Some of India's largest firms have announced net-zero goals as companies globally switch to sustainable investments and seek suppliers with similar commitments to curb greenhouse emissions.

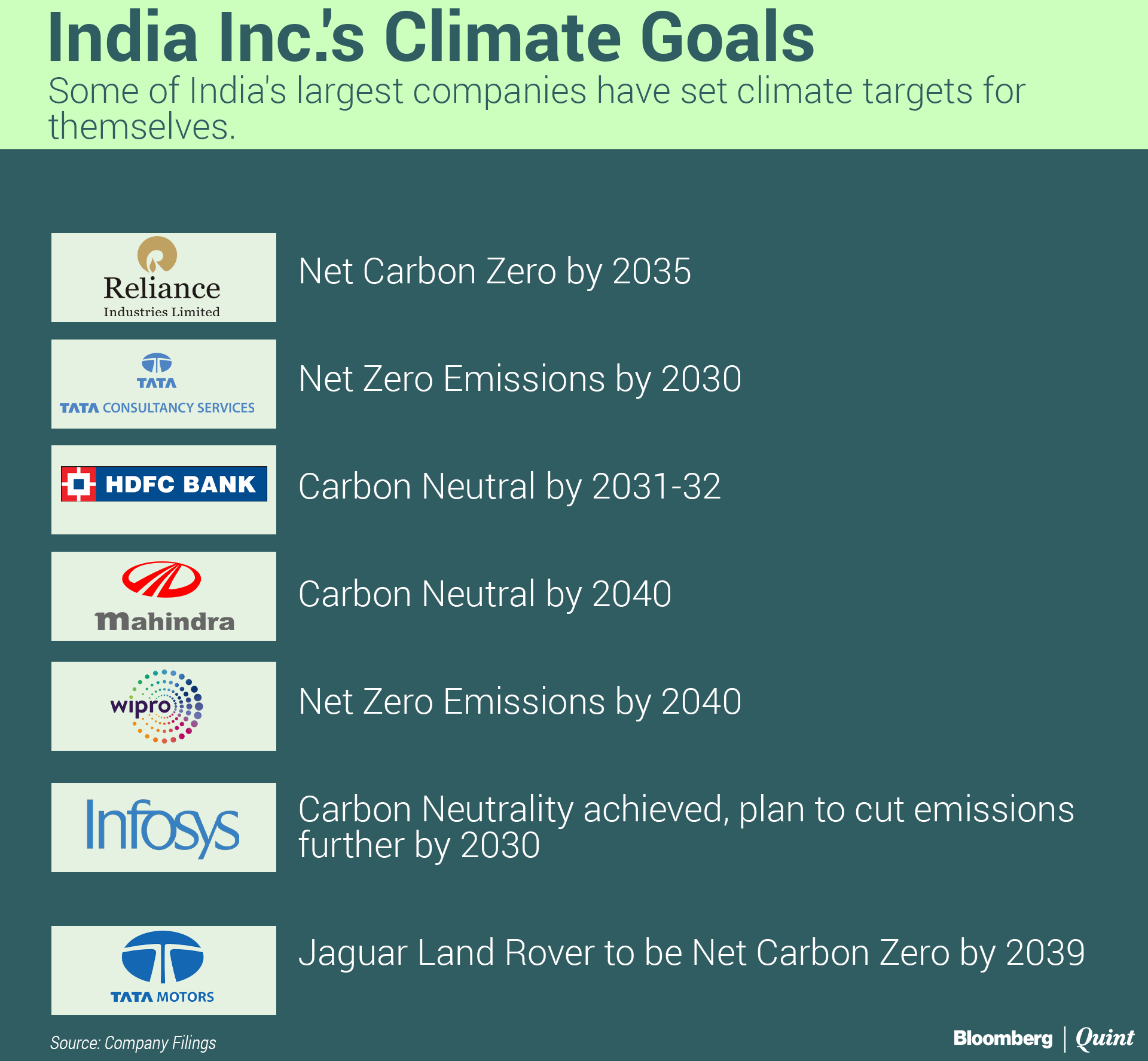

Mukesh Ambani's oil-to-telecom conglomerate Reliance Industries Ltd. said it will turn "net carbon zero" by 2035. Private lender HDFC Bank Ltd. has set 2031-32 target for being carbon neutral, while Tata Consultancy Services Ltd. seeks to be there by 2030. Wipro Ltd., Infosys Ltd., Mahindra & Mahindra Ltd., JSW Energy Ltd. and even Indian Railways have also announced similar plans.

