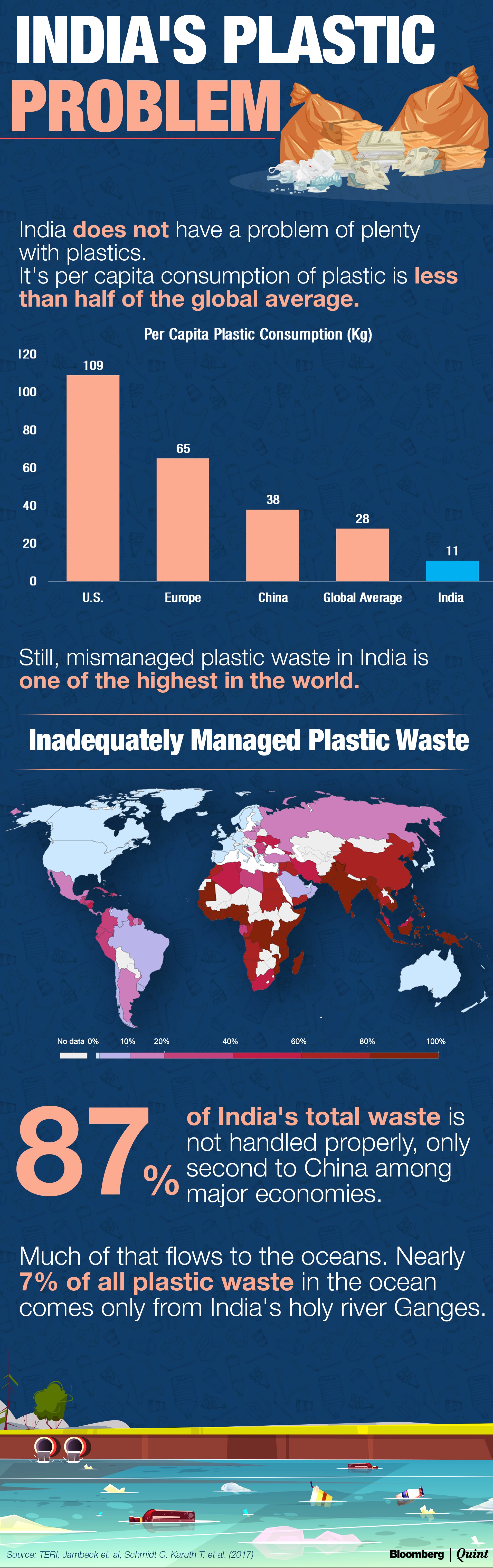

Every day, India generates plastic waste that weighs as much as 150 large blue whales—the biggest animal known to exist. The problem though is not the volume of plastic waste it generates but the disposal of it. An average Indian consumes almost ten times less plastic than an average American. According to The Energy and Resources Institute, India's per capita consumption of plastic is less than half of the global average.

But when it comes to handling waste, India fails miserably. The country's pollution board estimates that India generates about 26,000 tonne of plastic waste every day. But over 10,000 tonne remain uncollected.

Almost 90 percent of waste generated in India is mismanaged, according to a study on plastics published in Science journal.

A lot of it includes plastics. Bulk of that is dumped into rivers and then flows into the ocean, polluting the waters and damaging the marine ecosystem. The rest is burned out in open dumps and landfills.

Perhaps why India has joined the global backlash against plastic, the ubiquitous material that humans can't seem to do without. According to the United Nations, at least 127 countries have placed some form of regulations on single-use plastics. The call to shun the material is such that “single-use” became the Collins Dictionary's word of the year in 2018. The word, according to them, has seen a four-fold increase since 2013.

That's not without reason.