And these are not the only ones. As many as 56 Indian companies have committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions, according to the Science-Based Target Initiative, a global coalition that enables firms to set climate goals.

Customers, investors, lenders, business partners, regulators, governments and citizens—they're all pushing companies towards environment and social corporate governance.

BloombergQuint deconstructs “net-zero” and explains what Indian companies seek to achieve.

What Is Net-Zero?

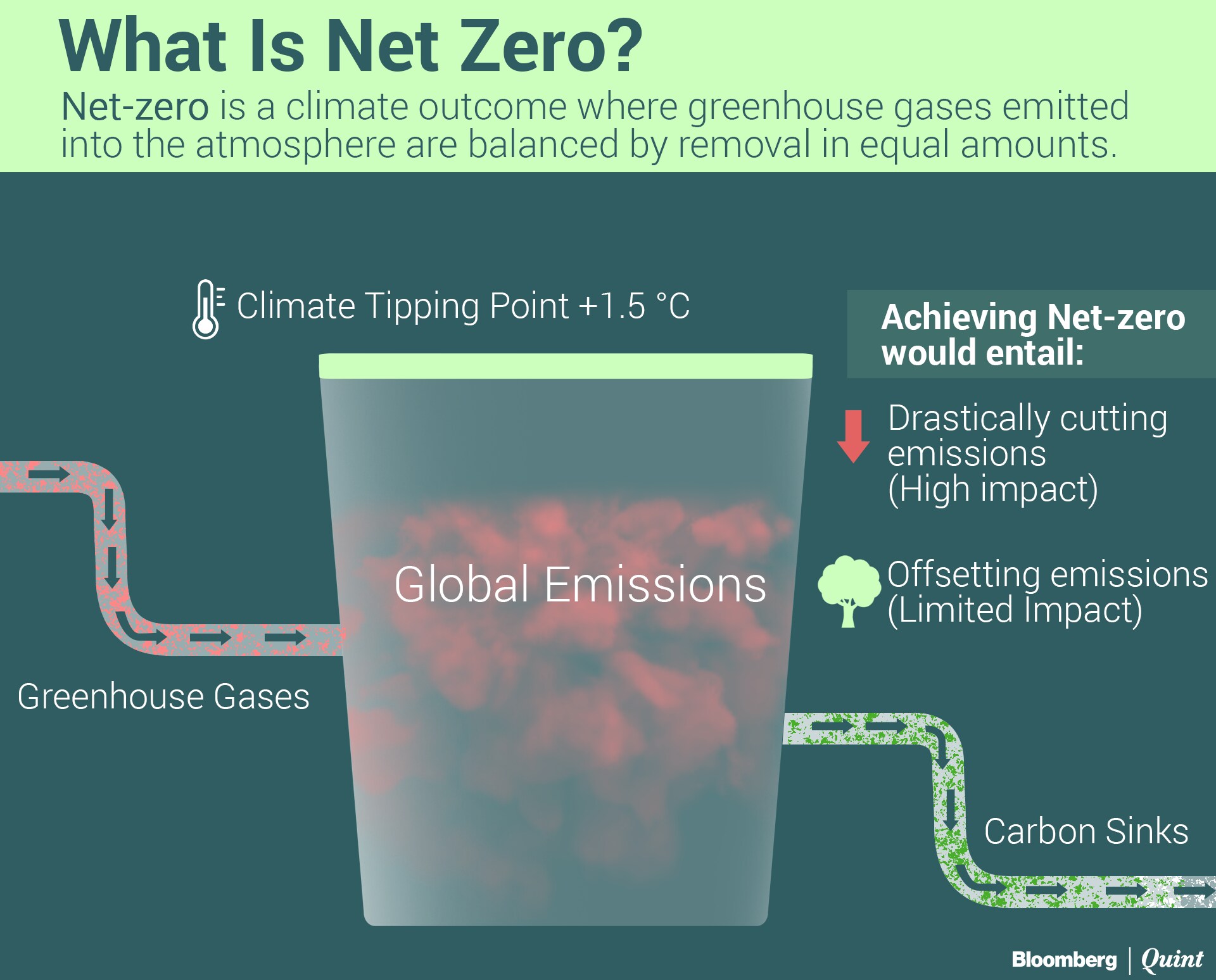

Net-zero is a climate outcome where any greenhouse emissions through man-made sources are countered by removing such gases in equal amount. The 'net' effect is that the global temperature remains unchanged.

There are two ways to achieve this: drastically reduce emissions and simultaneously use methods to neutralise or remove greenhouse gases.

And why's it relevant? Foremost is to avoid an impending climate catastrophe.

Vaibhav Chaturvedi, the lead for low-carbon pathway research at the Council on Energy, Environment and Water, explains. Consider carbon budget—the maximum limit of emissions that the Earth can handle before heating up. If we continue to release emissions on a net basis, that budget is breached and temperature continues to rise.

“Think of it as a water tank that is filled three-fourths. And a stream is connected to the tank that constantly keeps filling it,” Chaturvedi said. “The idea is that we reduce the flow of the stream so that the water doesn't start to overflow.”

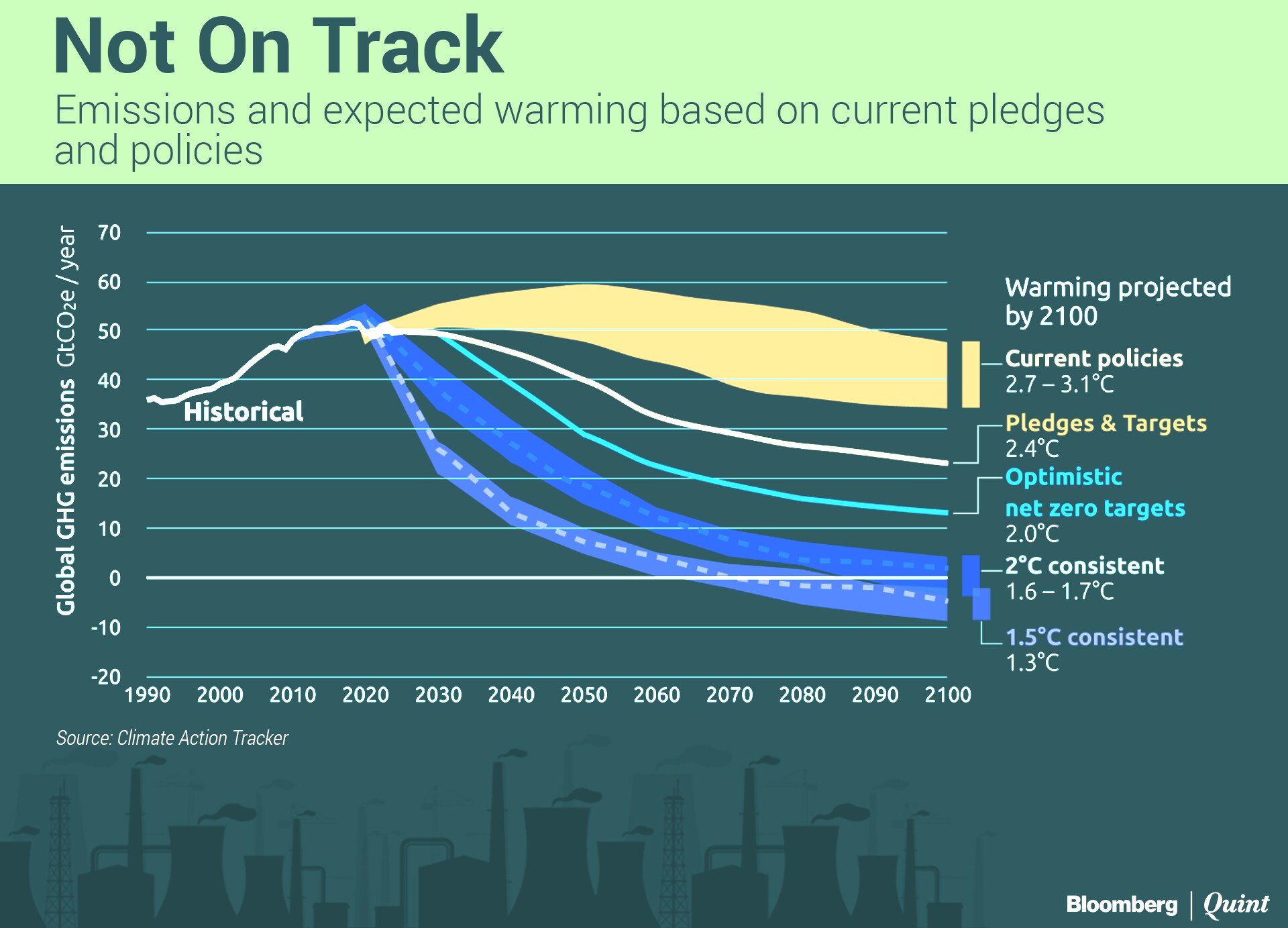

Policymakers across the globe have a consensus that setting net-zero goals is a plausible way to contain further damage and, hopefully, reverse some of it. Under the landmark 2016 Paris climate agreement, countries including India agreed to limit global warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius, ideally 1.5 degrees C. A special report by nearly 100 scientists found that to achieve the goal, the world would have to hit net-zero emissions by 2050. That's not likely given the current progress.