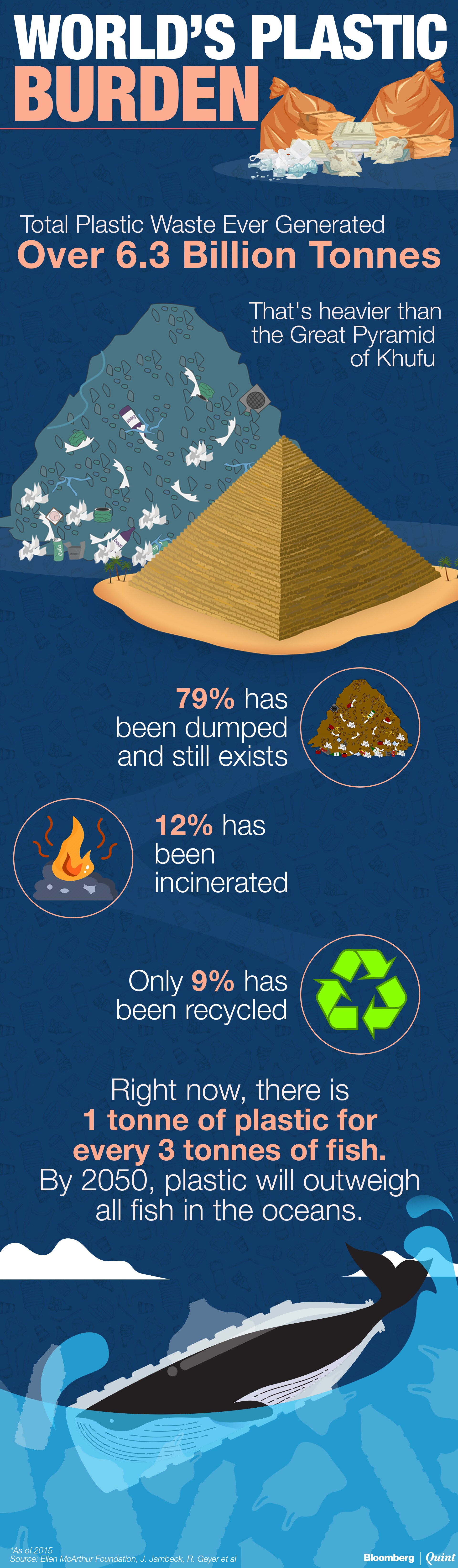

6.3-Billion Tonne Problem

Over 6.3 billion tonne of plastic waste has been generated in the world so far, according to a study by Britain's Ellen McArthur Foundation. That's equivalent to the average weight of more than 1 billion African bush elephants. Around 90 percent of this plastic will not decompose for at least 500 years—polluting food, water and air.

There's more to plastics than its health hazard to humans and animals alike. Every year, according to Trucost, a research arm of Standard & Poor's, it costs nearly $75 billion in environmental damages.

But Alternatives Are Limited

Humans need plastic for just about everything. Replacing it is not easy. And it also has a problem: alternatives to plastic, a separate study by Trucost found, would quadruple the environmental costs by increasing the carbon footprint.

And Danish researchers realised it when they compared plastic bags to other alternatives. Take cotton bags for instance. Factoring in the water and energy used in production, you'd have to reuse a single cotton bag more than 7,000 times to have the same environmental impact as a polythene bag, according to a study by the Denmark's environment protection agency. The study does not account for the fact that a cotton tote will biodegrade within 5 months while plastic would take centuries.

This, too, becomes relevant for India. If the country's waste handling and recycling mechanism is weak, and it bans plastics completely, then it will end up replacing it with much more environmentally costlier alternatives.

Are Bans Futile?

No. At least that's what the United Nations Environment Programme report suggests. But plastic bans will be effective only if there's a concerted effort by the policymakers and the public at large.

India has not specified how it plans to implement a ban. Prime Minister Narendra Modi urged citizens on Aug. 15 to stop using single-use plastics. Since then, a number of government ministries and state-run companies have replaced single-use plastics.

No road map, however, has been notified yet. An announcement is expected on Oct. 2, Mahatma Gandhi's birth anniversary. The country's Central Pollution Control Board has considered various ways of reusing plastic from laying roads to generating energy.

But policymakers could do well to heed the advice of former chief of UN Environment before making plans:

Plastic isn't the problem. It's what we do with it. And that means the onus is on us to be far smarter in how we use this miracle material.Erik Solheim, former executive director, UNEP

Essential Business Intelligence, Continuous LIVE TV, Sharp Market Insights, Practical Personal Finance Advice and Latest Stories — On NDTV Profit.