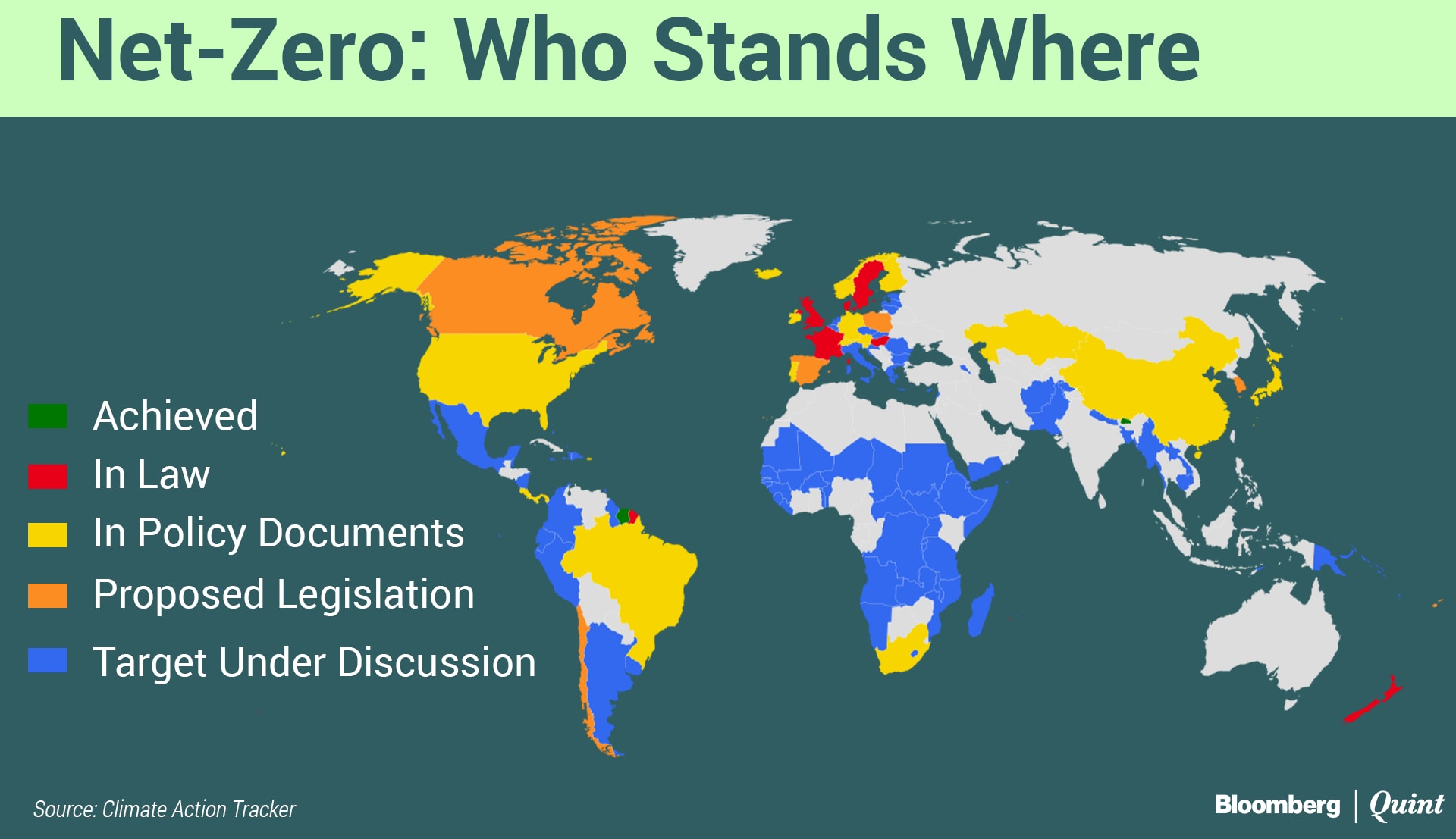

Developed nations such as the U.K., France and Denmark, with higher emissions, have already codified in law their commitment to net-zero by 2050, according to the Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit. The European Union, South Korea and Canada have also proposed similar legislation. The U.S., Japan and Germany are considering making it a law.

India, a developing nation with relatively lower per capita emissions, doesn't have a net-zero target. But authorities are said to be considering pledging to net-zero by 2050

Why Should Companies Care?

Bulk of the emissions come from industries—particularly in the energy, metals and transportation sectors. Any climate action will have to start by reducing or offsetting emissions that come from the industrial and commercial activity.

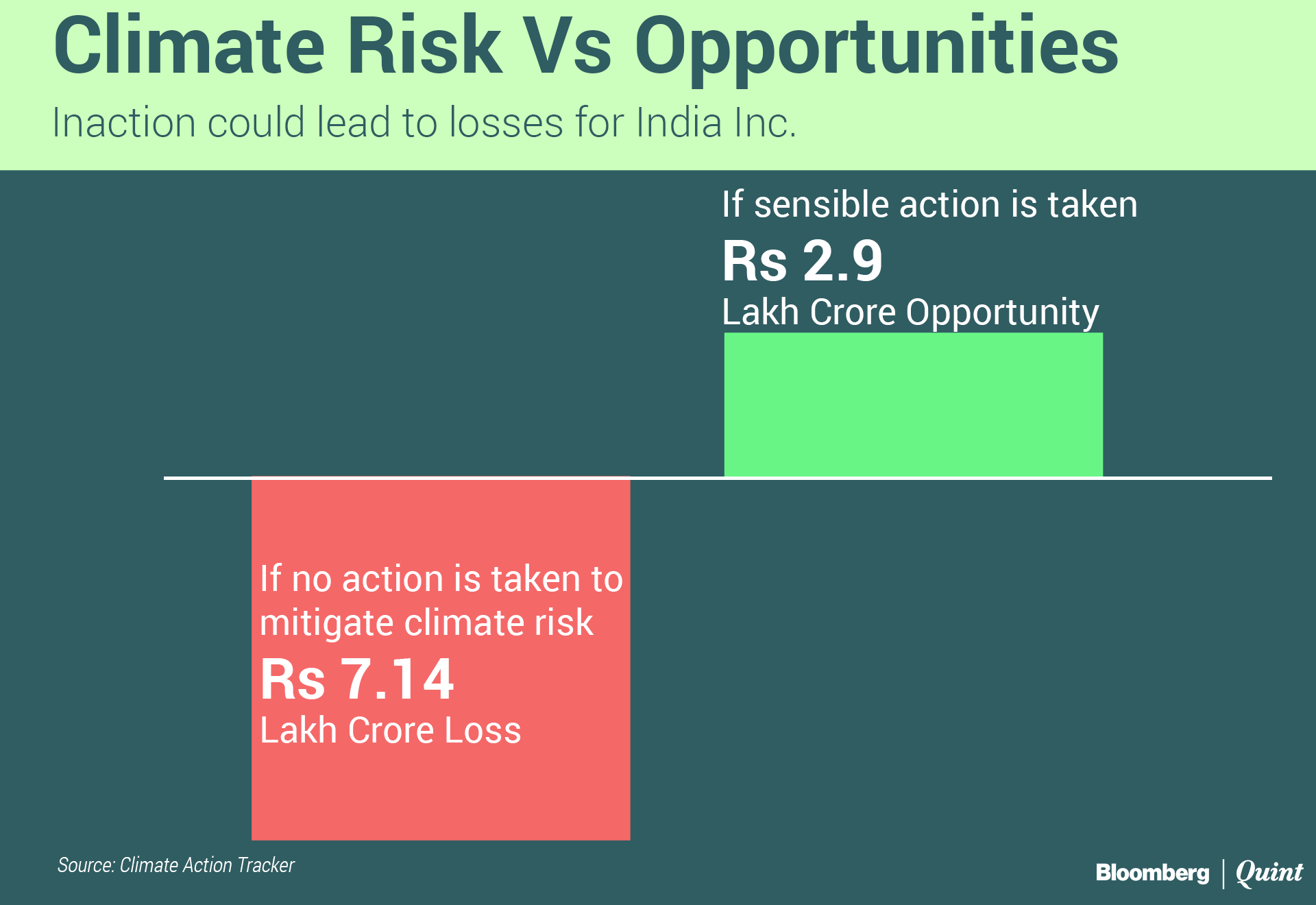

There is also the need to negate potential business losses. According to the Carbon Disclosure Project, Indian companies stand to collectively lose over Rs 7.14 lakh crore if they do nothing to mitigate climate risks in the next five years. These risks come from physical phenomena like floods, emerging regulations, emission caps, changing customer behaviour and preferences, and even potential legal issues. But if done right, opportunities worth Rs 2.9 lakh crore could emerge.

Indian suppliers of multinational firms also risk losing $274 billion worth of exports every year if they fail to curb carbon emissions, according to Standard Chartered.

Firms in the developed nations are already preparing for it. A recent report by the ECIU showed that a fifth of the world's largest companies have committed to the net zero target.

Besides, socially responsible investing is on the rise and investor money is increasingly coming with explicit climate-related goals. Investments with ESG commitments have now crossed $40 trillion globally, according to ESG Risk. In India, 7% of the assets under management are ESG investments. That number likely to rise to 30% by 2030.

“A large chunk of the global investors want to put their wallet behind projects that help curb environmental damage,” said Vibhuti Garg, an energy economist and India Lead at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. “An increasing amount of money is now going into stock mutual and exchange-traded funds with environmental goals as part of their mandates.”

And that money from investors is getting hard to come by for companies in polluting industries. “Banks and financial institutions with large funding portfolio to fossil fuel assets, like BlackRock, JPMorgan Chase, Korea Development Bank and the Japan Bank of International Cooperation have announced exit policies from their coal investments,” Garg said.

What Can Companies Do?

Pledging is easy but the road to net-zero will be tricky.

Companies mainly have three types of emissions. There are direct emissions from sources that are owned or controlled by companies—like furnaces, boilers or transportation. There are also indirect emissions from the coal-fired electricity consumed by a company. The third includes all other emissions that occur in the company's value chain.

These three categories are referred to as Scope 1, Scope 2 and Scope 3, respectively.

This makes the transition to net-zero for companies in the services sector relatively easier, since majority of their emissions are from indirect sources, Chaturvedi said. "The only thing they need to do to is to change their energy source to renewables and they will be able to cut most of their emissions."

TCS has a similar plan. It will make more efficient use of energy across its operations, expand use of renewable energy sources and work with its supply chain partners to reduce emissions, the company said. It also plans to rationalise business travel.

HDFC Bank, too, aims to be carbon neutral by sourcing 50% of its electricity from renewable sources and decrease absolute emissions. It aims to reduce water consumption, single-use plastic and plant 25 lakh trees to offset its carbon footprint. The lender also plans to issue green bonds—debt instruments used to fund projects that have a positive impact on climate.

“It's easier for them because doing this doesn't change the fundamentals of their business,” Chaturvedi said.

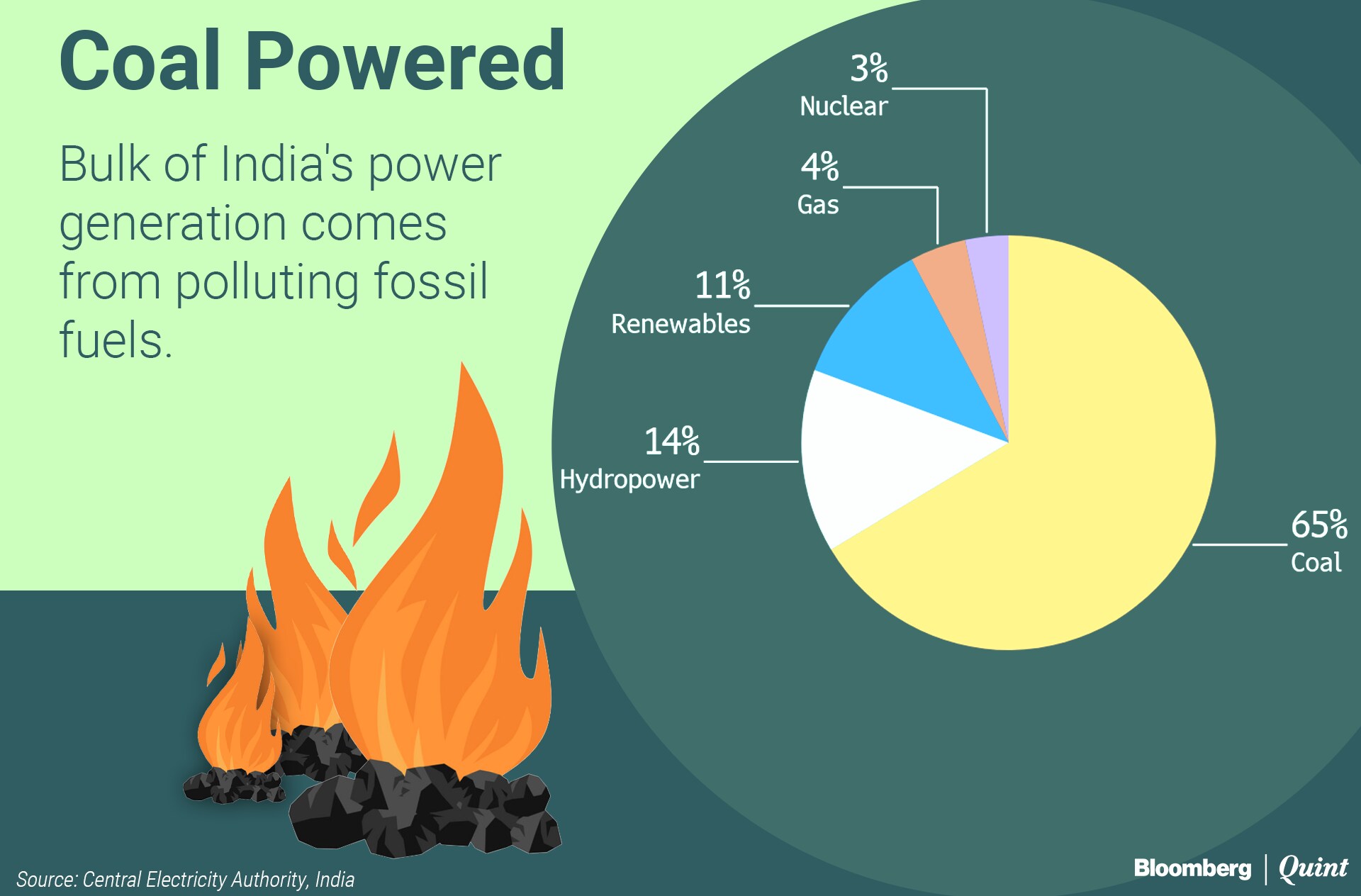

The challenge will be a lot bigger for companies that will have to fundamentally alter their business. The energy sector, for instance, is still largely coal-powered and contributes more than half of India's emissions, Chaturvedi said. “That's why you will see these companies increasing investments in renewable sources. They know the writing on the wall.”

Reliance, even after diversifying into digital and retail, still gets half of its revenue from oil and gas. To meet its net carbon zero target, the Ambani firm said it will use newer technologies to reduce emissions, and plans carbon capture and storage—to convert carbon dioxide into useful products.

RIL also claims it is already sourcing carbon-neutral oil or crude produced with net-zero emissions. And is increasing use of renewable sources of energy to power operations.

Sectors like metals and cements will also find it harder to transition as emissions are an inherent part of the production process. “These are known as hard-to-abate sectors. Unless we have a technological breakthrough, it'll be very hard for a Tata Steel Ltd. to come out and say we are going net-zero,” Chaturvedi said.

Such companies usually introduce a concept of internal carbon pricing to show climate action. That is when a firm puts a price to every unit of carbon that is emitted by them and then uses the proportionate money to fund green investments. Mahindra & Mahindra Ltd. was the first Indian company to set carbon price of $10 per tonne of carbon emissions.

How To Assess Net Zero Pledges

Right now, it is difficult to assess how realistic Indian companies climate goals are in the absence of regulation that makes them target and transparently report specific environmental goals.

Garg said one way is to see the companies' history of clean energy adoption which could reflect their intentions and their ability to go net-zero. “Their ability to access finance to deploy such solutions can be another parameter to assess whether their plans are realistic or not.”

According to Chaturvedi, government regulations would also help. “The moment India says it wants to go net zero, it means the companies would no longer have an option to not pursue it,” Chaturvedi said. “Many of us argue that this voluntary establishing of goals by companies is good, but it cannot lead us to deep decarbonisation.”

CEEW has said that India should set a long-term target of achieving net-zero by 2070. A 2050 target may not be very feasible for the country to achieve given its vast dependence on dirtier fuels.

“Ambiguity is never good for business. Right now, with no targets, companies also don't know what a right timeline for transition is. The moment government says our net-zero target is 2070, that will be a credible deadline for the companies,” Chaturvedi said. “And 50 years is a long enough time for firms to chart out their transition and execute it.”

Essential Business Intelligence, Continuous LIVE TV, Sharp Market Insights, Practical Personal Finance Advice and Latest Stories — On NDTV Profit.